With personal protective equipment in short supply at the onset of the coronavirus pandemic, Brooklyn creators stepped up to make masks, face shields, and other materials needed to combat the spread of the viral outbreak.

So-called hackerspaces — nonprofit workspaces with shared manufacturing equipment — became hubs for making and distributing the crucial gear, according to one Greenpoint woman who joined in the effort.

“For the first five-six weeks [of the pandemic], every second that I wasn’t working my day job, we were spending every other second making the PPE, working on supply chains, sourcing, design,” said Hannah House, who works out of the Boerum Hill hackerspace NYC Resistor. “We had resources, equipment, and motivated people. So we got together to make PPE.”

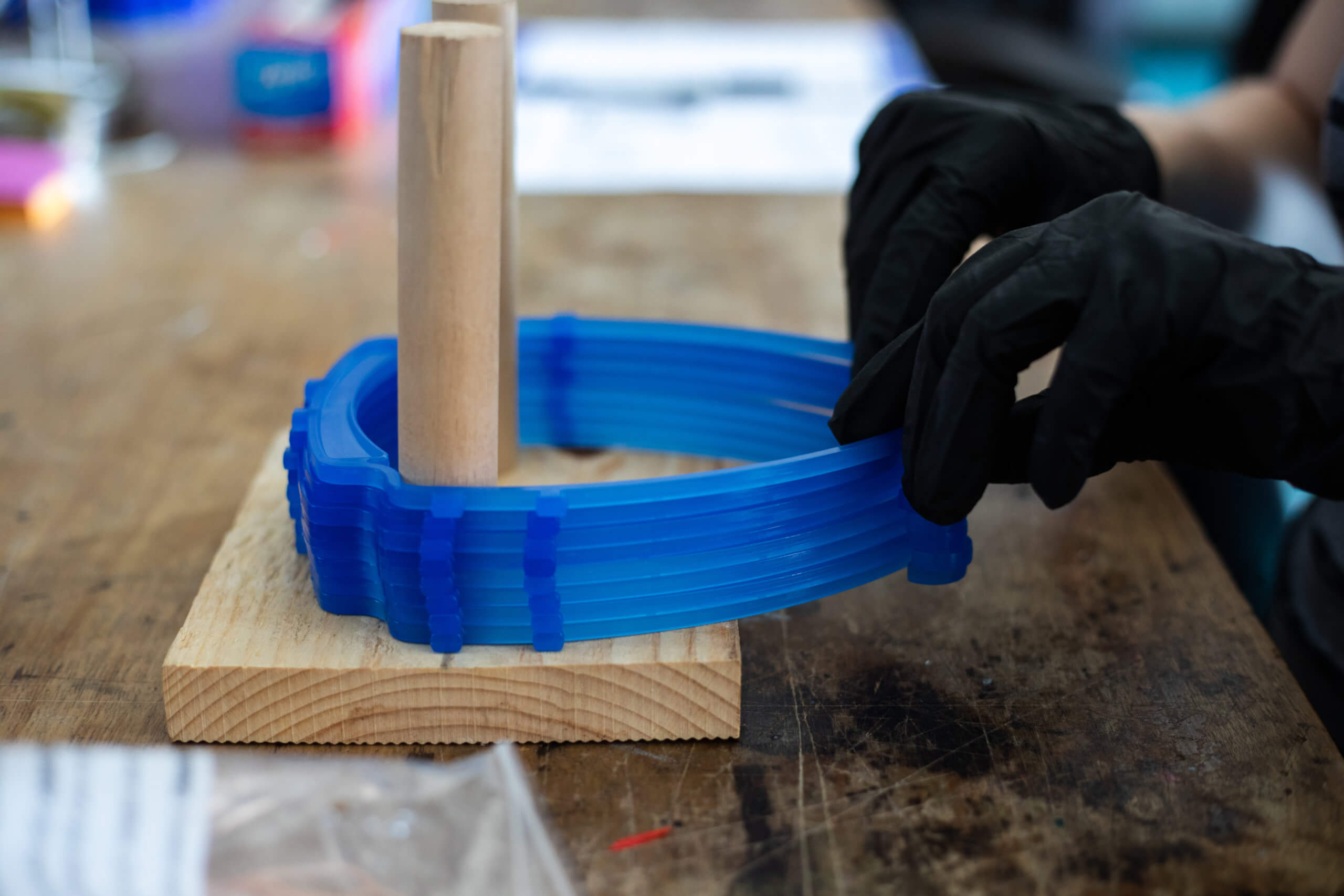

Volunteers of the communal workshop at Third Avenue, between Bergen and Dean streets, used 3-D printers and laser cutters to make face shields, before distributing the goods to places in need via a new citywide network called NYC Makes PPE, which consists of hackerspaces and other organizations like architecture and design firms and universities.

The ingenuity of hackerspaces made them perfect to quickly adapt to the ever-changing realities of COVID-19, said House, who works in branding for her day job and previously used NYC Resistor to make interactive artworks.

“We feel that hackerspaces have a can-do mindset, [often with people that have] an arts or engineering background, and the tools to really rapidly respond,” she said. “We were able to respond more rapidly than the government.”

Requests from health facilities poured in fast, which required a network of organizers to manage distribution of the equipment.

“We were getting hundreds of requests from hospitals, community centers, and everything from nursing homes, you name it, we got requests across the board,” said Jennifer Li, a marketing consultant and board member of NYC Makes PPE.

Once demand for the equipment started to simmer at health facilities, and with the rise of the George Floyd protests in late May, House and other do-gooders shifted to handing out protective equipment at rallies to make sure activists could safely demonstrate without further spreading the bug.

They produced and distributed almost 80,000 pieces of PPE during the past five months, which was demanding but also rewarding, House said.

“It was a lot, hard not to burn out, but also emotionally really healthy to do something to help, especially at the beginning when there were so many massive changes to our life due to the quarantine,” she said.

NYC Makes PPE, which recently filed paperwork to become a tax-exempt nonprofit, has been able to quickly adapt to delivering for populations in need around the nation, such as indigenous communities in the southwestern US, according to Li.

“When we saw a need somewhere else we were able to shift,” she said. “And we’re trying to see where trends are, what are the needs that may come up again.”

Now, the network of creators is preparing for a second wave of the virus, stockpiling resources and providing open source guides online on how to replicate their production and distribution processes.

“We’re sharing knowledge more effectively and learning so that we can help even better next time,” House said. “There are so many people who are willing to help, so how can we structure things so that everybody can get involved and not feel as helpless.”