Excavating 3.5 million cubic yards of rock

and earth is not an easy feat. Place a city on top of it, add

a population of about 3 million and enclose it with two bodies

of water, and this endeavor suddenly becomes a monumental challenge

for any labor force – especially when the most advanced technology

available at the time is a pick-axe and shovel.

Today, about 4.5 million passengers ride the New York City subway

daily, yet few know how it was constructed or the Herculean efforts

it entailed.

As part of the subway’s centennial, the New York Transit Museum,

in Downtown Brooklyn, has opened a new exhibit dedicated to illustrating

subway construction during the first quarter of the century.

"The City Beneath Us: Building the New York Subway,"

on display through January 2005, is a vivid, visual narrative

of the above- and below-ground obstacles encountered by workers

and engineers during the subway system’s construction.

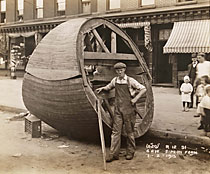

Forty-two photographs, made from vintage prints and film negatives,

tell the workers’ stories and give visitors an idea of what it

might have been like to have lived in the city between 1900 and

1928.

For more than two decades, workers burrowed under the streets,

dissecting the city and peeling away layers of pavement, utility

lines, sewer pipes and telegraph cables to clear the way for

tracks. Their efforts were often mired in dynamite explosions,

cave-ins and collapsing underwater tunnels, taking the lives

of more then 50 workers in the first 25 years and injuring countless

others.

Despite their contributions, the achievements of these nameless

immigrant workers have all but dissolved into memories of a bygone

era. Until now, that is, with the unveiling of "The City

Beneath Us" and the book of the same name written by New

York Transit Museum historians with Vivian Heller.

"We hope [this exhibit] will create a sense of awe and admiration

of the work, labor and human ingenuity involved in the project,"

said Charles Sachs, the Transit Museum’s senior curator. "We

also hope it will reflect the technical and artistic talent of

the photographers who documented the construction."

Due to the scope of the project, public agencies overseeing the

planning, design and construction, such as the Rapid Transit

Commission and the Board of Transportation, meticulously documented

each phase of the project for insurance and legal purposes. Professional

photographers were commissioned to travel underground with workers

and capture scenes before, during and after the construction.

Almost all the photographs remain anonymous, but the cumulative

effect is a collection of visually arresting images – thickets

of utility wires snaking up through an open fissure in the pavement,

workers tangled in webs of underground scaffolding and disastrous

cave-ins capable of swallowing an entire street block.

In selecting images for the show, curators and historians sifted

through more than 150,000 photographs.

"What we found most interesting about the collection is

the variety of photographic processes used," said Sachs.

"Their tools may seem primitive by today’s standards, but

the results are amazing."

At the turn of the century, photographic technology was still

in its infancy. Photographers dragged large-format cameras, lighting

equipment and pushcarts down into the trenches. The caverns had

to be illuminated by arc lights, weighty devices often used for

streetlights or as searchlights on ships, that pre-dated the

invention of Thomas Edison’s tungsten-filament light bulb.

Many of the black-and-white photographs, on display for the first

time, are traditional gelatin-silver prints, which after nearly

a century of lying buried in the archives, have acquired a slight

sepia tint.

Bold blues and whites color a number of the photographs, the

result of an iron-based emulsion process. The combination of

the unique coloring and the artistry of the photography creates

stunning, surreal images out of seemingly banal construction

scenes.

For instance, one photograph, titled "Timbering Inside the

Subway Trench," from the construction of the Fourth Avenue

line in Brooklyn, depicts a man suspended on a limb of scaffolding.

The timber structure extends back in such a way that it appears

to vanish into the infinite like the illusion created when standing

between two mirrors.

Other photographs are more didactic in their content, depicting

various pieces of machinery or specific excavating techniques.

In one photograph, workers hoist a hefty, 20-foot steel ring

into a tunnel opening, a method called "shielding,"

according to engineering historian Joseph Cunningham.

"It works like a gigantic cookie cutter and is used to plow

under the river beds for underwater tunnels," said Cunningham.

The construction teams started on opposite sides of the East

River and met in the middle, joining within an inch. "All

of this was done with mathematics and calculations from surveys,

not computers or lasers," said Cunningham. "It is an

amazing accomplishment."

Still, many of the excavating techniques were not foolproof.

"They were facing a lot of the unknown," said Cunningham,

citing lack of information about structural calculations, material

strengths, geographical strata and safety practices.

"There is a strange mix of materials underneath the city

that people don’t realize are there," he said, such as patches

of quicksand around Union Square and subterranean water under

Canal Street.

A number of the photographs depict cave-ins, sunken trolley cars

and brownstone facades balancing precariously on the edge of

trenches, their only support a slim forest of two-by-four timber

slats. Many of these accidents were the result of the "cut

and cover" method, where workers would dig a section of

the subway trench, relocate the utility wires and cover it with

wooden boards so traffic above could resume. The boards were

often flimsy and a trolley car caught on one loose board could

send the entire makeshift covering into the trench, said Cunningham.

Most workers toiled under these conditions while making less

than $1.50 a day – about $28 today. In the photographs on display,

most of them stare blankly at the camera, peeking above disheveled

bricks and utility lines or from behind bulky machinery.

"They were anonymous when they were doing the work,"

said Roxanne Robertson, a Transit Museum spokeswoman who toured

the exhibit with GO Brooklyn. "But now their faces are immortalized.

They leave a legacy behind them."

"The City Beneath Us: Building

the New York Subway" is on display at the New York Transit

Museum through January. The museum is located at the corner of

Boerum Place and Schermerhorn Street in Downtown Brooklyn. Admission

is $5 for adults, $3 for children and senior citizens. For more

information, visit www.mta.nyc.ny.us/mta/museum/

or call (718) 694-1600.

"The City Beneath Us: Building the New York Subway"

(W.W. Norton & Company, $45) will be available in October

at the museum’s gift shop or online at www.BarnesandNoble.com.