Last year, a divergent group of art scholars,

constitutional lawyers and cultural critics met in Chicago for

a nine-hour arts symposium with the charged title: "Taking

Funds, Giving Offense, Making Money."

The audience of nearly 400 argued over the latest event in America’s

cultural wars – the fight between the Brooklyn Museum of Art

and Mayor Rudolph Giuliani over "Sensation: Young British

Artists from the Saatchi Collection" (Oct. 2, 1999 to Jan.

9, 2000).

They must have gained some perspective in Chicago, far from the

hype and hysteria in New York, because the book that resulted

from the symposium presentations – "Unsettling Sensation:

Arts-Policy Lessons from the Brooklyn Museum of Art Controversy"

(Rutgers University Press, $25) – finally provides a nuanced

account of what happened during the tug-of-war over artist Chris

Ofili’s painting, "The Holy Virgin Mary," in Brooklyn

in the fall of 1999.

The 21 essays in "Unsettling Sensation" respond to

the controversy along a number of sightlines including the law,

the public’s relationship to museums, offensive images, government

funding and the press.

The "Sensation" exhibit was supposed to bring a young,

hip audience that cared about art but knew next to nothing about

the art museum in Brooklyn, according to the book.

It worked.

The 9,000 visitors who attended opening day, some waiting as

long as 90 minutes for one of the $9.75 tickets, doubled the

museum’s previous one-day record for "Monet and the Mediterranean"

set on Jan. 3, 1998. Brooklyn Museum of Art director Arnold Lehman,

in fact, had already doubled the museum’s annual attendance from

250,000 in 1996 to 470,000 in 1999.

But even as "Sensation" brought a new audience to the

Brooklyn Museum, it raised questions about the government’s right

(or lack thereof) to determine the content of the cultural institutions

it funds and the future of museums’ relationships with their

donors and audiences.

Legal battle

The First Amendment question, as demonstrated by five of the

essays in "Unsettling Sensation," is still far from

settled. The mayor withheld the Brooklyn Museum’s funding because

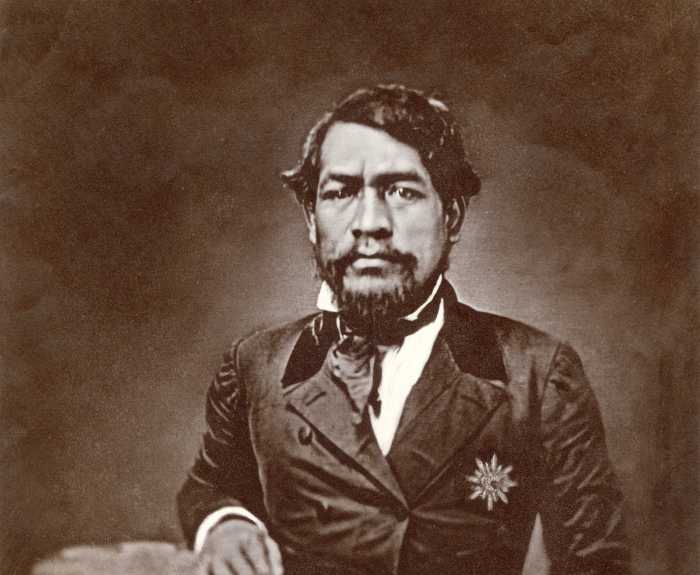

he objected to Chris Ofili’s painting (see photo at left). Giuliani

then tried to evict the museum; the museum sued the mayor on

First Amendment grounds and won before federal Judge Nina Gershon.

According to the law professors writing in "Unsettling Sensation,"

the case was not the black-and-white issue it was popularly believed

to be.

At the time, the city provided about $7 million of the museum’s

annual $23 million budget. Those numbers roughly hold today.

In his essay "The False Promise of the First Amendment,"

University of Chicago law professor David Strauss theorizes that

it may have been a Pyrrhic victory. If enough judges take the

same road as Gershon and come down emphatically on the side of

public art institutions against their government benefactors,

"governments would begin to ask themselves exactly what

they are getting themselves in for if they fund this exhibit,

this group of performers, or these artists." After all,

government is not constitutionally required to fund the arts.

Strauss’ underlying argument, which he shares with Stephen Presser,

a professor of legal history at Northwestern Law School, is that

the museum’s victory was far from assured. If it plays its cards

right, the government does not have to fund offensive material.

Presser writes that Giuliani should have been able to sever the

city’s partnership with the museum on the grounds that the museum

violated that partnership. The city, represented by corporation

counsel Michael Hess, raised this issue to no avail.

The mayor assured his own defeat by attacking the museum too

strongly. Had he tried to use a more delicate method of withholding

funds he might have had a legal leg upon which to stand.

Then again, Giuliani appeared less worried about removing Ofili’s

painting from the exhibition than making political points with

upstate Conservatives (to shore up his campaign for a Senate

seat) writes David Ross, director of the San Francisco Museum

of Art. If Giuliani’s role as the strident moral opponent was

"scripted," so was that of Lehman, as the promoter

of the show.

Being ’hip’

Narrowed to its component parts, Ofili’s "The Holy Virgin

Mary" is paper collage, oil paint, glitter, polyester resin,

map pins and elephant dung on linen. In a broader context it

was part of a provocative appeal to younger audiences. When the

museum began to print tongue-in-cheek advertisements warning

that the exhibit might induce nausea or vomiting the point was

clear: This is not your parent’s Brooklyn Museum of Art.

"We have a vast community of people for whom we’re not relevant,"

Lehman said in an interview last year. "We have to figure

out how we can become increasingly significant in people’s lives.

We can’t do it by insisting that they learn about Renaissance

art."

His words just as easily apply to the Brooklyn Museum’s subsequent

exhibit, "Hip-Hop: Roots, Rhymes and Rage" (Sept. 22

to Dec. 31, 2000), an attempt to attract younger black and Hispanic

audiences and any youth who like hip-hop music and culture. The

words also apply to the upcoming "Star Wars: The Magic of

Myth" exhibit (opening April 5, 2002) and to any of the

record-breaking exhibits at Manhattan’s Guggenheim Museum, like

"Armani" (Oct. 20, 1999-January 17, 2000) or "Art

of the Motorcycle" (June 26, 1998-Sept. 20, 1998) that,

at least on the surface, appear more market driven than educational.

Such exhibits, it can be argued, seek to broaden and democratize

a museum’s audience. At the same time, the broader demographics

make the museum more appealing to corporate donors. There is

no reason why a museum can’t satisfy its personal needs while

meeting the public’s.

"Our audience today reflects in part a responsiveness to

that exhibition [Sensation] in terms of the museum having a younger,

somewhat diverse and increasingly committed audience," Lehman

told GO Brooklyn.

Dwindling funds

The needs of these institutions have grown, however. Corporate

and government funding for public museums has dropped dramatically

in recent years. In the year "Sensation" opened, the

Alliance for the Arts, which tracks New York City’s arts organizations,

released a report on funding for non-profit arts organizations.

In New York City, federal arts funding nose-dived by 88 percent

to cover just 1.2 percent of arts organizations’ budgets, according

to the report. In that same period New York City cut funding

to non-profit cultural institutions by half. Corporate funding

dropped in those years from 5.6 to 3.9 percent of the New York

arts organizations’ budgets.

No surprise then that some museum directors were running scared.

"The ’greater’ scandal of the ’Sensation’ show was that

it revealed (oh marvelous revelation!) that art museums are in

competition with movies, shopping malls and theme parks,"

writes W.J.T. Mitchell, an art history professor at the University

of Chicago, in "Unsettling Sensation."

"Sensation" was funded, in part, with $160,000 from

Charles Saatchi, $50,000 from Christie’s and $75,000 from David

Bowie. It was a four-way relationship. Christie’s stood to gain

from any potential future sale of the art work; Bowie, who recorded

the audio tour that accompanied the exhibit, was given the rights

to use the art on his Web site; and Saatchi, well, Saatchi owned

the art, and had a reputation of buying large quantities of contemporary

art, aggressively promoting it, then turning around to sell it

at a profit.

Mitchell suggests that Brooklyn was only guilty of indiscretion

by hiding Saatchi’s donation, yet museums have long kept their

internal operations cloaked because they are not as pretty as

the objects inside. Artist Hans Haacke managed to offend the

Guggenheim when he attempted to exhibit photos of tenement buildings

owned by the museum’s trustees, Mitchell points out in "Unsettling

Sensation." The incident took place in 1971, and the exhibition

was cancelled six weeks before its scheduled opening. The Guggenheim

fired the show’s curator.

Lehman has said he "begged" Saatchi to fund the exhibit

after corporate sponsors refused to back it and that the secrecy

was due to Saatchi’s desire to remain anonymous.

"To me that means if a reporter asks me about it I’m going

to say ’no,’" Lehman said.

"I tried to convince [Saatchi] to help," Lehman told

GO Brooklyn. "It was never a question of funding the exhibition.

What he did was only a fraction [of the exhibition’s costs]."

The consensus on the Brooklyn Museum’s actions is described in

"Unsettling Sensation" by James Cuno, director of the

Harvard Art Museums, who writes: "In pursuing this exhibition

and its funding as it did, the Brooklyn Museum took chances not

many museum directors would take." Cuno acknowledges that

Harvard has in the past taken donations from the owners of its

exhibits.

The stamp of disapproval came when the American Association of

Museums, which has more than 3,000 institution members, passed

a new set of ethical guidelines the summer after "Sensation"

closed.

Hype vs. reality

Even if the Brooklyn Museum went too far, there was something

off in the media’s revelations of the museum’s funding practices,

writes Andres Szanto, a deputy director of the National Arts

Journalism Program at Columbia University. The press is ill equipped

to handle the juncture of arts and hard news, he writes. The

arts are "feature" section material, more emotional

in response and often less rigorous in its reporting than the

"news" sections, he claims.

For example, writers kept describing Ofili’s painting as "smeared"

with dung, when in fact the dry, lacquered balls of dung were

carefully placed and anything but smeared. A small point perhaps,

but telling in the lack of reporting and the attempt to stir

emotions.

When it came to the largely unknown world of financial relationships

between museums and exhibitions, press reactions went both ways.

Either it was standard practice for a museum to take money from

the owner of an exhibition or it was scandalous. Museum directors

around the country did not help by sending mixed messages, Szanto

writes.

UCLA’s LeRoy Nieman Center for the Study of American Society

bases an interesting essay in the book on UCLA’s survey of 860

visitors to the "Sensation" exhibit.

Forget Chris Ofili, the survey revealed that it was the Chapman

brothers, Jake and Dinos, who most offended museum visitors with

their sexualized metamorphic teenage mannequins.

The disconnect between the reality of viewer response and the

hype shouldn’t surprise – considering that neither the mayor

nor Lehman had seen "Sensation" firsthand before they

made their judgements of it.

"Unsettling Sensation: Arts-Policy

Lessons from the Brooklyn Museum of Art Controversy," edited

by Lawrence Rothfield (Rutgers University Press, $25) can be

ordered at A Novel Idea Book Store [8415 Third Ave. (718) 833-5115]

in Bay Ridge, Community Bookstore [143 Seventh Ave. between Carroll

Street and Garfield Place, (718) 783-3075] in Park Slope and

BookCourt [163 Court St., (718) 875-3677] in Cobble Hill.