A row of four 19th-century landmarked houses on Downtown Brooklyn’s Duffield Street will remain intact for now after the city’s Landmarks Preservation Commission rejected plans to gut their interiors and alter their facades to accommodate a 33-story residential tower. The LPC directed the design team back to the drawing board.

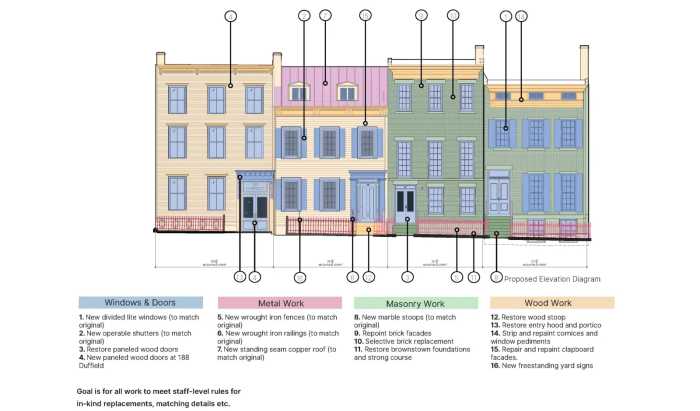

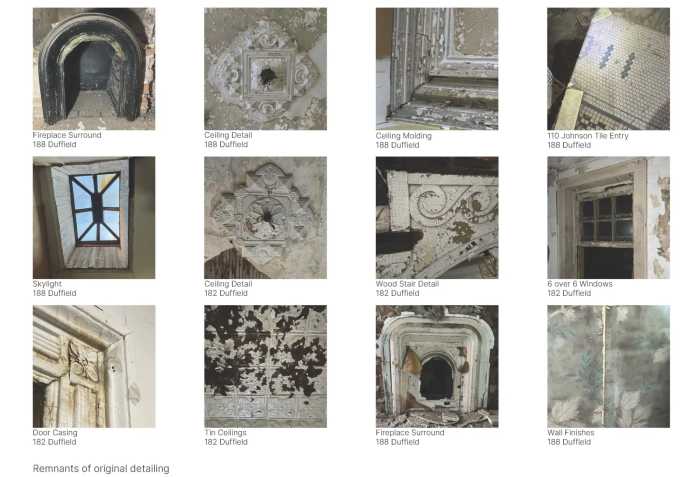

Developer Watermark Capital had proposed combining the interiors of the historic homes, modifying an entrance, and partially reconstructing the roofs, interior walls, floors, and rear facades, while erecting the tower behind them. Architects Drew Hartley of Acheson Doyle Partners Architects and David West of Hill West told the commissioners the plan would preserve the houses’ character and offer adaptive reuse after years of vacancy and deterioration.

But at Tuesday’s hearing, commissioners and members of the public unanimously disagreed. While some commissioners supported the idea of a tower on the site, all objected to how it integrated with the landmarked houses and to the scale of alteration required.

“I do think as an existing property that has had the historic houses specifically protected and moved here to be saved, any solution here needs to celebrate those houses and work with them in the way that makes the proposal and the existing fabric a win-win. Unfortunately, that’s not what I’m seeing in this proposal,” Commissioner Stephen Chu said.

“The houses are diminished severely in scale with the proximity of the tall tower, there’s so much demolition, it’s hard to tell what is left of the fabric of those houses. The rear is being removed. The roof is being rebuilt to be fireproof. Many of the floors are being taken out…party walls are being affected…there’s just too much and at the end, too little left of what was to be protected on the site.”

The four houses, 182 through 188 Duffield Street, are rare survivors of a once-vibrant downtown residential community. Built between the 1830s and 1847, they were home to lawyers, teachers, builders, and merchants. Redevelopment beginning in the 1970s with Fulton Mall and continuing with MetroTech in the 1980s erased most low-rise homes in the area.

Moved from Johnson Street in the 1990s and designated landmarks in 2001, the houses were owned by Forest City Ratner, which pledged to maintain them as part of its MetroTech development deal. In 2022, Watermark bought the site through an LLC for $10 million. The broker said the buyer planned to preserve the houses and give them “functional utility.” Though once slated for offices and nonprofits, they have sat empty for decades.

Hartley said the new residential building would rise directly behind the townhouses, which would be incorporated into the project. The entry would run through 188 Duffield St. into a triple-height lobby using the houses’ rear facades as an interior wall. The ground floor of 188 would contain a cafe or small retail space, with an amenity area for residents above. The other three houses would form community and amenity spaces.

“So we are restoring the facades and having this adaptive reuse to these buildings that really have been underused, and we’re giving them life and giving them a use,” he said.

However, the plan also calls for removing the porch at 188 Duffield for ADA compliance, replacing roofs and framing with noncombustible materials, removing party walls and parts of rear facades, and other major changes.

“These townhouses were relocated here with the intent of being reused, either as houses or for other purposes,” West told the commission. “However, they’ve remained virtually unused for over 30 years, their condition has deteriorated, and their original use of single family homes is no longer realistic in this dense, commercial residential neighborhood.

He said the site was ideal for high-density housing, calling the proposal “a balanced approach that achieves appropriate scale and density while preserving the essential character of the historic townhouses at street level. As with any project, there are trade-offs.”

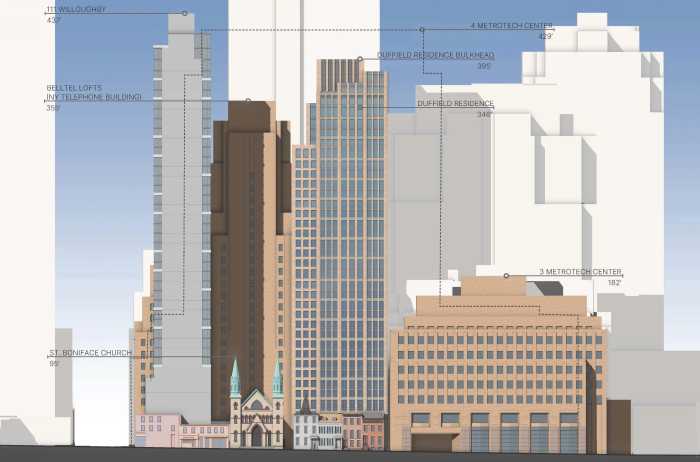

West said the tower would rise 33-stories and 395 feet, set back 35 feet (encroaching over the landmarked roofs), with 99 apartments including 20 affordable units. The facade would feature warm buff brick, metal spandrels, and gray window slab covers.“The main front facade uses a two-story grid inspired by the verticality of the townhouse windows,” he said, while “the setback portion features a flat hall with punched windows, referencing both the townhouses and the Ralph Walker building behind the site.”

As part of the pitch, the design team used four projects as precedents: the Robert and Anne Dickey House at 67 Greenwich St. in the Financial District, 315-317 Broadway in Tribeca, 44-54 9th Ave. n the Gansevoort Market Historic District, and 251-253 Fifth Ave. in NoMad. Both members of the public and commissioners took issue with the selection.

Commissioner Michael Goldblum said none of the projects were relevant to the Duffield Street houses, adding “there’s no question that the frontal reading of this proposed volume would completely overwhelm the historic buildings. I just don’t see a way around it.”

When Goldblum asked why it was economically impractical to restore the houses for residential use, West replied, “If it worked, it would have been done.” Goldblum called that answer “completely unsatisfying.”

Other commissioners said the landmarked houses should drive the design process and warned the tower would eat the rowhouses, stripping them of the qualities for which they were protected.

Sixteen members of the public spoke on the proposal, all in opposition, including representatives from community and preservation groups. Peter Bray, co-chair of the Downtown Brooklyn Landmarks Coalition, said the plan belonged in Las Vegas, “where everything is just a replica of history and there’s nothing real or authentic to it.”

“How, in good conscience, can the LPC consider a project that would fundamentally alter the integrity of these buildings, making them a mere appendage of a 33-story tower, and robbing them completely of their original character and historical significance, they would just be a lobby to the building,” Bray said.

Chris Young of the Downtown Brooklyn Community Association said a petition opposing the proposal had gathered more than 550 signatures.

“The current plan does not honor the history of these homes, nor the reason for which they were saved in the first place, to commemorate the vibrant, middle class neighborhood of Downtown Brooklyn and its rich historical importance of the development of 19th century Brooklyn,” Young said. “There are more appropriate ways to restore and bring these houses, these historic landmarks, back to life. It needs a little more imagination than what we’re seeing here.”

Other speakers emphasized that the houses represented not just architecture but the lives of working Brooklynites.

“They’re not just unused shells,” Erin Hayes said. “They should be brought back to life again. To erase that history now by building this building would be an affront to the reason the buildings were saved in the first place and the history of these homes.”

William Vinicombe, former chair of CB2, recalled seeing the houses moved in the 1990s.

“These houses are directly tied to the story of Downtown Brooklyn, its working class roots, its historic connection to the important role of the abolitionist movement, and its close proximity to the AME churches, the Duffield Street houses also reflect the lives of immigrants and working people who helped build New York City a living record of our city’s social and economic evolution.”

Alina Gonzalez, who lives with her family in the BellTel Lofts, called the proposal “an act of erasure.” “Allowing this project to move forward tells the community and the world that profit matters more than people, that height matters more than history, and that our cultural memory is expendable,” she said.

Jeremy Woodoff, who worked for LPC during MetroTech’s review, said the plan amounted to the demolition the houses had been protected from, “with no more than the false front of a Hollywood movie set remaining.”

“The proposal before you today is an audacious attack on preservation and environmental law, gutting the historic interiors, eliminating floors entirely, replacing the buildings behind their front facades, removing the stoop of 188, cantilevering over them, and altering the front and rear settings. None of this follows the Secretary of the Interior’s Standards or good preservation practice,” he said.

Sherida Paulsen, who was LPC chair when the houses were designated, said the houses were intended to be restored and retained in full.

“The project that they should be looking at as precedent is none of the ones that they referred to, but is the Harrison Street houses on the Lower West Side near the World Trade Center,” she said. “I think the commission should direct this applicant to rethink this entire proposal with the basis being to preserve the houses as originally intended, as the city, state and federal government intended.”

Representatives from the New York Landmarks Conservancy, Historic Districts Council, and Victorian Society also opposed the plan. HDC called it “inappropriate in the extreme,” and John Graham of the Victorian Society said it was “an appalling example of facadism work, which will reduce these four historic buildings to a decorative skin residents walk through on route to their elevators.”

“We do not believe that it’s possible to build foundations for a 437 foot tower right next to buildings which are over 150 years old without damaging the landmarks. Nor do we believe it is good preservation practice to approve work which can endanger individual landmarks with the statement that they will be monitored by DOB,” he said.

Several speakers also questioned why the developer had been allowed to let the houses fall into disrepair and challenged claims that restoring them as residences was unfeasible. LPC received 23 letters opposing the plan, and both Community Board 2 and the Brooklyn Heights Association called for its rejection.

Closing the hearing, LPC Chair Angie Master said most commissioners were concerned with the level of historic fabric being removed, adding, “I think we may have to go back and rethink this proposal.”

This story first appeared on Brooklyn Paper’s sister site Brownstoner.