The city is ignoring pleas from Brooklyn Bridge neighbors who asked to be spared a lane change that would bring bridge-bound cars closer to their doorstep.

The Department of Transportation rejected a series of demands made by Adams Street residents to modify its revamp plan for the run-up to the borough’s most iconic span, which is supposed to make the area less congested and safer for pedestrians and cyclists. Adams apartment-dwellers-turned-activists, who dread the car traffic coming one lane closer to their buildings, said that the city made a show of listening to their concerns about increased noise while planning to run roughshod over the suggestions the whole time.

“The DOT had their plan all along,” said Peter Liuzzo, a resident of the Concord Village complex, where most of the dissent is coming from. “It’s been a sort of charade as far as listening to public comments.”

The road agency sent a letter to Downtown’s Community Board 2 on March 31, explaining planners’ decision to not incorporate the changes called for when the board conditionally approved the proposal back in February. The city did make some revisions to the plan, called the Brooklyn Bridge Gateway Project, but did not adopt any of the requests, despite strong support for them from the community board.

“We went to bat for Concord Village residents,” said Robert Perris, the panel’s district manager. “But we were unsuccessful in getting the changes the people there thought were most important.”

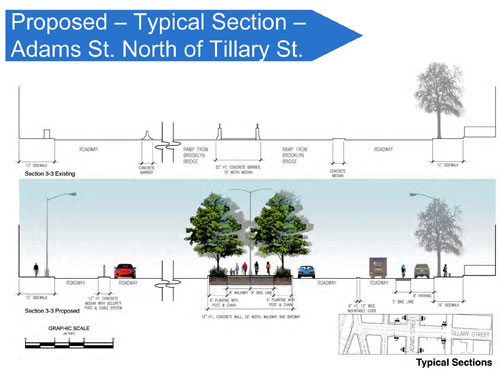

The project will totally redo the pedestrian and bike path leading off the bridge, widening it and replacing the so-called “cattle chute” of cement-and-metal barriers with trees and plants. It also calls for eliminating one of two rows of parked cars on a service road on the Manhattan-bound side of Adams and moving the bridge traffic one lane closer to Concord Village, which some residents say will increase the car noise to unbearable levels.

“It’s so loud already,” said Kamila Kiszko, whose apartment faces Adams Street.

The noise and soot produced by the constant traffic is currently so bad that Kiszko sleeps with a white-noise machine and almost never opens her windows, she said.

“It’s only going to get worse,” she said.

Residents of the apartment complex had asked the bean counters at the transportation department to add a waist-high cement barrier to separate the service road from the bridge entrance. The city’s latest mock-ups omit the barrier, but do replace a seven-inch curb on the block with a two-foot-wide, one-foot-tall planter.

In his letter to the community board, borough roads commissioner Joseph Palmieri said the change was a big step but that anything more would make the bridge approach feel like a Brooklyn-Queens Expressway on-ramp again.

“We have made a significant design change,” he wrote, describing the new solution as a way to create “a more substantial buffer between the service road and the main line without creating a highway-like environment.”

The expansion of the median would mean losing a bike lane on the service road, which the community board was not happy about.

In a response to the city’s decision, Shirley McRae, the board’s chairwoman, wrote that she would rather see the original curb than the city’s latest scheme.

“I do not believe this modification to the median will provide the protection desired by the community,” she wrote. “Furthermore, the modest change in design comes at the expense of the bike lane.”

The board also called on the city to conduct tests to measure the impact of the lane change and the construction noise, but the roads czar said he does not have to, so he won’t.

“The project was found in 2010 to fall into a category of projects exempted from detailed environment review,” Palmieri wrote in the letter.

Some Concord Villagers said they like the project overall, but bristled at the brush-off.

“They’re basically saying, ‘We know better than the community,’ ” said David Cerron, another resident of the complex. “No one’s saying the project shouldn’t go forward. We just want it done responsibly.”

The only recommendation not altered significantly or outright rejected by the city was participation in the Percent for Art Program, which would use one percent of the project’s budget on public artwork.

The first phase of the Gateway project will cost the city an estimated $19.5 million, and is expected to begin by the end of the year.