Ten years ago this Saturday, Oct. 29, Superstorm Sandy slammed into the southern coast of New Jersey and rolled north to New York City, where it inundated the five boroughs with historic floods of up to 14 feet above sea level, knocked out electricity for millions, and caused at least $19 billion in damage.

Though Sandy had been downgraded to a tropical storm by the time it arrived in the city, a combination of factors — high tides, competing weather patterns that stalled out the storm and allowed it to gather strength, and the sheer size of the system — meant it was the most destructive storm to arrive in New York City in recent history.

Coastal Brooklyn was particularly hard-hit. High winds and flooding devastated the thriving Coney Island amusement district and the surrounding neighborhoods. Red Hook, surrounded by three bodies of water — the Gowanus Bay, Buttermilk Channel, and Upper Bay — was flooded on all sides.

Two different federal Superfund sites — the Gowanus Canal in Gowanus and Newtown Creek in Greenpoint — flooded their respective neighborhoods with questionably-safe water. The famous Jane’s Carousel in DUMBO was surrounded by water as the East River swept over its banks.

Days after the storm, a 270-foot U.S. Coast Guard vessel kitted out with food, gasoline, and medical supplies docked near Bay Ridge to facilitate the delivery of supplies to residents.

When the shock of the floods, the power outages, and the rain receded, the real impact of the storm set in — and, ten years and billions of dollars later, the city is still trying to recover — and make itself more resilient to future storms.

A long legacy for public housing

The city’s New York City Housing Authority developments were particularly hard-hit. At least 38 ground-floor apartments between Coney Island’s three public housing complexes were destroyed by the storm, and the building’s roofs, playgrounds, boiler systems, and more were damaged. Gowanus Houses lost electricity for at least eleven days, and, as outages stretched out in some buildings, residents said they were receiving few updates from state and federal officials.

Red Hook Houses, the city’s largest public housing development, lost heat, running water, and electricity. Some tenants didn’t get electricity back until mid-November, and community organizations like the Red Hook Initiative volunteered their time and gathered resources to make sure residents were fed, clothed, and warm.

Despite millions of dollars in recovery funding from the Federal Emergency Management Agency, repairs at many NYCHA complexes still aren’t done. Five years after the storm, Red Hook Houses was still plagued by mold, falling ceilings, and electrical issues.

In 2017, construction began on a long-awaited resiliency project at Red Hook Houses. The project is slated to include new roofs, sump pumps, and more, as well as additional infrastructure like boilers that would be raised above flood levels.

Four years after work started, Red Hook Houses residents said contractors had made life in the complex “unbearable” as they worked on the behind-schedule project tearing up trees, fencing off communal spaces, and removing benches.

Meanwhile, in Coney Island, work is still underway at six out of nine Sandy-affected sites, according to NYCHA’s Sandy Transparency Map. Across all 35 NYCHA complexes damaged by the storm, the agency has installed 185 new roofs, 72 new boilers, and 8 new, operational boiler systems, according to a fall 2022 update.

The construction has brought additional headaches to some of Coney Island’s public housing residents. At O’Dwyer Gardens, where work is expected to wrap up in late 2023, a contractor accidentally broke a gas line while they worked to install a new boiler — knocking out cooking gas for hundreds.

Public spaces struggle to recover

Brooklyn’s public spaces were also smacked by the storm. The Coney Island Library was practically washed away — it was the hardest-hit of any Brooklyn Public Library branch, a BPL spox told Brooklyn Paper at the time.

The library was shuttered for nearly a year as a $2 million renovation replaced technology, floors, plumbing, and, of course, books. Last year, as part of a $4 million effort to turn four south Brooklyn libraries into disaster hubs, the Coney Island Library debuted new solar-powered backup systems that could keep it up and running in case of future power outages.

Branches in Gerritsen Beach, Mill Basin, and Sheepshead Bay received similar treatments.

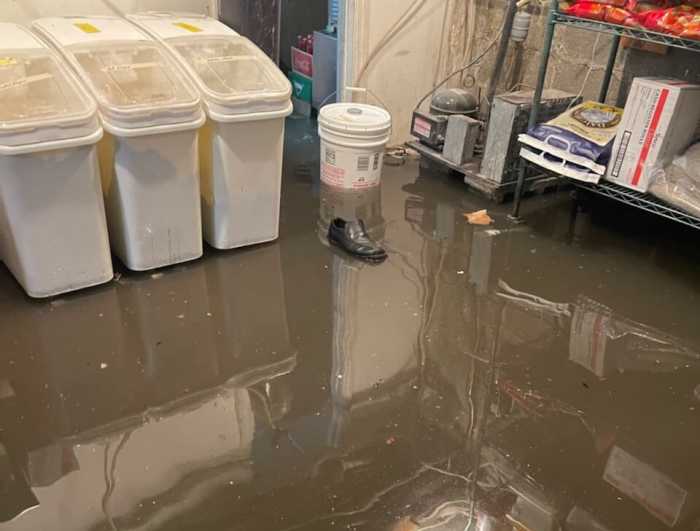

The Red Hook Recreation Center was also damaged during the storm — flooding wrecked the center’s boiler, which was not replaced until 2014, when a $763,000 reconstruction was finished over-budget and behind schedule. Last fall, the new boiler was damaged by Hurricane Ida — and the center was once again closed before a replacement could be found.

Elsewhere, arts venues — especially those in low-lying neighborhoods like Gowanus — filled with water. The New York Aquarium in Coney Island only fully reopened last summer, after working slowly to restore its facilities to pre-Sandy conditions.

Homes and businesses all over Coney Island were devastated by the storm — the streets were filled with water and sand — though local pols and business owners celebrated the nabe’s recovery from destruction just a month and a half after Sandy.

Help for home-and-businessowners

At the core of Sandy recovery were longtime locals who lived and worked in Brooklyn. In 2014, some businessowners told Brooklyn Paper they felt left out of the federal small business recovery grant program, saying the money was “almost impossible to get.”

A recovery grant program for homeowners was similarly criticized — a 2015 audit of the “Build it Back Sandy” program lambasted it as “a case study in dysfunction. Brooklyn homeowners said they struggled to get in touch with helpful representatives, and, even when they could, the program guidelines changed so frequently it was impossible to keep up.

In 2012, many home and businessowners did not have adequate flood insurance — or any flood insurance at all, according to a city report on Sandy, and policies have only gotten more expensive and difficult to get.

A 2019 investigation by news outlet The City found that eight-in-ten properties in flood-prone areas don’t have insurance. Just 14% of homeowners in Canarsie had flood insurance, the investigation found.

Incoming resiliency measures inspired by Superstorm Sandy

Superstorm Sandy was an outlier and a warning – more intense storms are coming to New York City as climate change worsens. Last year, Hurricane Ida dumped up to six inches of rain on the borough, flooding homes, businesses, and even parks. The storm brought memories of Sandy to the forefront for many Brooklynites as they dealt with significant damage to their homes and businesses and reckoned with a lack of resiliency infrastructure.

But changes are coming. Last month, the U.S. Coast Guard announced it had tentatively settled on a $52 billion resiliency plan for the entire city — which would bring sea gates, flood walls, and more to coastal areas.

Over the course of about 15 years starting in 2030, the pricey plan would encircle vulnerable parts of the Jamaica Bay and Coney Island with flood-mitigation structures, add flood gates to the Gowanus Canal and Newtown Creek, and more. In Red Hook, where design for the Red Hook Coastal Resiliency Project is nearly done, the city plans to add deployable flood walls and even raise some streets higher than projected flood levels.

The new Ruth Bader Ginsburg Hospital — on the campus of the former Coney Island Hospital — opened this month with a whole host of flood-resiliency measures funded by a $923 million FEMA grant.

Together, government officials and residents hope the measures will protect the city from future floods and storms — either by preventing flooding or ensuring that infrastructure can stand up to the waters when they come.

“Ten years ago this week, New Yorkers saw what a storm supercharged by climate change can do to a city,” Mayor Eric Adams said at the Oct. 26 unveiling of a new $522 million East River resiliency project in Manhattan. “Flooded subways. A week long blackout downtown. Riding downtown, seeing this city in darkness, both [with the] lights off and just the spirit of the people were devastated. Thousands of New Yorkers without homes, without water, without utilities. Our buildings and property [were] damaged. And most importantly, 44 New Yorkers lost their lives.”

The project, dubbed the Brooklyn Bridge-Montgomery Coastal Resilience (BMCR) project, would add infrastructure intended to mitigate sea-level rise and resist storm surges along the Two Bridges waterfront. Those mitigation measures would include several flood walls and deployable flip-up barriers designed to protect against a 100-year coastal storm surge and account for sea-level rise by the year 2050.

“Once this is in place, moveable flood walls will protect the two bridges neighborhood of Manhattan when needed, while continuing to preserve views and access to the waterfront when they are not being utilized,” the mayor said. “We understand that we will not be imprisoned to the storm, but we must be prepared for the storm.”

Adams also called on the the federal government to fund resiliency projects in Coney Island and Bushwick Inlet Park.

Additional reporting by Ethan Stark-Miller