Dozens of anti-gun violence advocates gathered for a demonstration in Bedford-Stuyvesant on July 16 following a recent uptick in shootings across Brooklyn, including the tragic shooting death of a one-year-old boy last week.

Anti-violence groups began their evening procession outside the Gates Avenue office of the community organization Save Our Streets Bed-Stuy (S.O.S.), where advocate Shadoe Tarver kicked off the march — but not before sharing some harrowing news.

“I apologize for starting five minutes late, but that’s because we literally just heard that there was another shooting,” Tarver said. “I’m upset y’all and I’m hurt … that’s why we’re here today, because we have to show everybody that we’re not accepting this, that we’re not cool with this, that this is not business as usual.”

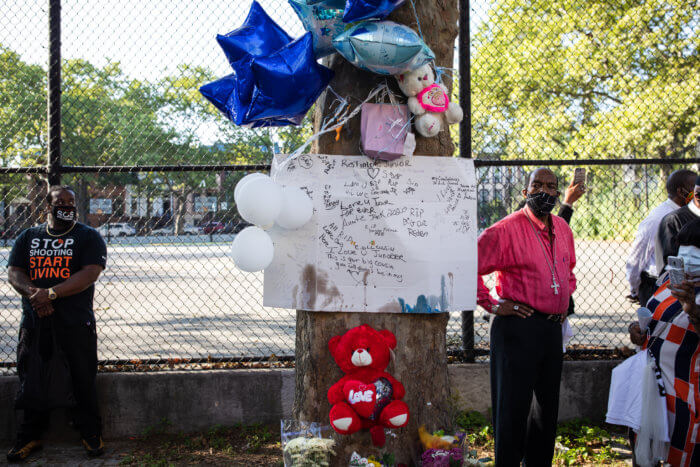

One-year-old Davell Gardner was shot and killed while sitting in his stroller at a cookout near Raymond Bush Playground on July 12 — shaking an already distraught city reeling from the spike in violent crime.

The Bedford-Stuyvesant march kicked off a weekend of outreach in the neighborhood to continue the long-term healing of violence in the city.

“We look at violence, especially gun violence, as a public health issue and not a criminal issue,” said Tarver, S.O.S.’s associate director of community safety. “We believe that we can stop the spread of violence just like you can stop the spread of a disease, which means vaccinating or taking away the risk factors by changing behaviors and giving people resources.”

S.O.S. Brooklyn, a project of the Center for Court Innovation, is New York’s first and longest-standing cure violence collective, that operates in Bedford-Stuyvesant and Crown Heights.

As the more than 100 local demonstrators marched through the neighborhood where Gardner was killed, neighbors came out to their porches, some tearing up and raising fists in solidarity.

“I was born and raised in this neighborhood and to see the destruction and the ignorance that’s happening, it touches,” said Chris, a 48-year-old resident of Madison Street, who did not want to disclose his last name. “It’s time to come together. That’s power walking down the block.”

When the march arrived at a memorial for Gardner outside Raymond Bush Playground, participants mourned as a community and shared grievances with the current spate of violence.

Nyrearra Mclain, 19, an outreach worker with S.O.S. and the mother of a one-year-old girl, took the microphone.

“I can only imagine how this mother is feeling,” she said. “The thought of not holding her child anymore, not getting to see him take his first steps. I hope and I pray that she finds justice, peace and healing through this process.”

An outreach worker with cure violence group Man Up! reminded the community of shooting responses that the groups had organized in past years around Bedford-Stuyvesant. These organizations typically respond to shootings within 72 hours to send a message that the community doesn’t tolerate violence.

“I’m tired of doing shooting responses … we’re losing generations,” said 24-year-old Shayquan Moody. “This is our community, we gotta take back our community.”

After the rally, the anti-violence groups continued marching to Restoration Plaza, passing several NYPD “wanted” posters for the baby’s killer. As of July 21, no one had been charged for the homicide.

Combating violence

On the evening of the march, S.O.S. member Takia Gilmore embraced Gardner’s aunt, 23-year-old Shareema Johnson, during a community prayer about the need to curb violence and the devastating effects gun violence has on communities.

“I don’t know what it’s like to lose a nephew, but I know what it’s like to lose someone you love because I’ve lost way too many people to count to gun violence,” Gilmore told Brooklyn Paper. “I’ve been trying to get through it and now that I have family that love me, I know that I can get through it just by being positive, that’s the best thing I can do.”

Shootings and violent crime tend to increase in the summer, but many advocates theorized that mass unemployment, limited activities, and prolonged stay-at-home orders because of the coronavirus outbreak could contribute to the recent spike in gun violence.

City Councilman Robert Cornegy, who represents Bedford-Stuyvesant, echoed those sentiments, saying the community must do more to stop the root causes of violence.

“While one depraved individual pulled the trigger, society is responsible for loading the bullets in that gun,” Cornegy said as S.O.S. tabled outside Raymond Bush Playground.

For his part, Mayor Bill de Blasio announced the “Central Brooklyn Violence Prevention Plan” on July 15, which leans on the work of both cure violence groups like S.O.S. and increased NYPD presence in hotspot neighborhoods to curb violent crime.

The Bedford-Stuyvesant march comes as police, protesters, politicians, and activists debate the causes of the uptick in shootings.

NYPD Commissioner Dermot Shea has pointed to the planned closure of Rikers Island, recently-enacted bail reform, and cuts to the NYPD budget as the primary drivers for the spike in crime.

Others have blamed community deprivation instead, such as poverty and unemployment — and advocate for holistic approaches to help neighborhoods ameliorate those burdens.

In an effort to kickstart the community-based approach, groups like S.O.S. have hit the street to give out literature on gun violence and information on various services that people could utilize to keep them off the streets.

Lawrence Brown, an outreach worker supervisor for S.O.S. Bed-Stuy, spent the night of July 17 trying to engage his neighbors — but bemoaned the lack of more widespread community support.

“There’s a lot of people that believe in what we’re doing. But I’m just saying, with the support of the community, this movement would be even greater,” said Brown, 48. “But if we can connect with one person, that person can connect to two and that can turn into four.”

Dr. Jeffrey Butts, the director of the Research and Evaluation Center at John Jay College of Criminal Justice said that community-based anti-violence initiatives are more effective in the long run than mass incarceration.

“It’s not like a miracle where it just wipes out violence and there are no more shootings, but it can substantially reduce the numbers of violent incidents in that neighborhood,” Butts said.

Butts, who has been studying cure violence programs for years, used the analogy of smoking in meetings going from a normal occurrence to being taboo.

“You can be a 15-year-old walking around with a gun in your pocket and you hear the police commissioner or the mayor say something about shootings and it doesn’t faze you, but if your next-door neighbor … people that you know say, ‘This is not cool, just leave that at home, our neighborhood doesn’t need this,’ and you get those messages consistently, it can start to reset the norms.”

When S.O.S. Bed-Stuy members arrived to Herbert Von King Park to table on July 18, they were met with wafts of barbecue smoke, music from a DJ and the background conversations of families celebrating various milestones.

“Look, people should always be able to enjoy themselves like this,” said Brown.

Overnight between July 18 and 19, at least five people were shot in Brooklyn and one 23-year-old man died after being shot on Nostrand Avenue in Crown Heights, just over a mile from S.O.S.’s table by the park.