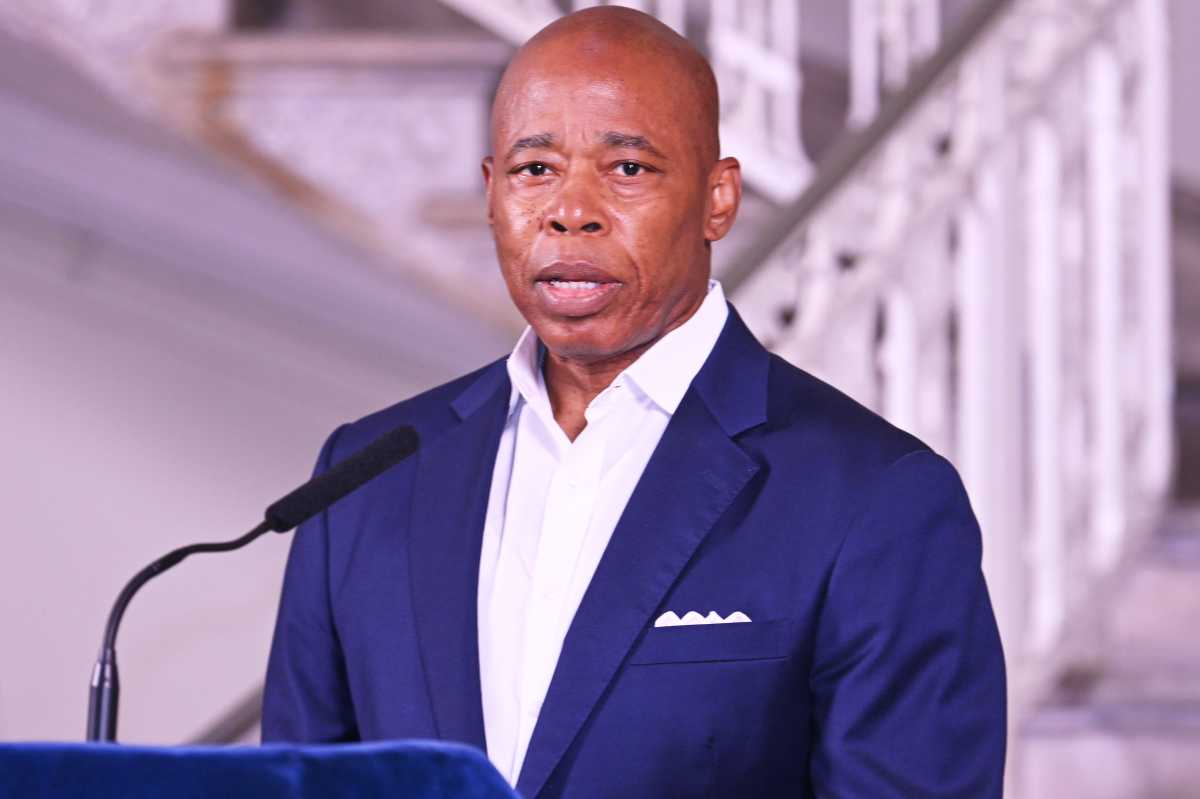

Hollywood hasn’t called Roberta Davenport yet, but the life story of this principal of Vinegar Hill’s PS 307 reads like one of those inspirational screenplays: She grew up in the Farragut Houses only to return to her old neighborhood in 2003 to take over a school suffering from low attendance, rampant disciplinary problems, and abysmal test scores. Now, the elementary school is known for its art programs and its nationally competitive chess team, and academic performance is on the rise. She checked in with Harry Cheadle to talk about coming back to the old neighborhood.

Q: You grew up in the neighborhood where you’re now the principal. How has it changed since you were a child?

A: My family was one of the first families to come into the Farragut Houses, back in 1952. My dad worked as a plumber in Brooklyn Navy Yard. Every afternoon at 4:15, the whistle would blow, and you’d see a stream of workers coming home from the Yards. It was almost idyllic, a mix of families from different ethnic groups: you had Irish, Italians, blacks who had just come from the south. It was beautiful, clean, safe. We’d leave our doors open. Everyone looked out for everyone else.

Q: So what happened?

A: I left in the 1980s, when drugs came into the area in a very terrible way. It touched everyone. I had a wonderful experience in the Farragut houses. The children of today have a very different experience.

Q: So when you got back to PS 307, what was the situation there?

A: It was a fragile school. Its academic performance was so poor that the state had taken it over. What I had to do was look at what was influencing the performance. Attendance was too low. We wanted to look at the facilities and make sure the school was safe, child-friendly and orderly. That summer, we had a devastating break-in that just affirmed we had to build a community school, a school that the community was invested in.

Q: How do you build a “community school?”

A: We had to be very clear with everyone what our values were. The parents had to know the expectations were clear. The bottom line for our children was there were certain expectations for what you could do in school and what you couldn’t do. Boys and girls, you must come to school on time, prepared and appropriately dressed. Everyone has the right to be in school to learn and no one has the right to stop that. School should be considered sacred time. That meant fighting had to go out the window. We had zero tolerance for aggressive behavior. We had to look at bullies, make sure they were identified and dealt with.

Q: You also started a lot of after-school programs. How did that work out?

A: One of the first collaborations was with the Brooklyn Ballet, and some of our children realized they have a love of dance and received dance scholarships. I also brought in Chess in the Schools, and it’s incredible what has happened in two years: our children took second place in the national championship and first place in Brooklyn this year. The kind of recognition that our children had not been receiving is coming now, and that transforms them. When we believe in children and set high expectations, our children expect success. For too long, PS 307 had been neglected. We seem to be under the radar. There’s great potential here.

Q: But there’s more work to do, right?

A: Yes. I want to improve academic performance and get 70 percent of the students reading at grade level. It’s only 40 percent now.

Q: Ouch. Is that the most problematic area for the school?

A: Yes. We’re making some instructional changes. We’ll be ready this year.

Q: What was most difficult thing you’ve had to do so far as principal?

A: I think to really get in people’s hearts and minds, the idea that this is not my school; it’s the children’s school. I talk to the children, ask, “How can we make this school better, boys and girls?”