Broadway Junction, one of Brooklyn’s busiest subway stations and most crucial transfer points, is finally set to become accessible for people with disabilities with the construction of seven new elevators, Senator Chuck Schumer announced Monday.

The feds have allocated $15 million to construct the elevators, as well as ramps, platform modifications, and signage compliant with the Americans with Disabilities Act. The labyrinthine Brownsville train complex is a meeting point for the A, C, L, J, and Z trains, and is also a few blocks from a Long Island Rail Road stop.

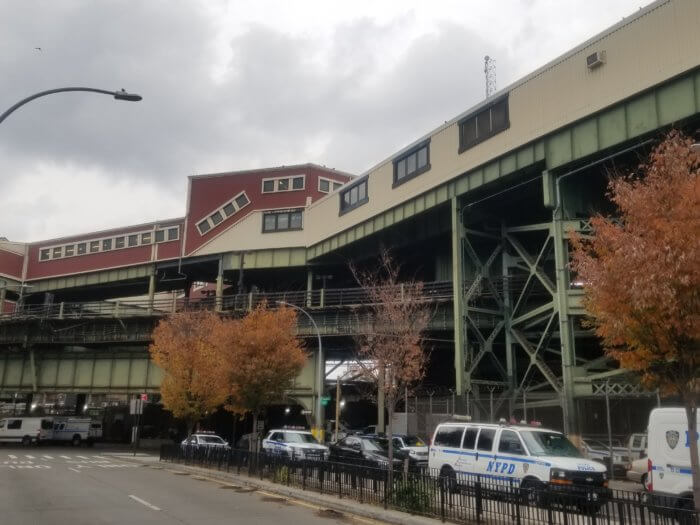

The station features platforms both high in the sky and well below the surface, connected by a maze of corridors and stairways for the thousands of straphangers filing through to transfer lines each day. But 31 years after the ADA’s passage, it is still inaccessible to people with disabilities.

“This station is getting the attention it needs and deserves,” Schumer said at a Nov. 22 press conference at the station. “Equity, fairness, that is very, very important.”

“It’s gonna make it more connected, it’s gonna allow all New Yorkers to use it,” the Senate Majority Leader added. “And it’s gonna be an even more important hub than it has been before.”

The $15 million is coming from the Department of Transportation’s RAISE grants, which stands for Rebuilding American Infrastructure with Sustainability and Equity. The RAISE money is not coming from the recently-passed Bipartisan Infrastructure Framework but from money DOT already had; Schumer said he heard last week from Secretary Pete Buttigieg that the city would get a RAISE grant for Broadway Junction, as well as $2 million to “reimagine” the Cross Bronx Expressway.

Schumer noted, however, that the infrastructure bill secures $7.5 billion for similar projects in New York.

DOT estimates the full project cost at nearly $213 million. Broadway Junction was one of 66 stations the MTA included in its $51 billion 2020-24 capital plan as a stop that would get elevators to become ADA-accessible. MTA spokesperson Eugene Resnick said that the elevators are funded in the capital plan (with the federal grant as additional support), and that the project is currently in the design phase with a construction contract expected to be awarded in 2023.

Despite its status as an important transfer hub for Brooklyn and Queens commuters, the station cannot currently be navigated by wheelchair users, and can only be navigated with great difficulty for those who can walk but have limited mobility.

At present, area commuters with disabilities are out of luck: on the A/C, the nearest fully-accessible stop three stops away is Utica Ave, while on the J/Z, it’s six stops away at Flushing Avenue. On the L, the nearby Wilson Avenue stop is accessible only on the Manhattan-bound side and the nearest fully accessible stop is Myrtle-Wyckoff Avenues, four stops from Broadway Junction.

The inaccessibility means that those commuters with disabilities cannot use the station as a transfer point on equal grounds as their able-bodied brethren. Speakers at the press conference noted that the station’s inaccessibility is a particularly stark reminder that for decades, governments have failed to invest equitably in infrastructure, and disabled riders of color have borne some of the worst brunt of the MTA’s failure to make the system fully accessible.

“We want elevators for everybody,” said US Rep. Hakeem Jeffries, who represents Brooklyn in Congress and is one of the most powerful Democrats in Washington. “Broadway Junction here, of course, is one of the most important transportation arteries in the City of New York, and it serves working-class people. And we’re gonna give working-class people and those with physical challenges a state-of-the-art station.”

Despite being three decades out from the ADA’s passage, only 131 of the subway’s 472 stops are accessible, a paltry 28 percent. In Brooklyn, 36 out of 170 stations are accessible, about 21 percent.

The system’s lack of accessibility has long frustrated disabled riders, some of whom have taken to the courts. One lawsuit, De La Rosa v. MTA (formerly Forsee v. MTA), filed in 2019 by a coalition of disabled riders and advocates, contends that the MTA has frequently skirted the ADA when doing renovations by failing to install an elevator as part of them. One such renovation deemed discriminatory by the plaintiffs was at Broadway Junction, where the MTA constructed new staircases without installing elevators.

“The MTA has spent millions of dollars without doing the accessibility work,” said Joe Rappaport, executive director of the Brooklyn Center for the Independence of the Disabled, a plaintiff in the case, in an interview with Brooklyn Paper. “They didn’t think they had to. What they said in response to our lawsuits is, we disagree. But the ADA is pretty clear about this.”

Asked whether he is confident the elevators will be installed in a timely and efficient manner, Rappaport was cautiously optimistic.

“I think if they get the money, and the senator has designated it for this project, it will get done,” he said. “I wouldn’t suggest the MTA doesn’t waste money, however.”