The artist selected by the city to design installations for Downtown Brooklyn’s Abolitionist Place started a three-month public engagement process for the project last week, seeking community input for the controversial project.

“The goal of the public programming is to hear from different communities about how they are making sense of abolitionist pasts, abolitionist presents, and abolitionist futures in order for me to generate the text to be engraved and featured on the free-standing structure,” the artist, Brooklyn-based Kameelah Janan Rasheed, wrote on her website.

The city’s Department of Cultural Affairs chose Rasheed in 2020 to create a public art piece commemorating the history of the Abolitionist movement and the Underground Railroad in the neighborhood. Last year, the Public Design Commission approved her conceptual designs for the project.

Local activists and historians have long been at odds with the city’s Economic Development Corporation ever since the agency announced plans to use eminent domain to demolish homes on Duffield Street, which has since in 2004, to make way for a park – what has since become Abolitionist Place. In 2008, the city announced that they would be providing $2 million for “In Pursuit of Freedom,” which included funding for an art installation commemorating local anti-slavery activity, at the park. Last year, neighbors spoke out against the Rasheed’s proposal, saying it did not adequately represent local abolitionist history, and the EDC for a lack of transparency as they commissioned the piece.

“I want to jump immediately into an overview of the concerns that have been expressed about the public art portion of this project, in particular what I have sort of offered as a proposal,” Rasheed said at a virtual introduction session on Jan. 24. “I think it’s always good to start at a place of, I love this. This is really exciting for me, and I’m really excited to be a part of this process, and to hear from people about the things that they’re feeling about the project and about my contribution.”

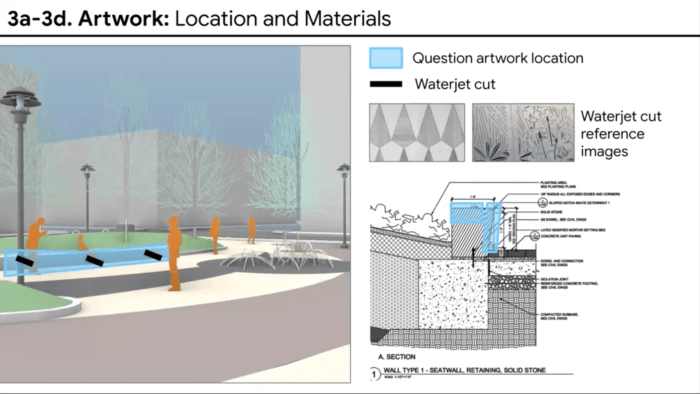

In her approved proposal, Rasheed said her work, titled “Questions Worth Having Answers To,” would feature engraved text acknowledging the future of abolition on the ground and on benches around the park, and install a freestanding statue. Neighbors and activists immediately criticized the work for not acknowledging local anti-slavery activists, including Harriet and Thomas Truesdell, who lived at 227 Duffield St., directly beside the future park, or sisters Sarah Smith Garnet and Dr. Susan Smith McKenney.

Rasheed noted that she had also been accused of being a “puppet” of the EDC, and that some locals had said that the public engagement process was “fake,” and that the feedback she received would be ignored.

“What I’m hoping to do tonight is not to petition for your like of me or for the project, but just to actually inform folks a bit more about what the project is designed around and ideas that are important, as well as the community engagement process,” she said.

For now, that engagement process includes a second introductory session on Feb. 7 and two meetings of an “Abolition Study Group,” though the first meeting of the study group, on Jan. 30, was cancelled just before the event was set to start. Rasheed will also be connecting directly with local organizations and residents, and invites them to send their thoughts or schedule a phone call on her website.

Community members didn’t hold back at the first introductory session, firing off questions about Rasheed’s knowledge of the neighborhood and the EDC’s history of demolishing historically-significant homes on Duffield Street.

Last year, the city landmarked and purchased 227 Duffield St., the final house remaining on the block, scrapping a developer’s plans to demolish the home and ending a years-long struggle between city officials, local activists, and the residents of the houses.

Perhaps the best-known of those residents was Joy Chatel, also known as “Mama Joy,” who owned 227 Duffield St. and successfully fought to keep the building standing as the city sought to seize it to develop what was then called Willoughby Square Park. The house and its now-leveled neighbors had been part of the Underground Railroad.

“I think it’s important that while the house is saved, it’s also important to realize the activity of the whole general area, and I think that’s what the park symbolizes,” said Suzanne Spellen, a local writer and architectural historian.

Large parts of Downtown Brooklyn used to be residential and were home to the borough’s African American population, and to the abolitionist movement. But most of the physical structures — houses, churches, and more — are gone now, Spellen said. She leads a walking tour of African American history that starts in Brooklyn Heights and ends at 227 Duffield, but there are only three buildings still remaining to see. Often, she’s explaining the long-lost history of what’s now a parking lot or industrial site.

Spellen hasn’t been as deeply involved with the development of Abolitionist Place as some of her colleagues are, but said she hopes the final installation is educational and a little “in your face.”

“I think you have to do something that is a little more visual, a little more interactive in some way, that you can’t just walk past it and not know that something happened there,” she said. “Even if you don’t have time to really look at what it was. They need to put something in place that really intrigues even the person in a hurry.”

Local historian Raul Rothblatt was frustrated by the format of the first introductory session. Rasheed spoke and shared her screen via Zoom while attendees sent their questions via the application’s Q&A feature, and he found it difficult to concisely formulate his concerns that way.

Still, he called the session an “improvement” over the EDC and the PDC’s past sessions, where he felt the public hadn’t been able to register their concerns at all.

He feels the proposed monument breaks the city’s commitment to erect something that commemorates the 19th century abolitionist movement, and wants the design process to feel like a more genuine conversation between the city, Rasheed, and the community.

“We have so much support for Sisters in Freedom, our monument,” he said. “That means a representational piece of art about these specific women.”

That monument, brainstormed by the community and supported by an array of local elected officials and nearly 5,000 locals who have signed an online petition, would depict a selection of the women who were pivotal to the local abolitionist movement, including journalist Ida B. Wells, who found safety on nearby Gold Street after fleeing her home in Memphis.

Rothblatt said his frustrations are not with Rasheed herself, and that he and his colleagues support her and her art. Most of his ire is directed at the PDC and the EDC, who were behind the successful push to buy and demolish the historic homes on Duffield Street.

“It was the EDC that really chose the one that was furthest away from the city’s commitment,” he said. “They should have been especially mindful given that this land was confiscated through eminent domain.”

Earlier this month, activist and historian Jacob Morris filed suit against the PDC, claiming that the agency had acted against its own rules in approving the conceptual design last year.

“They’re not going to get rid of us, they’re going to have to live with us for forever,” Rothblatt said. “We will continue to tell the story. My goal is to reframe Downtown Brooklyn, this should be New York City’s primary destination as a representation of freedom.”

Correction 1/31/2022: An earlier version of this story said the Economic Development Committee had chosen Rasheed — the selection was made by the city’s Department of Cultural Affairs.