Just weeks after President Donald Trump blasted the plan on Twitter, federal authorities abruptly halted a $19 million feasibility study of a massive storm protection barrier off the coast of southern Brooklyn — prompting experts to advocate for smaller-scale, localized alternatives.

“We are in support of looking at innovations of resilience and applying them in places they are needed,” said Robert Freudenberg, the vice president of the Regional Plan Association.

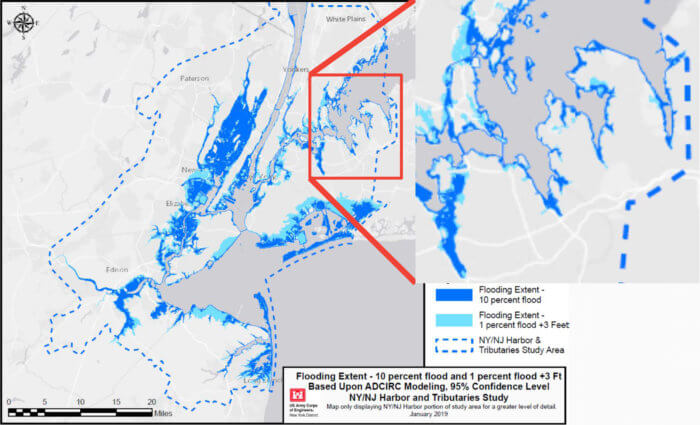

The US Army Corps of Engineers was halfway through its six-year, multi-million dollar storm resiliency study that examined four proposals to build storm-resilient infrastructure around New York and New Jersey.

The proposals included a $9 billion plan to build scattered levees and flood walls across the city’s coastal areas and a $62 billion sea wall equipped with retractable gates that would run six miles between the Rockaways and New Jersey.

However, the study came to a stop when the Army Corps announced on Feb. 10 that their 2020 work plan did not include funding for further research — less than a month after the commander in chief publicly called the potential sea wall “foolish.”

A massive 200 Billion Dollar Sea Wall, built around New York to protect it from rare storms, is a costly, foolish & environmentally unfriendly idea that, when needed, probably won’t work anyway. It will also look terrible. Sorry, you’ll just have to get your mops & buckets ready!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) January 18, 2020

Trump cannot unilaterally cut funding for the study, since the Army Corps’ funding is jointly decided by Corps officials, the Department of Defense, and the White House Office of Management and Budget — but the study’s sudden cancellation fueled speculation that Trump played an outsize role in the decision, the New York Times reported.

Many experts took issue with the president’s suggestion to use “mops and buckets” to clean up after storms, arguing that large-scale infrastructure is necessary to protect the low-lying coastlines — which according to the Army Corps, could be 10 feet underwater in 100 years.

“Mops and buckets did not cut it during Superstorm Sandy and will not work in Brooklyn or the Metropolitan area during another storm,” said Catherine McVay Hughes, a committee member of the New York-New Jersey Storm Surge Working Group. “We need an alternative for the economic engine of the country.”

Freudenberg also expressed his disappointment over the study’s cancelation, saying that the completed study alone would have created a treasure trove of valuable scientific research.

“To us, [the environmental impact report] alone is worth the value of the study,” he said. “To learn what these potential options that we have been debating for years in the region what the impacts could be and whether they are worth the costs that would be required.”

While many critics doubted the president’s reasons for weighing in on the study — saying he published the tweet for political gain — some environmentalist groups claimed the project’s cancellation presented a unique opportunity to rethink the entire storm-resilience push.

Kim Ong, a senior attorney at the Natural Resources Defense Council, said that massive sea walls presented destructive environmental consequences with only narrow benefits — since the sea-faring barriers fail to protect against rising sea levels and could potentially trap sewage.

“They have a very limited applicability,” she said.

Ong advocated instead for natural storm resiliency solutions, such as planting sea grass and bolstering sand dunes, as well as smaller levies that would be individually tailored for each location.

“They’re cheaper, they’re better for the environment, and they’re better for communities,” she said.

Others, however, claimed that natural remedies couldn’t protect against Superstorm Sandy-sized weather events, and said that the sea wall would prevent storm surges from flooding the drainage system and city streets.

“If the storm surge barrier were in place, during a major event its gates would be closed for a tidal cycle, thus cutting off the surge from the city’s shoreline,” Hughes said. “This will minimize the impact of the tidal surge inundating the drainage system, buildings and streets — and several hours later when the surge has passed and low tide has returned, the gates are opened.”