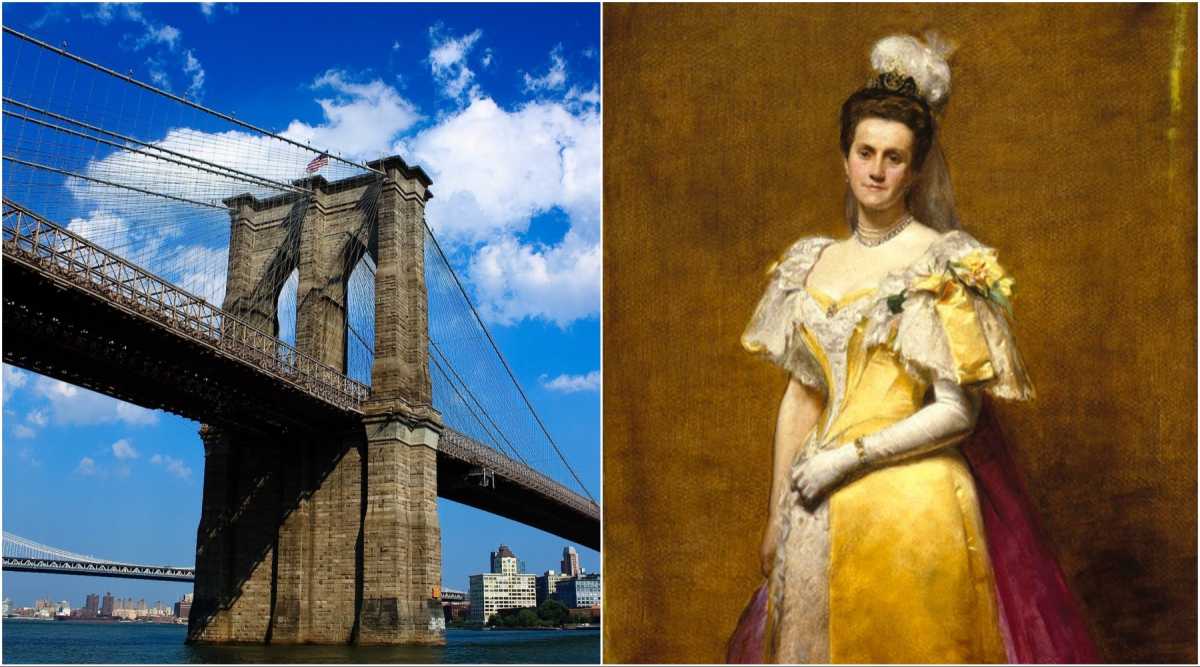

Emily Warren Roebling remains one of the most influential women in the history of New York City after she contributed immensely to the design and construction of the Brooklyn Bridge in 1883. Despite the bridge being one of the most photographed sites in the world, few know the story behind its construction or the woman responsible for it.

Roebling was born on Sept. 23, 1843 in Cold Spring, NY and was the second-youngest of 12 children. Her family was relatively affluent and provided her with the most appropriate advanced education available at the time for young women. Her interests in her studies were facilitated and supported by her older brother, the Major General Gouverneur K. Warren, who served as a U.S. army general during the American Civil War and participated in the infamous Battle of Gettysburg. He was also remembered as “the hero of Little Round Top.”

In addition to his military career, Warren was also a civil engineer and it was through him that his sister met her husband Washington A. Roebling.

Prior to the war, Washington had assisted his father on the construction of the Sixth Street Bridge — also known as the Roberto Clemente Bridge — in downtown Pittsburgh.

By the time the war had ended in 1865, Washington and Emily had married and departed on their honeymoon to Europe, not just to relax and celebrate their union, but to learn more about the construction and design of caissons which are used to help construct the foundations of bridges.

Upon their return home, Washington’s father had begun design on the Brooklyn Bridge, a massive engineering undertaking which would not only connect Manhattan and Brooklyn but would be the longest suspension bridge in the world at the time once completed.

Prior to the bridge’s completion, people depended entirely on ferry transportation on the East River to travel from Manhattan to Brooklyn, which were also two independent cities at the time. The ferries were unreliable and often travelers were left stranded if inclement weather impacted traveling or if the river was frozen.

Construction for the bridge began in 1870, with Washington taking over his father’s role as chief engineer of the project after he died following a tetanus infection. However, the work was incredibly dangerous and Washington himself infamously sustained incredible injuries one day working inside the bridge’s caissons.

Caissons operated at the time with compressed air pumped inside the structures to allow workers to operate despite being anchored to the river’s bedrock underwater.

One worker described the frightful experience saying, “In five minutes the sweat was pouring from us, and all the while we were standing in icy water that was only kept from rising by the terrific pressure. No wonder the headaches were blinding.”

In 1870, a fire broke out inside one of the caissons and Washington worked to extinguish it but due to the immense amount of pressurized air and the prolonged time he spent in the caisson, he suffered from debilitating decompression sickness or “the bends” which left him completely immobilized for the rest of his life.

Following this dramatic and potentially devastating loss of the project’s lead engineer, Emily was forced not only to care for her ailing husband, but to continue his efforts to complete the bridge.

“She took on everything and became like the default engineer because he wasn’t able to go out and physically be there,” Assistant Director for Collections and Public Services at the Center for Brooklyn History, Natiba Guy-Clement told Brooklyn Paper. “She also had to go out and speak on his behalf.”

The other heads of the project wanted to remove Washington from his role completely, Guy-Clement said, but Emily went to the Society of Engineers and presented her husband’s remarks herself.

“Back then they weren’t taking women seriously, but she had such a commanding presence and got so much respect when she went out and spoke to them about why he should continue doing the work that they listened to her and they kept him on the project, essentially keeping both of them,” she said.

Following her husband’s accident, Emily relayed information from Washington to his engineering assistants and reported back to him on the progress of the work. In doing so, she herself became extremely well-versed in engineering techniques and bridge construction, with an extensive knowledge in material strength, stress analysis, cable construction and more.

“[Washington] would sit at his window and use a telescope to see the progression of how the bridge was being built, but Emily really served as both his eyes, ears and mouth during the construction,” Guy-Clement said. “She did a lot of negotiating about the materials that were being used, did a lot of going back and forth between talking to him and talking to the people that were physically making the bridge.”

This partnership continued from 1870 when they took over the bridge construction’s responsibilities through the bridge’s official opening ceremony on May 24, 1883.

While the bridge was being built, Emily’s involvement was well known to those also directly contributing to the construction as well, however the general public remained largely oblivious that the construction of the longest suspension bridge in the world had been possible because of a woman.

On the celebration of the Brooklyn Bridge’s opening, then-Congress Member Abram Stevens Hewitt took time to acknowledge not only Emily’s immense sacrifice tending to her husband, but also her monumental achievements with the bridge’s construction.

“The name of Emily Warren Roebling will … be inseparably associated with all that is admirable in human nature and all that is wonderful in the constructive world of art,” Hewitt said, and that the bridge would serve as “an everlasting monument to the sacrificing devotion of a woman and of her capacity for that higher education from which she has been too long disbarred.”

Following the bridge’s completion, Roebling became one of the first people to cross the bridge, carrying a rooster in her lap as a symbol of prosperity and progress.

Following the bridge’s completion, Emily was an active participant in the women’s suffrage movement and in her community before dying of stomach cancer in 1903.

Despite her immense accomplishments, Emily was not immediately recognized for her achievements and wasn’t formally recognized until a plaque was erected on the bridge in her honor in 1950. Now however, it seems her legacy is emerging. In 2021, the final part of Brooklyn Bridge Park, named Emily Warren Roebling Plaza opened just below the bridge.

“The only thing I could find about her before the bridge was in a society page talking about an event she went to,” Guy-Clement said. “And you have to remember when you’re searching for these things, you can’t search ‘Emily Roebling’, they wrote about her as ‘Mrs. Washington A. Roebling’. I think people didn’t talk about her [involvement with the bridge], it was not something that was known within the general public — they probably had no clue. I’m picturing people saying ‘I’m not going to cross this bridge since it was built by a woman,’ just very narrow-minded and silly thinking at the time.”

Fifteen years after the bridge was built, Emily wrote a letter to her son voicing her frustration at the lack of acknowledgment, saying “I have more brains, common sense and know-how generally than any two engineers, civil or uncivil, and but for me the Brooklyn Bridge would never have had the name Roebling in any way connected with it!”