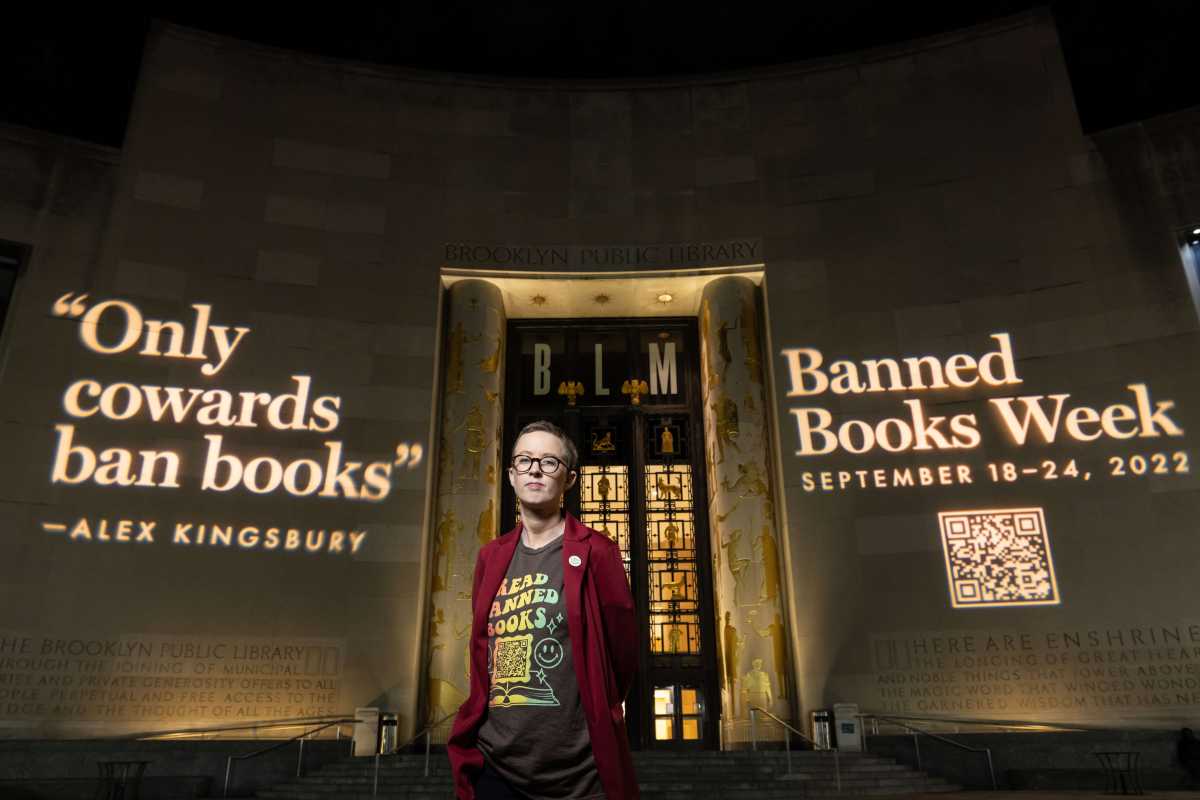

As the unprecedented effort to ban books in classrooms and libraries continues to gain traction throughout the nation, Brooklyn Public Library is fighting back — and not just in New York City. Hoping to address and educate the community about the dangers of censorship, BPL last week held “Banned Books Week.”

“This year, there have been more [book bans] than ever before, for as long as [the American Library Association] has been keeping track,” said Fritzi Bodenheimer, a BPL spokesperson. “The new bans are not only more numerous, but they’re more organized and political in nature. Sadly, they’re more effective as well.”

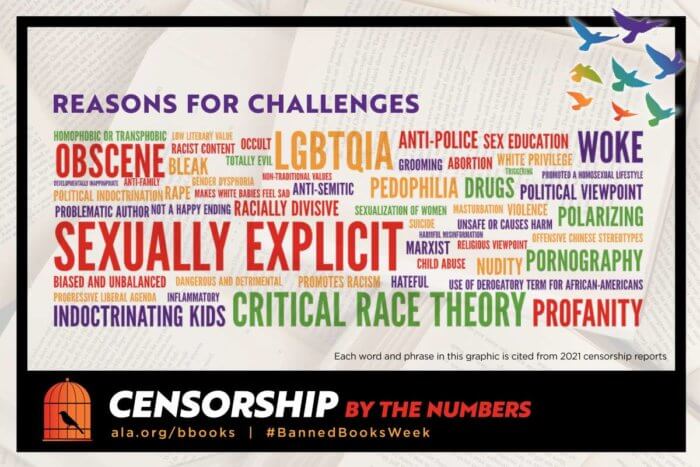

From March 2021 to July 2022, 86 school districts in 26 states have banned more than 1,400 books in total, according to PEN America. The bans affect nearly 3,000 schools and over 2 million students, and a number of book bans were carried out at the directive of local elected officials.

Banned Books Week consisted of three events, all featuring speakers who are on the front lines of the fight against book bans.

“Banned Camp”, a virtual event that took place Tuesday, featured a discussion from teens a part of Austin Public Library’s Banned Camp initiative. On Wednesday, “Open Eyes: Banned Books, Kids, and the War on Reading”, a discussion featuring Washington Post Reporter Hannah Natanson, took place virtually. The week closed with “The Battle for the Right to Read What You Want”, a discussion featuring Summer Boismier, a teacher from Norman, Oklahoma who was suspended after sharing BPL’s “Books Unbanned” program with her students.

“Books Unbanned“ is a new online resource founded by the Brooklyn Public Library that gives all 13-21 year olds, even those who live outside of New York City, access to a collection of hundreds of thousands digital books and learning databases.

“Six months ago, we started our Books Unbanned program,” Bodenheimer said. “We opened up our digital collection of about a half million items to all young people, ages 13 to 21, regardless of where they lived so that anyone would have access not only to banned books but to our entire collection. We’ve had over 5,000 inquiries from teens all across the country in all 50 states and the District of Columbia.”

PEN America found that the vast majority of book bans did not follow best-practice guidelines set by the National Coalition Against Censorship and the American Library Association, which typically involves filing formal complaints and a subsequent investigation into the book’s content.

According to the New York Times, those in favor of the book bans argue that parents should be the ones controlling what kids are allowed to read, not schools. Furthermore, parents in favor of book bans argue that they should be the ones introducing their children to certain topics like the LBGTQ+ community or race. A number of the books banned in schools and libraries last year dealt with racism or featured main characters of color, according to PEN America, and 33% of books banned featured LGBTQ+ characters or themes.

In addition to Books Unbanned, BPL launched their “Intellectual Teen Freedom Council,” where local teens can discuss the project, their favorite banned books, and how they can help young readers across the country who are dealing with book bans.

“It’s about the books on the shelves, but it’s also about something bigger,” said Bodenheimer. “In our country, we have freedom of press, freedom of speech and freedom of religion, because of democracy. We think of reading as an extension of that. That is the promise of both a public library and of democracy, that you can read what you want, without judgment. That’s important whether you love to read or not. These are the principles of democracy.”