A developer is seeking to build an affordable housing and commercial hub, including residential towers up to 24-stories tall, at Broadway Junction, a major transit hub in East New York long recognized as blighted and underutilized.

But some long-time residents are sounding an alarm at what they see as a ploy to turn the Junction into another Downtown Brooklyn, especially after what many in the neighborhood characterize as broken promises from the city following the 2016 East New York rezoning.

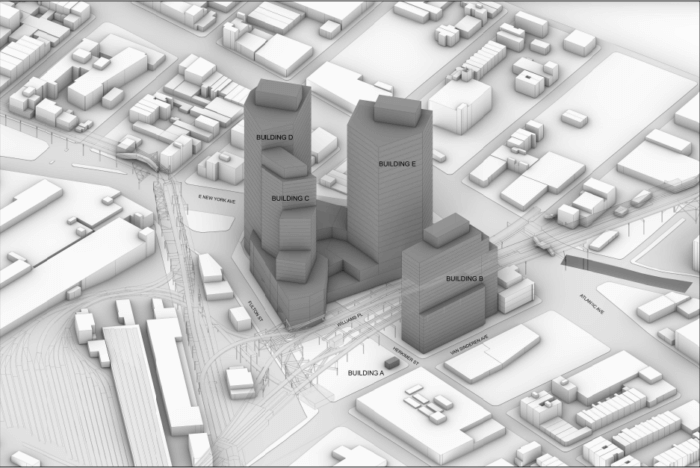

The plan by Brooklyn-based developer Totem Group is in its infancy, but the firm currently envisions constructing four towers, including two residential buildings, housing about 650 new units of below-market-rate housing.

The other two 24-story buildings would hold about 900,000 square feet for offices, plus about 270,000 square feet of retail space and about 90,000 square feet of public community space, according to a presentation by the firm to community residents at a virtual town hall Tuesday night, hosted by new City Councilmember Sandy Nurse.

The rezoning would cover a patch of land bound by Fulton Street to the north, Van Sinderen Avenue to the west, and East New York Avenue to the southeast.

Totem’s plan also calls for demolishing and “demapping” the block of Herkimer Street between Van Sinderen and East New York avenues to make way for the development.

The builders want to take advantage of Broadway Junction’s status as an underutilized transit nucleus — where the A, C, J, Z, and L trains, plus the Long Island Rail Road, all meet, and where Bushwick, Bedford-Stuyvesant, Crown Heights, Brownsville, and East New York all converge — to create a new transit-oriented mega-hub, with housing and new jobs ranging from light manufacturing to high-tech wizardry into the area.

“Brooklyn’s our home, we care about it,” said Tucker Reed, co-founder of Totem, in an interview with Brooklyn Paper. “Any Brooklynite is aware of the fact that Broadway Junction is one of the city’s great transit nodes, and it’s a neighborhood that’s articulated for many years they’d like to see additional investments in jobs and affordable housing.”

Broadway Junction is one of Brooklyn’s busiest subway stations, but almost all of that foot traffic consists of people transferring trains rather than entering or exiting the station, especially as compared to similar outer-borough hubs like Atlantic Terminal and Jamaica Center.

The parcel that Totem wants to develop currently consists of industrial uses like chop shops, used car dealers, and an MTA maintenance facility, along with parking lots, empty lots, the Calvary Unified Free Will Baptist Church, a hotel, and lots of land devoted to supporting the giant, labyrinthine above-and-underground subway complex.

Totem already owns a decent chunk of the land, though not all of it.

Residents, advocates, and elected officials have long complained that the area is blighted and underutilized, and numerous studies have been commissioned over the past decade to consider ways to redevelop the Junction, most recently by the Economic Development Corporation in 2019, at the behest of then-Borough President and now-Mayor Eric Adams, which found that redeveloping the area presented a “unique opportunity to bring education, workforce training, and quality employment opportunities closer to” neighborhoods with higher unemployment and lower incomes than the citywide average.

The area around the station also sees chronic underinvestment, with one of the most frequent complaints being poor lighting that makes the surroundings unsafe at night. Despite the general agreement on the need to redevelop the area, no such initiatives have been undertaken.

“It’s okay for us to be honest: the state of Broadway Junction is not okay for our people,” Nurse said at the town hall. “There is lead paint falling from the tracks. The sidewalks are really challenging for our seniors and mobility-impaired folks. There are abandoned vehicles and litter and illegal dumping.”

“It’s really important to remember that our communities have all deserved equitable investments in our public infrastructure and there is not a single reason why the city could not have, and cannot now, invest in high-quality public infrastructure for the third-busiest transportation hub in the borough.”

Reed and his fellow Totem principal, Vivian Liao, took pains at the town hall meeting to note that the process was only in its amniotic stages, with the start of the lengthy Uniform Land Use Review Procedure still years away, at best, and said that they’re open to a slew of ideas derived from community input, like a trade school or a formal space for local street vendors.

The firm touts itself as a socially-conscious developer driven by the interests of the community, citing its proposed 17-story building at 1045 Atlantic Avenue, recently approved by the City Council, that would be the first all-electric-powered residential building in central Brooklyn, for one.

The firm is seeking to develop all 650 residential units to be permanently affordable, ideally at an area median income that matches the surrounding community (asked by a resident if they would target an AMI of about 30-35 percent, Reed said those were among the AMI levels they were targeting), with no market-rate housing; Reed told Brooklyn Paper that it would have to win city approval and funding to do so.

But many participants in the town hall were not ready to trust Totem’s claims, nor those of the developer’s allies.

“There’s a high level of distrust of government due to neglect,” said Bill Wilkins, president of the East New York Local Development Corporation and a supporter of the project, in an interview with Brooklyn Paper. “There’s a high degree of distrust towards developers. And that has to do with the lack of capital investment coming into East New York for decades.”

Also at play are broken promises from the city in the wake of the 2016 rezoning of East New York, including a slow pace of development of new affordable homes and, even more saliently, the promise of 3,900 new manufacturing jobs in the rezoned industrial business zone that have not come close to fruition.

Wilkins — who lives near the Junction and uses the subway stop daily — told Brooklyn Paper that the failure to produce 3,900 jobs likely stemmed from the “bifurcation” of the 2016 rezoning to exclude Broadway Junction, the area he believes has the most potential as an employment hub.

At the town hall, he said the area as currently constituted is “blighted, distressed, underdeveloped, and underutilized,” and is in need of a “revolutionary and evolutionary transformation that reflects community-driven development.”

Reed, for his part, said that while he can’t force employers to occupy his new towers, he’s open to working with the community on ideas on attracting new jobs that would hire locally.

“I don’t claim that we have all the answers for how we’re gonna convince a significant number of employers to move here,” he said. “But we have a lot of ideas about how.”

But to those residents who remember the broken promises of the East New York rezoning, and other rezonings like Williamsburg and Downtown Brooklyn, a developer’s promises are worth essentially bupkes.

“You’re giving us promises, you’re not giving us anything definitive. It never works out in favor of the community,” said Debra Ack, a 20-year neighborhood resident opposed to the rezoning, who says she doesn’t want 24-story towers in the neighborhood, in an interview with Brooklyn Paper. “I don’t want to see East New York turned into Downtown Brooklyn. People in Downtown Brooklyn lost homes, they were forced to sell. The times are changing, we do need to evolve, but there’s a limit to it.”

Ack, a member of the East New York Community Land Trust, says she would rather see the land be developed as recreational space, like ice skating, pools, a skatepark, or senior centers.

“We’d love to see more recreational spaces for our youth,” she said. “Our youth really need somewhere to go.”

Although many are worried about the specter of displacement, one major difference would distinguish the Broadway Junction process from the 2016 rezoning: city law now requires all major rezonings to undergo a “racial impact study” to determine how a rezoning would impact the ethnic makeup of an area.

A City Council representative said that the study, which would be effective for any rezoning started after June of this year, includes a tool to measure displacement, a major sticking point from the last East New York rezoning.

A racial impact study was commissioned for the rezoning of Gowanus, which after years of languishing won city approval last year: the study found that the rezoning would make that neighborhood, named for the noxious canal that runs through it, more diverse. But Gowanus is a whiter and wealthier neighborhood than East New York; diversification in one area can be, and often is, seen as displacement and gentrification in others.

“We see this as not a plan for us. This is a plan to remove us,” said Brother Paul Muhammad, a member of Community Board 5, at the town hall. “If you don’t plan with us, you plan to build on us, not with us. So we say no to it.”

With ULURP still eons away, Nurse said that the developer will need to provide more than just promises to win her support. And beyond that, she and others — like Borough President Antonio Reynoso, who was also present at the meeting — decried the format of the current land use process as dooming an area like Broadway Junction to blight unless a developer can come in and seek a profit.

“We should not have to wait for developers or for our city to make investments,” Nurse said. “And it’s appalling how long the city has allowed Broadway Junction to be in the state it is.”

This article has been updated to provide greater clarity on income bands for housing that Totem is targeting for its development.