In the ten years since Hurricane Sandy, the question of how to protect New York City’s coastal neighborhoods from future storms has loomed large.

Brooklyn alone has 131 miles of shoreline, and recent storms have brought with them enormous storm surges and flooding from Coney Island to Greenpoint.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers has a $52 billion idea — a complex system of sea walls, flood gates, levees, and more — that would stand against the floodwaters.

In northern Brooklyn and parts of southern Queens, that could mean new concrete walls standing between the community and the city’s waterways.

But the plan is not final, emphasized Army Corps project manager Bryce W. Wisemiller at a Feb. 23 town hall meeting in Greenpoint, and the Army Corps will be incorporating as much public feedback as possible as it refines its plans.

“Let’s be clear that these are preliminary proposals that have yet to be refined and developed,” said U.S. Rep. Nydia Velázquez, who hosted the meeting. “Nothing proceeds — from study to construction — without local buy-in and support.”

The government and the community “must get it right,” Velázquez said, adding that she has worked with the Army Corps for decades — and that Wisemiller has always been an “honest broker.”

Breaking down the Army Corps proposal

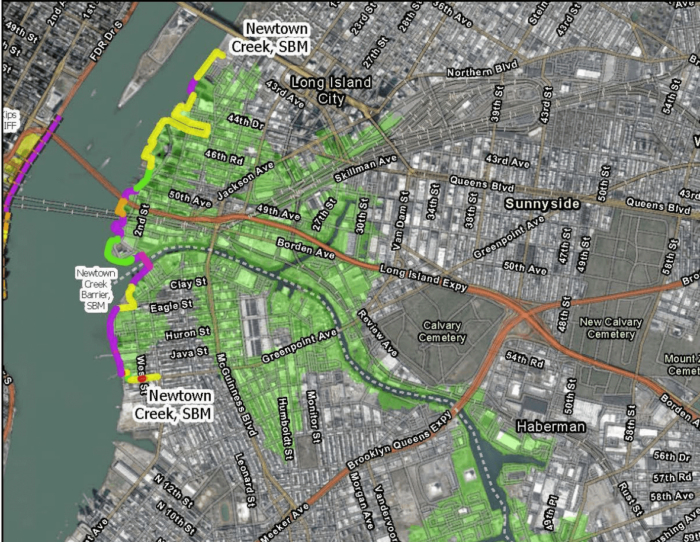

The Army Corps has proposed building a series of sea walls, flood walls, and levees along the shoreline from Greenpoint Avenue in Greenpoint to 43rd Avenue in Astoria, and a flood gate in Newtown Creek.

The proposal is the result of years of intensive study of the area, Wisemiller said, and takes into account rainfall, groundwater rise, and more – but the Army Corps is particularly focused on the impacts of storm surge in a 100-year storm.

Aptly named, 100-year storms have a 1% chance of occurring in any given year – but climate change has caused them to occur much more frequently. In 2021, the city weathered two 100-year storms in the span of two months.

“Some refer to our view on storm surge as being somewhat myopic, but that is the impact that has caused tens of billions of dollars in damage, and has the greatest life safety threat of all those risks,” Wisemiller said. “That has been a primary focus of the study so far.”

If storm surge is damaging now, it’s only going to get worse, he warned — sea-level rise appears set to meet worst-case projections, and the waters around New York City are expected to rise eight feet over the next 100 years.

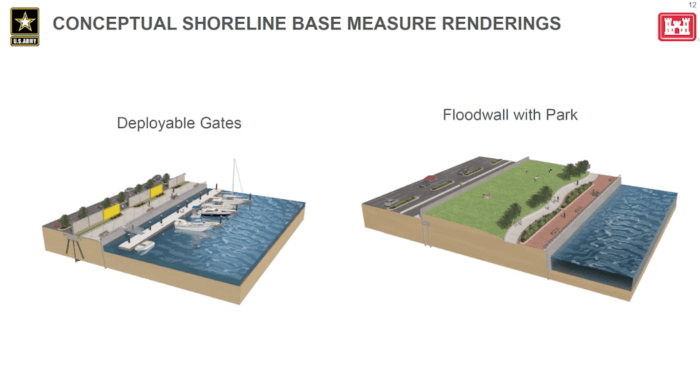

Renderings show a roughly 15-foot-high sea wall erected along the East River in Greenpoint. The permanent high wall blocks access to and the view of the river, and would be in place at all times – unlike the temporary, moveable flood walls proposed for other neighborhoods.

Corps maps show elevated levees circling Hunters Point South Park in Long Island City across Newtown Creek, and a network of sea walls, levees, and elevated walkways stretching up the coast, through the Gantry and past the iconic neon Pepsi-Cola sign.

Everything is subject to change, Wisemiller said. Infrastructure could be moved around or swapped for more favorable alternatives — like a flood wall built into a park, or a raised pedestrian walkway so New Yorkers could still enjoy the water.

Not included in the proposals, but certainly expected to be part of the solution are less-intense measures like flood proofing existing buildings and adding green infrastructure like green roofs and rain gardens.

A key part of the proposal is the storm surge barrier and flood gate at the mouth of Newtown Creek, where it meets the East River. Day-to-day, the gate would be open, allowing normal maritime traffic and water flow — but would close during big storms to keep storm surge from the river from flooding the creek and the neighborhoods on its banks.

The creek also poses significant challenges — it’s a heavily-contaminated Superfund site, and cleanup isn’t expected to begin until 2032, and may not be completed for decades.

Only the mouth of the creek would need to be cleaned up for the Army Corps to install the gate and barriers, according to Wisemiller. Stephanie Vaughn, project manager at the federal Environmental Protection Agency, said the cleanup schedule may coincide with the construction of the flood infrastructure, based on current timelines.

Community concerns: building in a Superfund, walling off parks, and more

Local activists and experts have raised concerns about the impact of meddling with an active Superfund site, especially since they’ve been waiting so long for Newtown Creek to be cleaned up — it was added to the Superfund list in 2010, and there’s been very little action since then.

“The exchange between Newtown Creek and the East River is incredibly vital to the health and the remediation of Newtown Creek,” said Willis Elkins, executive director of the Newtown Creek Alliance. “We have strong current flows that are coming in and out twice a day, and everything that’s going to inhibit the flow of that water is going to have, in our opinion, strong impacts on the water quality of Newtown Creek and how a Superfund remediation is going to happen.”

The Alliance is one of ten local environmental groups working together as the “NYC and NJ Urban Tributaries Working Group” to oppose the plan. In a Feb. 23 letter submitted as public comment, the Working Group said the proposal has too narrow a focus, and will not provide wide-ranging enough protections.

The Creek isn’t the only point of concern for locals. Steve Chesler, on behalf of Brooklyn Community Board 1, said northern Brooklynites have fought hard for their open space — and are still waiting for the city to come through on some of its promises.

“We have a huge issue with the idea of walling it off,” Chesler said of the waterfront.

While the wall would block some public open spaces, it leaves others unprotected, Chesler added — Bushwick Inlet Park is south of the proposed walls and floods badly during storms, as does McCarren Park further inland.

Dewey Thompson, of North Brooklyn Neighbors, echoed those worries about unprotected parts of Williamsburg and Greenpoint. Newtown Creek isn’t the only toxic site in the area, he said — there’s the old NuHart Plastics site, a state superfund; plus the Meeker Avenue Plume and the recently-remediated manufactured gas plant at 50 Kent Avenue.

“All those areas are also under threat of inundation by floodwaters, and the impact of having floodwaters carry contaminants through the neighborhood, I think, has to be addressed,” Thompson said.

Council Member Julie Won, who represents parts of western Queens including Astoria and Long Island City, said she’s not impressed by the proposals for the outer boroughs.

“We want to see the flip-up barriers that are being invested in for Manhattan, but we’re not seeing the same investment in Queens, or in Brooklyn,” Won said, referring to temporary sea walls proposed for Manhattan. “We don’t want to see the sea wall, we want to see the water from time to time.”

There is still plenty of time left before any decisions are finalized, and construction won’t begin for years, Wisemiller said. The public comment period closes on March 7, and the Army Corps is expected to continue their study of possible solutions until at least June 2024.

After that, they’ll submit it for congressional approval. If the plan gets a thumbs-up, it will enter a six-year design phase — then construction can begin, and is expected to last up to 14 years.

“The bottom line of what we’re really trying to communicate is this neighborhood has unaddressed severe coastal storm risk,” Wisemiller said. “ We need to do something. Maybe the sea wall, maybe the flood wall, maybe the location needs to change. The storm surge that can hit this area is substantial, and we need to prepare for it now.”

The public comment period for the USACE’s proposed plan is open until March 7, 2023. Learn more and submit your comment here.