Developers of a massive affordable housing complex along the Gowanus Canal will have to deal with a century’s worth of harmful pollution before they can safely house people, a federal environmental guru warned.

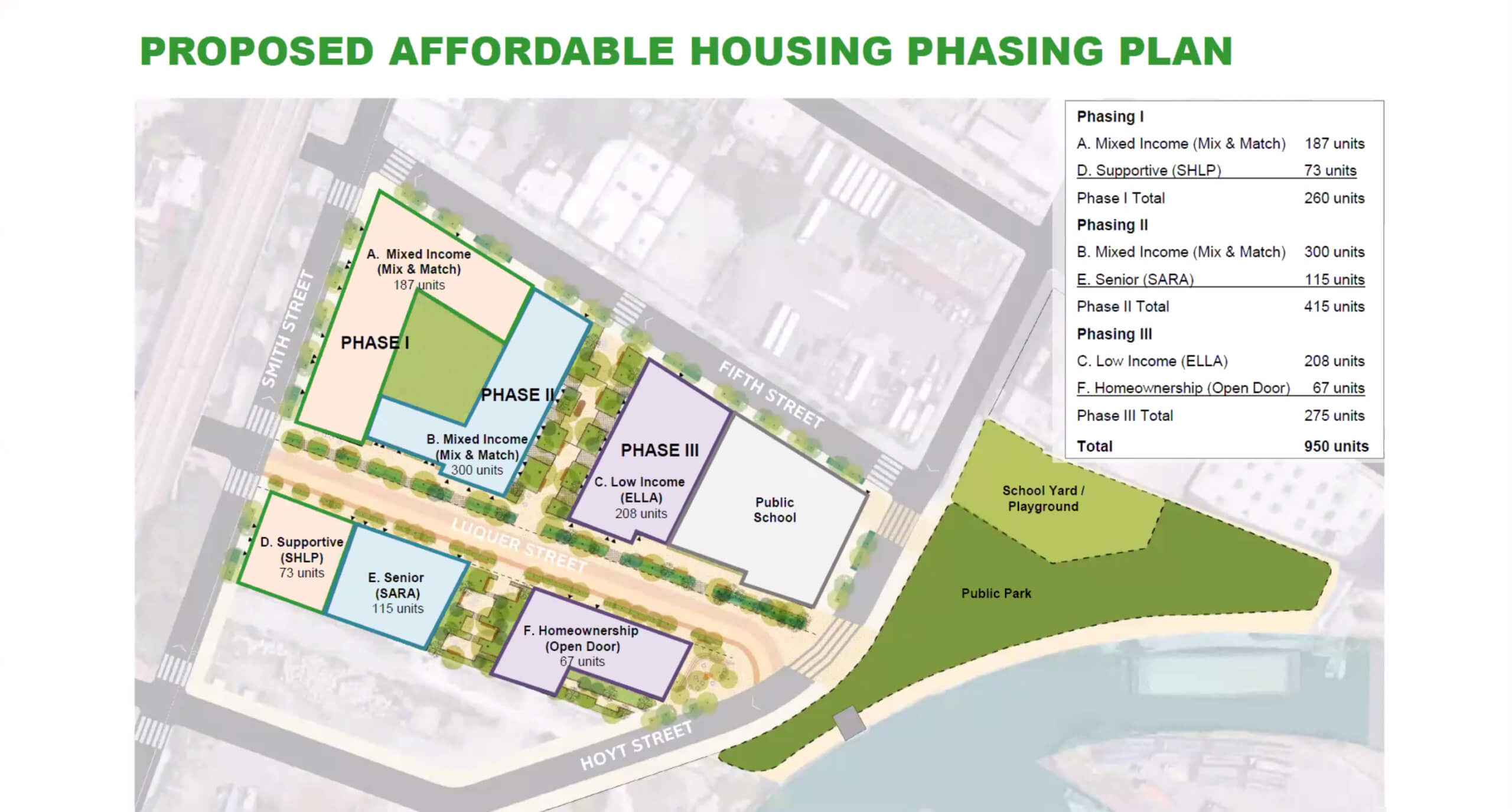

The project near Smith and Fifth streets, known as Gowanus Green, will house nearly 1,000 below-market-rate apartments and a new public school building — but buried chemical remains from a former gas plant at the site could seep into the planned structure and endanger the health of the building’s occupants, unless developers and government officials install the right protections, an Environmental Protection Agency rep said.

“If you put a structure like a school or a building, those compounds that are 8, 10, 15 feet down, they will volatilize,” said Christos Tsiamis, who is managing the Gowanus Superfund cleanup, at a Dec. 1 community meeting. “It might be in five years, it might be in 10 years, they will find a path and they will come inside the enclosed structure and they will build up.”

The Gowanus Green project has been in the works in different iterations since the Michael Bloomberg administration, and is now part of the larger neighborhood rezoning, which is due to go into public review in January.

The ground beneath Public Place, the name of the site where the planned complex is located, is heavily contaminated with coal tar — a toxic byproduct of gas production, which happened at the site for 100 years until the gas plant closed down in the 1960s and the land was seized by the city.

State environmental officials have found the dark viscous material, known locally as “black mayonnaise,” at depths of more than 150 feet at Public Place, and digging up the ground for development could release toxins such as Naphthalene, a compound used in mothballs that can cause irritation and lead to nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea when inhaled, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Tsiamis noted that other more volatile toxins also found in coal tar are benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, and xylene — known collectively as BTEX — some of which have been linked with forms of cancer such as Leukemia, according to the National Institutes of Health.

National Grid is currently working to address some of the pollution through the state Department of Environmental Conservation’s Brownfield Cleanup Program, but the project is aimed more toward containment than a full-scale cleanup.

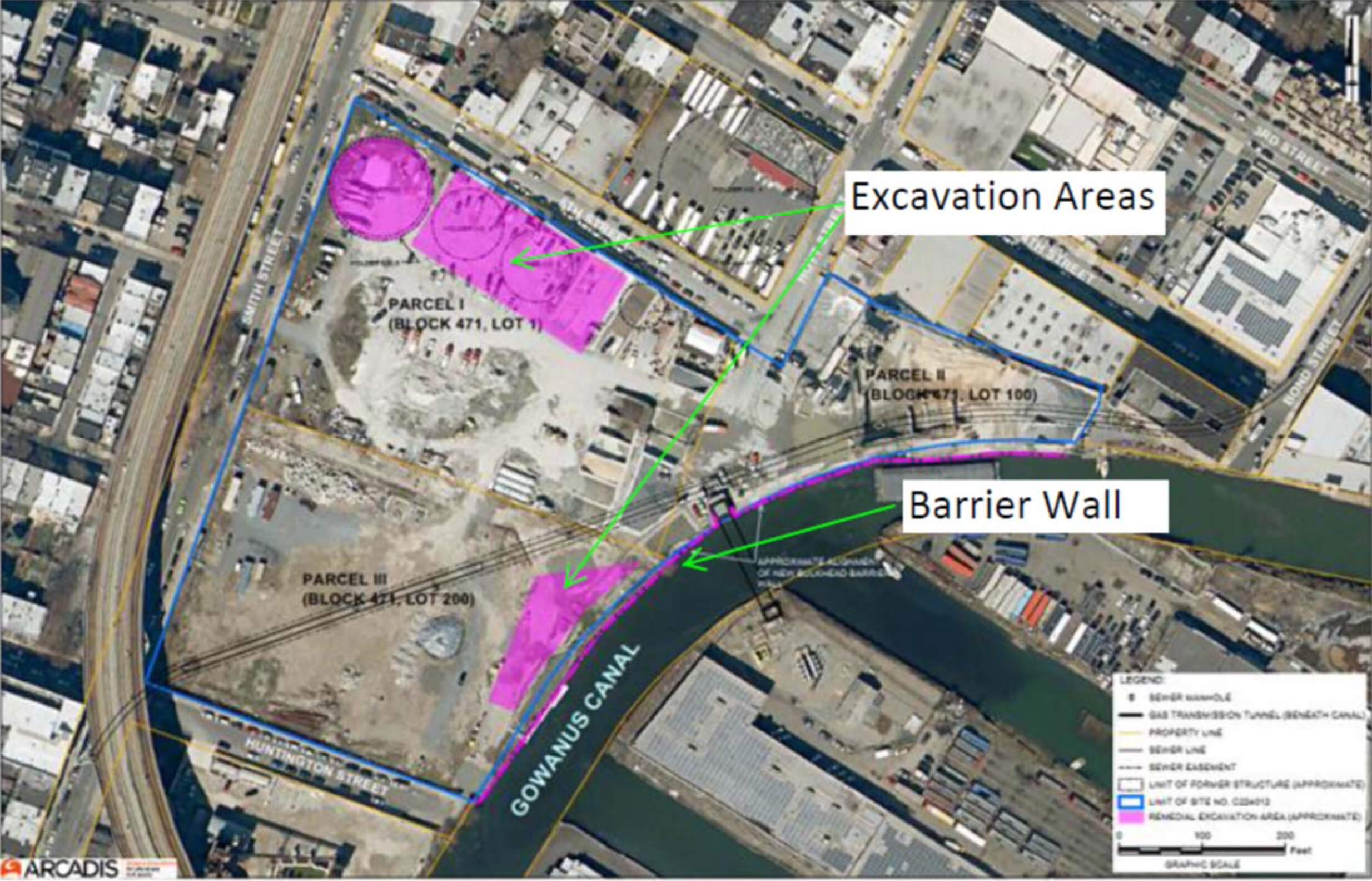

The utility’s contractors will excavate up to 22 feet around the old holding tanks at the northwest corner of the site where pollution is worst, before adding in clean fill along with 2 feet clean top soil across the site. Contractors will also install a bulkhead along the adjacent canal to keep the toxins from seeping into the waterway. That project is slated to wrap next summer.

The pollution hotspots where the former gas tanks were situated are marked in pink at the northern end of the site.New York State Department of Environmental Conservation

The pollution hotspots where the former gas tanks were situated are marked in pink at the northern end of the site.New York State Department of Environmental Conservation

The city and developers’s plans show that the planned school and some of the lowest-priced affordable units are slated to go at the corner of Fifth and Hoyt streets, right next to some of the most polluted sections of the site that once housed gas tanks.

City officials briefly mentioned that additional remedies pre-development will be necessary at a November presentation about the Gowanus Green project, but Tsiamis said the measures will be no small task.

To keep the poisonous materials from seeping into the buildings, developers will have to install a vapor protection system to trap toxic materials below ground, he said.

A nasty legacy of the polluted soil will be so-called coal tar extraction wells, which will likely be installed below the area of a proposed 1.5-acre waterfront park adjacent to the affordable housing complex, because the viscous liquid will move down the slope and accumulate at the waterfront bulkhead.

The black mayo will have to be sucked out of those capture facilities for years to come — which, unless it’s sealed off, can be a smelly and messy affair for the people living and going to school there, said Tsiamis.

“From my experience standing around those wells when they are pumped is not a pleasant [experience],” he said. “I don’t think children — or even adults — should be playing around when this is happening. Pumping of the tar will occur certainly for our lifetimes and so folks should be given [information] as to how this is going to be practiced.”

The city and developers also touted several mechanisms for capturing stormwater at Gowanus Green, including so-called bio-swales, rain gardens, green roofs, and retention tanks — the latter of which will become more necessary, as greater amounts of runoff will gather due to the hard surfaces of the development, Tsiamis said.

“Remember when we were looking at Public Place it was an open field, now you have a lot of impermeable surfaces,” he said. “What they will have to do if they do further remediation, they will have to size up the treatment units.”

The development will also separate its sewage from the stormwater, which will likely flow into the Bond-Lorraine sewer pipe that runs across the site under the proposed park. But Tsiamis cautioned that the old brick pipe is currently constricted by blockages and that the city should make sure the additional flows of waste don’t overburden the tube.

“I think it will be problematic, they have to look into that,” he said. “So that nobody finds themselves before a surprise, some things should be discussed.”

The city agencies in charge of overseeing the project, the Department of Housing and Preservation and the Department of City Planning, did not immediately return a request for comment.