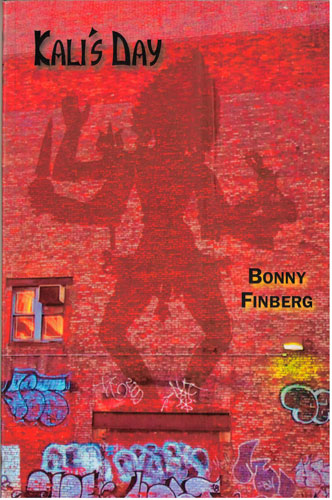

“Kali’s Day” by Bonny Finberg is a recent and rare dip into narrative fiction from Williamsburg’s storied post-structuralist publisher, Autonomedia. It will primarily appeal to those who like the theme of a jaded Westerner finding her true self in the mystic squalor of the Far East.

The novel is a series of voice pieces narrated by different members of a modern family in pre-Giuliani Manhattan. One is a dope addict, one an alcoholic pot dealer, one addicted to the love of the pot dealer, and one a teenager relegated to the care of these “adults.” Stella, the fifteen-year-old, is by far the most sympathetic character — certainly the least narcissistic.

Though it is set in the pay-phone era, the thematic composition is smartphone selfie. Each first-person narrator fills the frame, allowing us only glimpses of setting or plot behind them. Finberg renders the milieu of un-policed parks, dive bars, and diners charming, but we are largely confined to the characters’ emotional priorities.

Like teenage Stella, shunted around willy-nilly by self-involved older people, we the readership have no say in whose first-person care we are consigned to. One is most aware of this during passages narrated by Henry, an obsessive Othello with apparently nothing on any given day’s to-do list except eternally endeavoring for exclusive sexual ownership of the also unpleasant, tantrum-throwing alcoholic Candice. Candice is mercurial and sloppy, Henry dog-loyal, jealous, accusatory, as relentless as a swarm of mosquitoes. Their unhealthy love affair is adolescent, in both its histrionic intensity and the disproportionate percentage of their attention it occupies.

Beyond Henry’s paranoid pursuit of control over Candice, characters’ goals are rarely clear. Contributing to the sense of this being a sitcom is that no one seems concerned with money: they’re able to secure hotels, international plane tickets, taxis and restaurant meals at a whim. The cast’s total detachment from materialism or money worries — particularly refreshing considering their involvement in the drug trade — is perhaps a sign of how well-suited they are for the book’s second half, which relocates them all to Nepal.

A lot of this book is what the characters feel, and a lot of what they feel in Nepal is spiritual awe. If you share their outlook, you’ve hit an emotio-religious jackpot. If, on the other hand, you’re the kind of ugly cynic who scoffs at the wonderment tourists experience taking part in exotic rituals, you can only bide your time. Wherever these characters go, there they are. Strikers shut down the road to the airport, and none of our narrators express any curiosity towards what the strike might be about or why it’s happening — all that matters is whether it will delay Henry meeting Candice’s transatlantic flight. The approach to spirituality is similar: what can this offer me?

The Nepalese setting is interesting. After an unusually long single-character sojourn, the book dissolves into a series of quick-cuts, ending in montage. Those who cling to a Western sensibility in which goal or destination matters will be duly chastened, left to reflect on the journey itself.