Mayor Bloomberg’s proposal to charge drivers $8 to enter Downtown Manhattan is an unfair burden on Brooklyn motorists, pols said this week, even as traffic experts said it could ease gridlock throughout the borough.

The so-called “congestion pricing” scheme would require most motorists who drive below 86th Street in Manhattan to pay the fee between 6 am and 6 pm. The mayor says his goal is to reduce traffic and pollution while generating revenue for mass transit.

But Brooklyn electeds weren’t buying it.

“It’s a regressive tax on working middle-class families and small-business owners,” said Rep. Anthony Weiner (D–Sheepshead Bay).

Councilman Vincent Gentile, a Bay Ridge Democrat, chided the mayor for “punishing Brooklynites who are forced to drive due to a lack of an adequate public transportation.”

Bloomberg insisted that the “punishment” to city residents would be nominal because most people who drive into Downtown Manhattan aren’t from the five boroughs. Half of the money raised through “congestion pricing” — roughly $380 million in the first year, Bloomberg said — would be paid by out-of-towners.

And anything that gets those people off Brooklyn streets is a good thing, said Sam Schwartz, a traffic consultant.

“[Brooklyn] suffers from a huge number of vehicles that have neither origin nor destination in the borough, but instead are avoiding the Brooklyn–Battery Tunnel and Queens–Midtown Tunnel and going to the free bridges,” said Schwartz. “They’ll hop off the Gowanus and meander the streets of Downtown Brooklyn. They’ll get off the BQE and ride the local streets.”

Schwartz reckoned congestion pricing would help in two ways.

“It will straighten out people’s trips — they’ll no longer go out of their way to avoid tolls,” said Schwartz. “And congestion pricing has been shown to have a 15-percent reduction in traffic overall, which translates into fewer cars on city streets.”

Details haven’t been fully fleshed out, but regular motorists would pay the $8 fee, while truck drivers would pay $21. Drivers moving within the zone would pay $4. The fee would not apply to drivers who use the Brooklyn Bridge to connect directly to the FDR Drive, but it is unclear how congestion pricing would affect Manhattan Bridge drivers, who do not have a direct connection to the highway and enter Manhattan on Canal Street, which is within the $8 zone.

Instead of tollbooths, there would be a network of cameras enforcing compliance.

The mayor also stressed that roads — and subway, rail and bus lines — would be improved before the congestion-pricing scheme is enacted.

Unveiling the proposal on Sunday, Bloomberg laid out a doomsday scenario if congestion pricing, plus dozens of other initiatives, were not instituted.

“By 2030, rush-hour conditions could extend to 12 hours every day,” the mayor said. At the present, the four counties with the longest commute times in the nation are, in order, Queens, Staten Island, the Bronx, and Brooklyn.

The Mayor’s plan is modeled on a similar program implemented in London in 2003, which has received mostly rave reviews, though on Feb. 24, the Economist reported that, “London’s lessons are a mixed bag.”

While congestion initially fell up to 30 percent, “roads are now only 8 percent less clogged than before 2003,” according to the magazine.

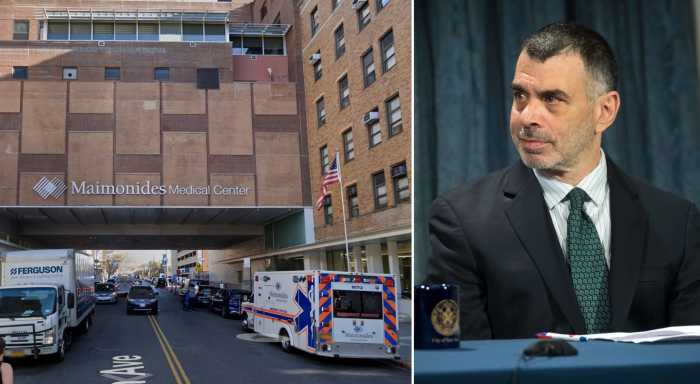

Despite the criticism, London’s experiment helped sway Bloomberg to consider congestion pricing, and looks to be swaying Borough President Markowitz, too.

The Brooklyn Beep, once a fierce opponent of anything that smacked of a toll on East River bridge crossings, visited London in November. Upon his return, he told The Brooklyn Paper that he was fascinated by the policy.

“I’m intrigued because when I was in London, there was a reduction of traffic in the center of the city, thereby encouraging more people to walk,” said Markowitz.

“I don’t know if what is being done in London could be transferred here to New York City. However … it is certainly worthy of looking into.”

This week, he told The Paper that he continues to “have many concerns [about congestion pricing]. However, it is worthy of full review. … I haven’t come out against it, nor have I come out in support of it.”

Markowitz’s ambivalence is shared by Carolyn Konheim, a Brooklyn-based traffic expert.

“Brooklyn and Queens residents would benefit very greatly by getting rid of the congestion that fans out from the bridges and that is messing up the quality of life,” said Konheim.

But she cautioned that “the devil is in the details,” and that the program may prove so cumbersome to enforce that it ends up depleting the public coffers, rather than filling them.

The congestion-pricing proposal was the most controversial of 127 initiatives put forth by the Bloomberg Administration on Earth Day, April 22, in an effort to meet the colliding challenges of over-development, global warming, and a city population that is expected to grow by one million by 2030.

“As the city continues to grow, the costs of congestion — to our health, to our environment, and to our economy — are only going to get worse,” he said. “The question is not whether we want to pay, but how do we want to pay. With an increased asthma rate? With more greenhouse gases? Wasted time? Lost business? And higher prices? Or, do we charge a modest fee to encourage more people to take mass transit?”

Opposition from Brooklynites and other “outer” borough politicians isn’t the only obstacle Bloomberg’s plan faces.

The proposal would have to win state approval, and is sure to encounter opposition among commuters from outside the city, not to mention trucking interests and some businesses.