A nursing home owned by an infamous real estate flipper is being forced to pony up $750,000 in damages to the family of a now-deceased resident — as the facility failed to provide basic health services to her before she died.

A jury at the Kings County Supreme Court found that the Linden Center for Nursing and Rehabilitation in East New York had violated 90-year-old Olive Roberts’s rights and failed to provide proper care that she was entitled to under state public health law, which resulted in her death.

In her final months at the Linden Center, Roberts, who was not mobile on her own, developed a severe pressure wound on her lower back because staff were not shifting her position every few hours, as doctors had ordered.

By the time Roberts’ daughters found out about the wound soon before her death, it was deep, badly infected, and needed intravenous antibiotic treatment. She was transferred first to Kings County Hospital and then to Calvary Hospital, where she passed away in January 2017.

The Linden Center was called Ruby Weston Manor until it was purchased by the Allure Group, by way of shell company Alliance Health Property, LLC, in 2011.

The Allure Group was founded in 2011 by Joel Landau, who, in 2015, paid the city more than $16 million to remove deed restrictions for Rivington House, a nursing home in lower Manhattan, promising to purchase the facility and maintain its function as a nursing home.

In early 2016, with the deed restriction lifted, Landau sold the property to a developer, who planned to turn the lot into luxury condos, for $116 million, walking away with a $72 million profit.

Later that year, CABS Nursing Homes, a nonprofit nursing home chain, filed suit against Landau, seeking to overturn the 2015 sale of CABS Bed-Stuy to the Allure Group after discovering that rather than keeping the nursing home running, as promised during the sale, the Allure Group was shuttering the facility and selling the lot to a developer, who have since announced a 14-story mixed-use building on the site. CABS alleged that Allure had forced residents out of the building with little warning, resulting in more than one premature death.

The Kings County Supreme Court dismissed the charges in 2017.

Six years at the Linden Center

Roberts lived on her own until 2011, when her dementia started to get worse, said her daughter, Deborah Roberts

“She started, like, leaving the house and walking away, just going out,” she said. “I used to go there and stay with her because, at the time, I was a corrections officer.”

Deborah lives in Suffolk County, and when she stayed with Roberts, she would stay the whole week, and bring her kids along with her. She and her sisters had conflicting work schedules, and it wasn’t possible for someone to be at the house at all hours. They decided it had become too dangerous for their mother to stay at home by herself any longer.

“We thought it would be best to put her somewhere that she can get the help that she needs,” Deborah said. “Where somebody could be around her, watching all the time. We don’t want her to do something, she might turn the stove on and forget.”

“That’s the reason why we put her in the nursing home, to get better care, to be around more people her age to talk to, and stuff like that.”

Her sister, Vale, a home care attendant, did most of the footwork of finding a suitable nursing home, Deborah said, and she was happy with the Linden Center.

“She was happy, she used to dance, they would play the music there for them, and she was a dancer, [so] she was very happy,” Deborah said. “That’s why I thought that was the best place for her, when I saw her in that condition. She was happy at the time, when she first got there.”

Vale, who lives in Queens, and their sister, Cheryl, who lives in Brooklyn, could visit regularly, and Roberts’s diabetes and high blood pressure were managed well.

In 2016, her health took a turn, and she became mostly bedridden and nonverbal, and much more reliant on the Linden Center’s staff. To prevent pressure sores, which are common and can be quite serious among older people who spend most of their time sitting or lying down, her doctor prescribed protein supplements and instructed the nursing home to turn Roberts every two hours, to keep her from lying on one spot for too long.

Deborah first became concerned about her mother a few months before she was hospitalized in December, she said, when Roberts developed a sore on her left ankle. It was wrapped in bandages when Deborah arrived, and, she said, when she asked to see it, staff said they didn’t want to unwrap it again, because her sister had recently visited and taken a look at it.

“I didn’t want to cause any problems, so I just let it go,” Deborah said. “I talked to my sisters, they said yes, they did show it to them, and it was beginning to heal a little bit, so they let them not make any fuss about it at the time.”

In December, Vale visited Roberts after work, still wearing her home health attendant uniform, which was the same uniform staff at the Linden Center wore. She went to Roberts’s room and sat her up, Deborah said.

“That’s when somebody, a staff member working there, said, ‘Why do you have Ms. Olive sitting up, she has a stage three bed sore,” she said. “That’s when everything opened up, everything came to the surface. My sister, she said to them, ‘You’re talking about my mother. She has a stage three bed sore, and no one told me anything?’”

Regulations ignored

New York State has strong regulations as part of public health law to guarantee the rights and treatment of nursing home residents, said John Dalli, a longtime elder abuse and nursing home negligence lawyer who represented Davis’ case in court. But they are rarely enforced, and nursing homes don’t usually face penalties for violating them.

“The Department of Health rarely investigates claims of abuse and neglect,” Dalli said. “If it wasn’t for these lawsuits, we wouldn’t be able to hold these nursing homes accountable at all. This is pretty much all we have, and unfortunately, a lot of abuse and neglect goes undocumented, unnoticed, unpunished. Simply because the family or the resident doesn’t know they can ask a lawyer for help.”

Once Vale found out about the bedsore, it was her sister Susan Roberts Bradley, a nurse living in Texas, who demanded the nursing home transfer their mother to the hospital.

“The nursing home didn’t want to send her to the hospital,” Dalli said. “It was apparent to me, and the jury certainly agreed, that they didn’t want her to be sent to the hospital because the nursing home knew if she got sent to an emergency room, the hospital is going to take a picture of this bed sore, and document it as a significant pressure injury.”

By then, the pressure sore was stage 4, the final and most severe classification, and so deep that part of Roberts’s sacral spine was exposed.

Bradley got a private autopsy, a rare request, Dalli said. The coroner’s report said the infected injury had contributed, in part, to Roberts’s death. He filed a lawsuit against the Linden Center seeking damages under public health law.

“The nursing home decided to take the position that they are not responsible,” he said. “That the only reason she developed this pressure injury was because she was old and sick and had comorbidities like diabetes and high blood pressure.”

Records from the Linden Center showed gaps where Roberts was supposed to be receiving wound treatment, her protein supplements, or having her position changed.

“I’m not talking about one or two days where they didn’t document something,” he said. “I’m talking about days and days, literally, where there’s no record of wound treatment being done. I’m talking about an entire month, the entire month of October, there’s absolutely no record of any treatments being done.”

Sitting in the courtroom, Deborah prayed for the strength to get through as she listened to the opposing lawyers talk about her mother, making it sound like Davis was responsible for her own death, she said.

“They treated my mother like she was garbage,” she said. “All we have is just one mother. As a corrections officer, I meet all types of people. I always believe you treat people with respect and kindness, and in return you get the same thing back. But when I see my mother in that condition, I feel like I failed my mother. I should have had more eyes, I should have seen, I should have been there.”

“I just feel like I let my mother down, and I couldn’t do anything because I just didn’t know, I just didn’t know,” she said. “If I had known.”

The settlement and the Allure Group

The jury ordered the Allure Group to pay $750,000 in total — $375,000 for violating Roberts’s rights and $375,000 for her pain and suffering.

The Allure Group’s insurance company, GuideOne, has indicated that they will not pay out, and will likely appeal the decision, Dalli said. GuideOne and the Allure Group declined to comment.

“The Department of Health is not going to say, ‘Oh, a jury found that a resident’s rights were violated, we’re going to go in there and fine the facility for that,” Dalli said. “In fact, the nursing home themselves isn’t really directly affected by this verdict, because they have insurance that covers these instances.”

Deborah said the verdict was comforting, but a little hollow.

“I think that in this country, nursing homes should be held more accountable for their actions, they should be put out of business for the way my mother was treated,” she said. “You cannot treat a human being like that and get away with it.”

New regulations enforcing adequate staffing and increased budget restrictions at nursing homes came into effect in New York State on January 1. The budget restrictions mandate that at least 70 percent of revenue is spent on resident care, with a portion of that spent on “resident-facing” staff, who provide care. The law also caps the revenue a nursing home can make at 5 percent of their non-operating expenses.

“All it does is it puts a number on what can be shown on the books as a profit,” Dalli said. “However, the way these nursing homes make money is not in operating the nursing home.”

Some operators also own or have stake in construction companies that contract with the nursing homes, he said, and they make money there.

“Most importantly, where they really make their money, is they create these consulting companies, or these managing companies, that they pay a monthly fee to, that are frequently owned by relatives of the operators, if not the operators themselves.”

So that monthly fee, which can be tens of thousands of dollars per month, is siphoned out of the nursing home’s budget and into the owner’s pockets, Dalli said.

Ruby Weston, who owned the Linden Center and Marcus Garvey Residential Rehabilitation Pavilion before they were sold to Allure, paid nearly $87,000 in a 2016 settlement after a lawsuit filed by the Attorney General found she had been paying herself a $500,000 salary and had paid her son more than $1 million. Both facilities were purchased by Allure in 2011.

Landau, the chair of the Linden Center and co-founder of the Allure Group, is also the co-founder of two private healthcare investment and acquisition companies, Aurora Health Network and Pinta Capital Partners.

Last month, more than 100 nursing home operators filed a lawsuit against health department commissioner Mary Bassett in an attempt to block the law.

Among the plaintiffs are Alliance Health Operations, LLC, the Linden Center’s operating company, which was part of the Davis lawsuit, and Williamsburg Services, LLC, which is associated with the Bedford Center for Nursing and Rehabilitation, another Allure facility.

In 2016, then-Attorney General Eric Schneiderman blocked the sale of two nursing homes to Allure, but reached a settlement with the company and allowed the sales to go forward two years later.

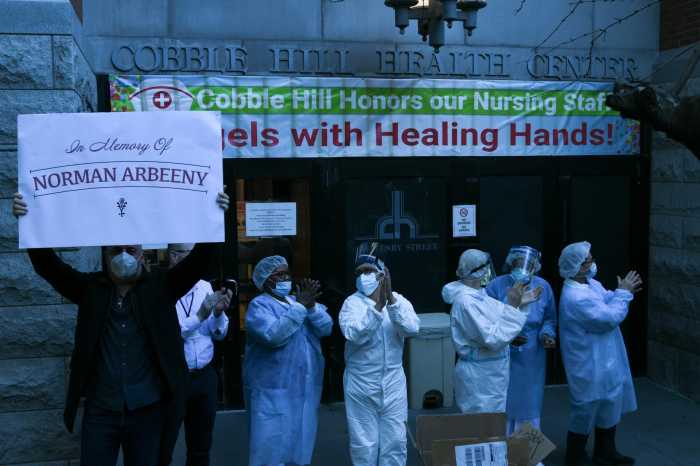

This year’s settlement isn’t the only trouble the Linden Center has been in. Early in the pandemic, employees reported that bodies of residents who had died from COVID-19 were left in the same room with living patients, and that staff did not have adequate PPE. Last fall, employees rallied outside the Center, calling for pay raises and bonuses as part of contract negotiations with their union.

While no health or infection control violations were noted in recent inspections, according to Medicare.gov, the facility was significantly understaffed.

The family matriarch

After her mother’s death, Deborah warned her friends from placing their parents in nursing homes.

“I talked to my son, I said, please don’t put me in a nursing home, please keep me home until my time comes,” she said.

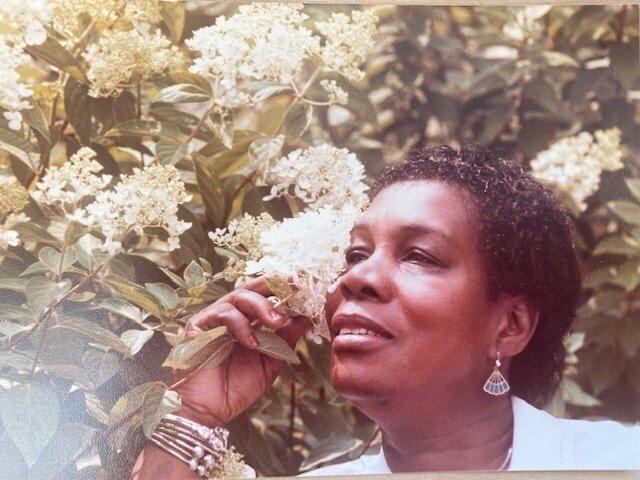

Roberts and her four daughters immigrated to the U.S. from Trinidad and Tobago — Davis first, in the 60s, she said, with her daughters following in the 70s and 80s. Roberts was the matriarch, the head and glue of the family, Deborah said.

“My mom was a peaceful, loving, religious person, a sweetheart,” she said. “Everybody loved her, respected her in the neighborhood she lived in. She always gave the younger generation advice, we called her the mother of everybody, because she thinks she’s everybody’s mom.”

She loved window shopping and dancing and the annual parades on Eastern Parkway, she said.

“We loved her so much, too much,” Deborah said. “She used to have us laughing all the time. No matter what problems you’ve got, you just talk to her, she’ll have you going.”

She and her sisters talk about their mother all the time, she said, remembering the good times they had with her to ease the pain of her loss.

“We miss her very, very much,” she said. “She was the head of the family. Many days I just talk — I look at her photo, I just talk, I say ‘Mom, I miss you so much.’”

Correction 2/1/22: This story previously referred to Olive Roberts as Olive Davis. We regret the error.