State Sen. Daniel Squadron unveiled a radical new proposal for the underfunded Brooklyn Bridge Park development that would eliminate hundreds of planned condos from the park and, instead, use property taxes from nearby landowners to pay for the controversial park project’s upkeep — but several critics immediately punched holes in the plan.

Squadron’s initiative would siphon off some of the taxes on any rezoned property within .4 miles of the planned 85-acre park along the Brooklyn Heights and DUMBO waterfront — some of the very landowners who are expected to see their property values rise due to their proximity to the proposed 1.3 mile-long park.

He said his plan could rake in $20 million over five years, though it’s largely reliant on being in place before the city rezones DUMBO, a lengthy process that is underway.

Instead of entering the city’s general fund, those taxes would be restricted to paying for the park’s annual maintenance, which is estimated to be around $16 million.

The freshman senator said such a plan would eliminate hundreds of proposed luxury condos from inside the park’s footprint, though his plans still include a 225-bed hotel and shopping in the historic Empire Stores warehouse, features that are in the official state plans for the controversial park-and-condo project as well. Squadron (D–Brooklyn Heights) described these as “appropriate, though not ideal, uses.”

The park’s current annual maintenance budget would rise further under Squadron, who is also calling for design changes that would include an enclosed bubble for seasonal sports, a swimming pool moored in the East River, an arts facility and an ice-skating rink. He said these features are “eminently affordable.”

“We’re talking about minimal increases,” Squadron said.

The existing plans call for 1,210 units of housing, a hotel and retail inside the so-called park to pay fees for the annual maintenance of the open space, instead of paying normal property taxes.

The inclusion in 2004 of private development ignited a controversy that has raged ever since and, in fact, may have carried Squadron into office.

He campaigned as a critic of the park’s plans in the fall election against longtime incumbent Marty Connor, who had supported the inclusion of housing in the public park.

This is the second bold proposition for Brooklyn Bridge Park in just over a week. Mayor Bloomberg said earlier that he is negotiating with Gov. Paterson for a city takeover of the lagging $350-million project as part of a swap that would also give the mayor control of Governors Island while putting the Javits Center entirely in the state’s hands.

Some sections of the park, including rolling lawns, a playground and a dog run, are slated to open by the year’s end and other elements are due by 2012, but roughly 33 percent of the park is on hold until additional public money is drummed up to pay for construction.

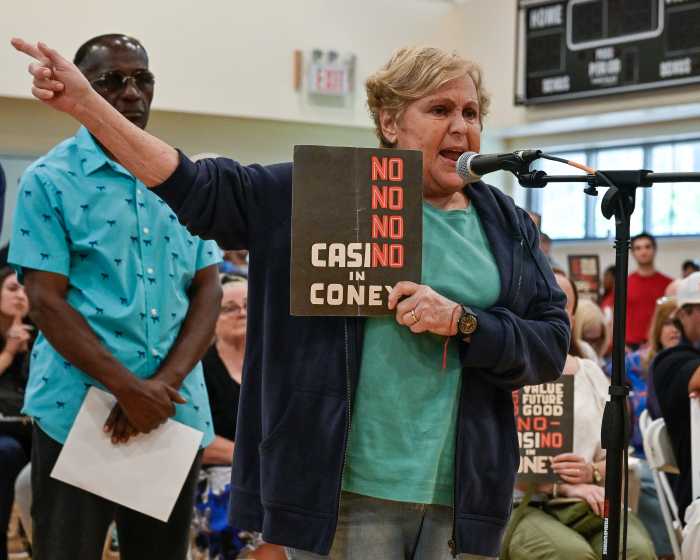

Squadron presented his scheme last Friday evening in Borough Hall to a room filled with dozens of the most outspoken critics of Brooklyn Bridge Park’s unusual funding scheme.

“This is brilliant,” said Sandy Balboza, head of the Atlantic Avenue Betterment Association, one of several people to congratulate Squadron’s idea.

But some eagle-eyed observers detected an Achilles Heel in the plan. Dan Wiley, a staffer for Rep. Nydia Velazquez (D–Gowanus) said the reliance on taxing increased land values might create an urge in City Hall to allow taller new construction near the park, while many neighborhoods have been trying to reduce permissible building heights.

And the Brooklyn Bridge Park Development Corporation opposes Squadron’s idea.

“With $4.3 million generated by the current residential properties for operations and maintenance and another $3 million to come on-line in 2010 and 2011, we are committed to the current development plan approved by the community, mayor and governor,” the development corporation said in a prepared statement.

The mayor’s office also had reservation about the tax plan.

“We would have concerns about a plan that relies on tax revenue from DUMBO to pay for the park, especially when you consider that new development will almost certainly include affordable housing the 421-a program,” said Andrew Brent, a mayoral spokesman, referring to a subsidy program that gives developers tax breaks if they include below market-rate housing in their buildings.

If DUMBO developers took advantage of the incentive, it would reduce the amount funneled towards the park’s upkeep.

But Councilman David Yassky (D–Brooklyn Heights) said in a statement that city officials should be more supportive of Squadron’s plan.

“[It’s an] innovative approach to funding the maintenance and operation of Brooklyn Bridge Park,” Yassky said in a statement. “The plan would provide a reliable and uncontroversial source of funding. The city should give the plan serious consideration.”