Talk about government waste!

City officials want to spend unnecessary cash to make a water-filtration facility required for the cleanup of the toxic Gowanus Canal bigger than it needs to be, according to the Feds overseeing the cleanse.

“Why build bigger and more expensive if you don’t have to?” said Environmental Protection Agency project manager Christos Tsiamis.

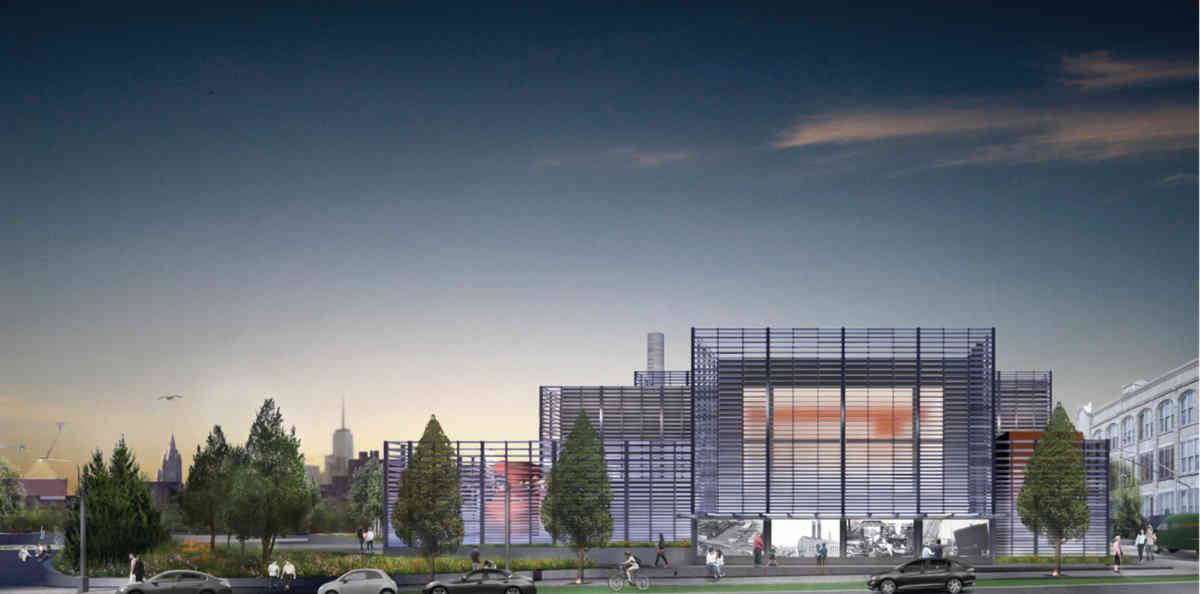

In May, leaders of the city’s Department of Envrionmental Protection presented draft plans for the so-called headhouse they want to build on the Butler Street lot currently occupied by the ancient Gowanus Station building, following Council’s approval for the agency to use eminent domain to seize that canal-adjacent property and a neighboring Nevins Street parcel so one of two massive sewage-storage tanks also required for the canal cleanup can be buried beneath the land.

The plans, which also call for creating an open-air public space next to the headhouse, could come with a price tag as high as $1.2 billion once final costs for construction, land acquisition, and the tanks’ installation are tallied, city officials said at the time.

The agency employees claimed the headhouse, which will filter poo and other waste from canal water destined for the cistern underneath it, would stand no more than seven-stories tall, and incorporate elements salvaged from the Gowanus Station they intend to demolish — even though many locals argued the two properties boast enough area between them to build the new structure without destroying the old.

And now Tsiamis and his colleagues are doubling down on the locals’ arguments, agreeing that it’s possible to create a smaller filtration facility without compromising its function.

“What we have been trying to do is produce a design for the headhouse in a manner that carries out the engineer functions, and has the least visual impact on the community,” said the federal agency’s attorney, Brian Carr.

Tsiamis sent the city a letter last month suggesting cost-saving ways to shrink the building so it better blends in with neighbors, and asked officials to respond by June 18, but the deadline came and went with no feedback, he said.

And the city’s silence showed a blatant disregard to Tsiamis and his agency’s authority over the scrub, a chain of command that was established back in 2010 when federal officials designated the Gowanus Canal a Superfund site.

“What we have is a non-cooperating party,” he said. “New York City is laughing right now at this, but we have a legal document, and if you don’t follow this directive, you’re forced to remedy, or pay penalties.”

But reps for the city’s Environmental Protection Department denied Tsiamis’s accusation that the agency ignored his missive, claiming its leaders responded suggesting a meeting be set up about the letter, and argued it hasn’t done anything wrong because designs for the headhouse are only preliminary, and hinge on an in-the-works agreement the Feds are drafting with the state’s Historic Preservation Office that would require preserving two facades of the 1913 Gowanus Station exactly where they stand.

“It’s really in flux right now,” said Alicia West, who conducts community outreach for the city environmental agency.

Plans for the headhouse, however, will need to go back to the drawing board entirely if the city does not seize the Nevins and Butler Street properties or work out a private deal to buy them by 2020, at which point the Feds will proceed with their original plan to stick the sewage-storage tank in the grave of Gowanus’s beloved Double-D pool, which must be removed and replaced as part of the cleanup of the canal.