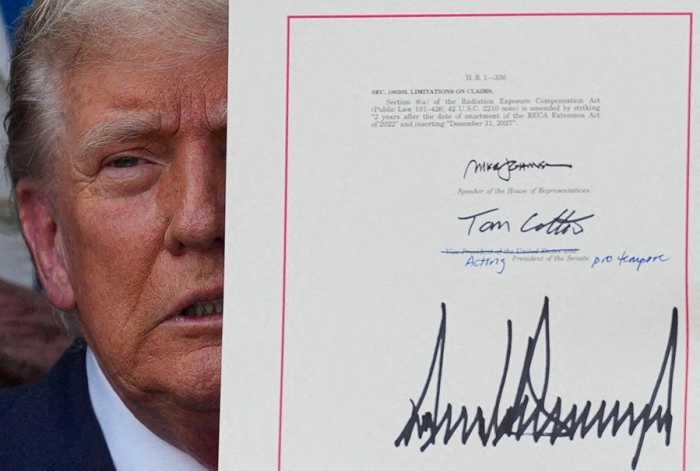

On the 65th anniversary of Medicaid, Brooklyn residents — and many of its hospitals – were bracing for the impact of massive federal health spending cuts included in President Donald Trump’s “Big Beautiful Bill.”

The massive spending bill will likely cost up to 10.9 million Americans their health insurance, according to the Congressional Budget Office, and threatens the futures of hundreds of hospitals — especially safety-net hospitals where many patients rely on Medicaid.

One local safety-net, Wyckoff Heights Medical Center in Bushwick, is trying to prepare itself — and its patients — for an uncertain future.

“We have been there fighting to keep hospitals like Wyckoff open. But now, they will face these new challenges,” said U.S. Rep. Nydia Velázquez, during a July 30 press conference at the hospital. “These cuts will force hospitals like Wyckoff to lay off staff, reduce services, or even shut down entirely. That would leave entire neighborhoods without the care they need.”

About 56% of Wyckoff’s patients are insured by Medicaid, according to a 2022 report. Another 20% rely on Medicare, and 3.5% are uninsured. Since Medicaid doesn’t reimburse hospitals for the full cost of care, facilities like Wyckoff typically have lower revenue and fewer resources.

“In our neighborhoods where poverty rates are higher and many of our neighbors are uninsured or underinsured, Medicaid ensures access to critical services including preventive care, maternity care, mental health and substance care, long term care, emergency services,” said Wyckoff CEO Vail Gache.

About 45% of residents in Velázquez’s district rely on Medicaid, and as many as 2.9 million Brooklyites are enrolled in the program, which provides insurance to low-income Americans and to some people with disabilities.

“Underinsured individuals in underserved communities … face difficult choices,” said Dr. Ralph Ruggiero, chairman of Wyckoff’s OB/GYN department. “They pay for a doctor’s visit, or they spend money on something like food or housing. These are choices we don’t want them to make.”

Locals who lose Medicaid will likely be unable to afford preventive services like regular doctor’s appointments and prescriptions, he said. Without that care, people are more likely to develop serious — and expensive to treat — illnesses and complications from untreated conditions like diabetes, heart disease, and cancer.

Medicaid cuts also reduce the revenue of community health centers and hospitals, he said, forcing them to reduce services or close entirely. Their former patients, left without insurance, would have to seek care elsewhere.

“A surge in uninsured patients may overwhelm hospitals and emergency rooms, so even people with great insurance are going to experience a reducing quality of care,” he said.

Less revenue would likely result in significant layoffs at many safety-net hospitals. Velázquez’s district would likely lose more than 800 hospital jobs, according to an analysis by the Greater New York Hospital Association and the Healthcare Association of New York State, and 1,599 jobs total.

In U.S. Rep. Yvette Clarke’s district, which contains hospitals like SUNY Downstate and Brookdale University Hospital Medical Center, as many as 1,457 hospital workers could lose their jobs, per the same analysis.

Carmen DeLeon, president of DC37 Local 768, said her job as a respiratory therapist would likely be safe for a long time, because she works closely with doctors at the bedside. Staffers who feed and bathe patients, she said, would likely be laid off first.

Hospitals across New York State are already short-staffed, DeLeon said. If the cuts force significant layoffs, patients could be waiting hours to eat or be bathed.

Cuts threaten more than hospital care

Medicaid cuts will leave Brooklynites struggling with much more than hospital bills.

When local Jenn Miles aged out of foster care at age 18, she turned to the Institute for Community Living, an organization that supports adults with mental and behavioral health issues, for support.

“That’s when I found my real home, and the support I needed to heal, grow and start believing in myself,” she said.

When she got pregnant with her son, Miles found a new home with the org’s Emerson Davis Program, which is designed for parents with mental health needs. The program offered resources, parenting classes, and more. Today, Miles lives independently with her son and is training to become a peer counselor.

“I couldn’t have done any of this without Medicaid. Medicaid made it possible for me to have therapy, housing support, medical care and even parenting help,” she said. “If Medicaid gets cut, we won’t just lose services. We could lose our homes, our kids, and our future.”

Teresa Arieta, a parent organizer with El Puente in Williamsburg, said rising rents and food prices are already difficult to manage. Rising healthcare costs will be prohibitive for many.

Arieta was particularly concerned for undocumented and immigrant Brooklynites. In New York, some undocumented immigrants are eligible for Medicaid in emergency situations.

Trump’s Medicaid cuts will exclude some legal residents, like refugees and asylum-seekers, from Medicaid coverage; and will make refugees, asylum-seekers, and people with Temporary Protected Status ineligible for federal assistance under the Affordable Care Act.

“I don’t want to lose my faith. Because it’s hard, the moment that we are living,” Arieta said. “But I know also in the community, they’re aware and alert and coming out to defend what is right. They’re not going to have it. We still have a little power in the streets.”

Maria Pacheco, an immigrant and member of Make the Road New York, had to stop working as a house cleaner when she had a stroke.

She needs physical therapy twice a week and regular therapy to help cope with the anxiety and depression that came with suddenly becoming disabled, she said in Spanish, through an interpreter.

“I went from being an independent person to relying on disability benefits, Medicaid, Medicare, and SNAP just to meet my basic needs and maintain my health,” Pacheco said. “The passage of the reconciliation bill has disproportionately harmful impacts on immigrant New Yorkers like me, and the thought of using these programs is terrifying, as I depend on these programs to survive.”

Robert Comanche, a lifelong Bushwick resident and chair of Community Board 4, said things are “getting harder and harder,” especially for older New Yorkers.

“We’re in 2025 and we’re going backwards,” he said. “We’ve been here all our lives fighting for the same thing we’ve been fighting all our lives, why are we going back?”

As the local population ages and requires more services, he said, those services are disappearing.

But Annette Spellen, who chairs Community Board 4’s civic, public safety and religious committee, said she was grateful to be over 65 and eligible for Medicare — which is not on the chopping block.

I’m fortunate, because I’m retired, I do have medical coverage for the moment, because of my age I have Medicare,” she said. “But what’s going to happen to the younger people? The bottom line is our Congress right now doesn’t seem to care about the lower income people.”

Wyckoff Heights Medical Center is “really the only [hospital] we have,” Spellen said. Days before she headed to the hospital to rally against Medicaid cuts, she had called 911 for a man who was lying in the street on a hot day, speaking incoherently.

Spellen said she was relieved when an ambulance arrived to take him to Wyckoff.

“I thought, they’re going to bring him to the emergency room there and I know they’re going to take care of him,” she said. “Whether he had coverage or not.”

‘We must fight together’

Most of the provisions of the “Big Beautiful Bill” won’t take effect immediately, but Medicaid cuts will begin as soon as January 2026.

Until then, Velázquez urged Bushwick residents to warn their neighbors about the bill and keep up the fight against spending cuts.

“Don’t forget, when Donald Trump was campaigning, he promised the American people that he would not touch Medicaid and Medicare,” she said. “And here we are.”

The congresswoman vowed not to turn her back on “seniors, veterans, and people with disabilities.”

“That is not who were are, and we are here to say that we reject the notion that we are going to turn our backs on vulnerable people in our country for the sake of passing tax cuts for the wealthy and the well-connected,” she said. “This is a fight that we must fight together.”