They’d rather take the stairs.

The Metropolitan Transportation Authority must make major changes to its plan to add an elevator to Sunset Park’s 59th Street station on Fourth Avenue, because the construction will create a traffic nightmare on the avenue, said members of Community Board 7’s transportation committee at a July 19 meeting with reps from the authority. The board’s district manager said that the current plan would cause major disruption and even dangers to the community because it ignores existing traffic and parking problems, among other factors.

“You’re planning in a vacuum,” Jeremy Laufer told authority reps.

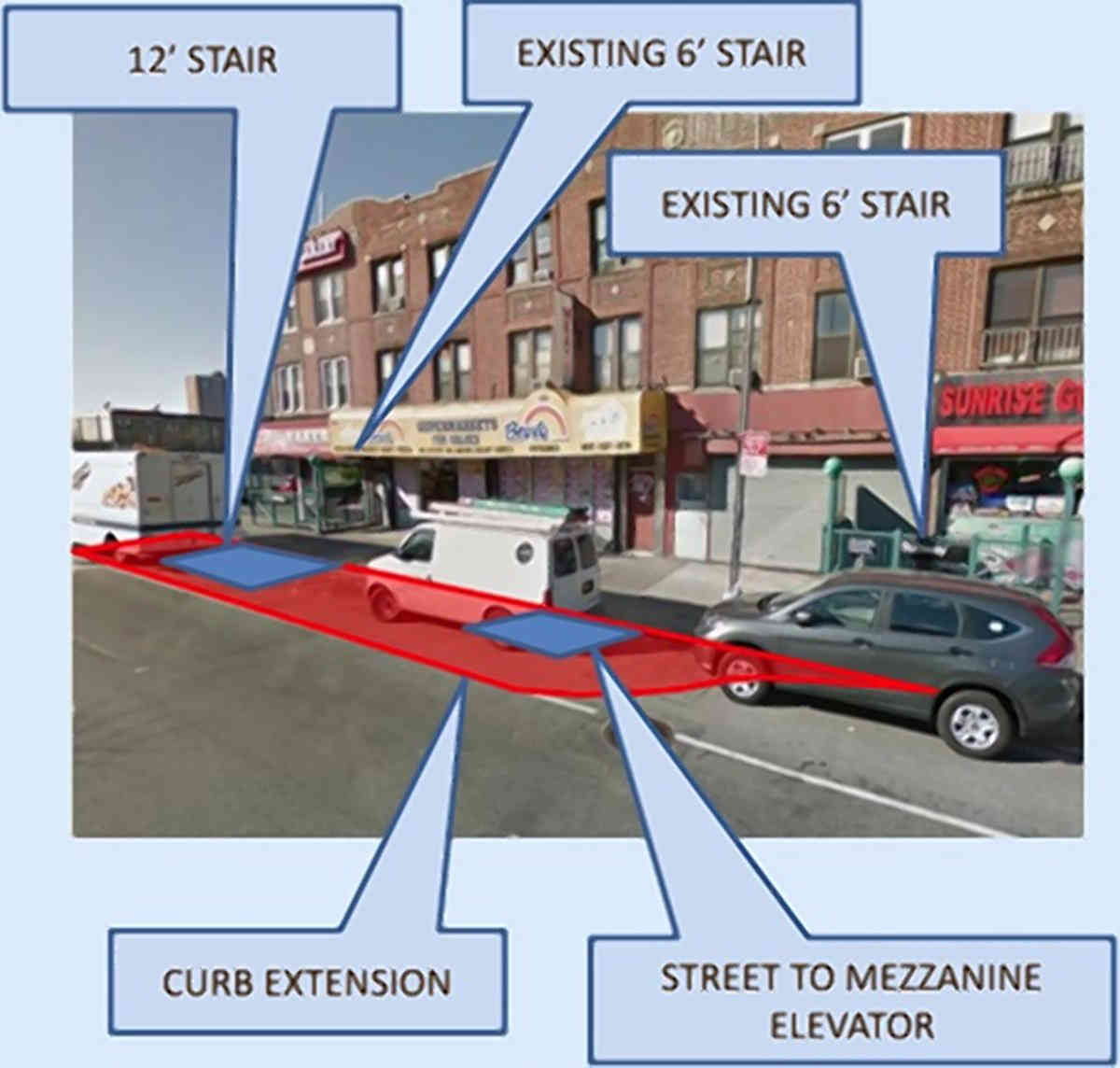

The construction will include the installation of one elevator on the west side of the street, closer to Third Avenue, between 58th and 59th streets, and two elevators underground, to transport riders from the mezzanine level to both the Coney Island and Manhattan-bound platforms. The transportation authority will also build a new staircase from the street to the mezzanine, move the current mezzanine-to-platform stairs to accommodate the new elevator, and expand the mezzanine.

The transportation authority plans to start construction on the project early next year — a year later than originally planned — and the full project will take nearly three years to complete, according to the authority’s assistant director of government and community relations, Andrew Inglesby, who attended the meeting with the project’s design manager, Bhargav Shah.

But the first nine months of the project will make driving — and finding parking — particularly difficult for locals, the transit reps admitted. Construction of the two new underground elevator shafts will require workers to excavate the street and close the two lanes on each side of Fourth Avenue — on the blocks between 57th and 59th streets, and on part of the block between 59th and 60th streets — and convert the parking lanes into driving lanes.

“We’re not going to lie to you — this is going to be a project where we’re going to have a very strong, long street impact,” Inglesby told board members. “The bottleneck will be nine months.”

The sidewalk extension to accommodate the street elevator will permanently eliminate four parking spots, but neither the authority reps nor Laufer knew how many total parking spots the project would temporarily eliminate on the three blocks.

Laufer complained that converting the parking lanes into driving lanes would be dangerous for pedestrians on the sidewalks — and particularly for the kids walking to PS 503 on 59th Street between Third and Fourth avenues — unless the authority also installed barriers between the parking-turned-driving lanes and the sidewalk. A rep from the Department of Transportation promised that the agency would make including the barriers a stipulation in the construction contract.

Another board member pointed out that the temporary elimination of three blocks worth of parking spaces would make the whole neighborhood’s already bad parking problem even worse.

“Because of the elimination of parking, it’s going to put stress on the other blocks,” said Tom Murphy.

Murphy and Laufer also said that the transportation department would need to add signage in the area to mitigate traffic problems — both on Fourth Avenue, to divert drivers to Third Avenue, as well as on the Belt Parkway, warning drivers of the construction off the Fourth Avenue exit.

And Laufer asked how the authority would ensure that construction would finish up on schedule — and especially before next year’s New York City Marathon in early November, which runs up Fourth Avenue. Inglesby vowed that the authority would make sure the contractor cleaned up the area before the marathon — even if the work wasn’t finished by the time of the race.

Shah, the design manager, also said that the authority’s contract offers the contractor a monetary incentive to finish the nine months of work a month ahead of time.

But when he added that the MTA would collect a penalty from the contractor if the work took more than nine months, Laufer demanded to know why the money wouldn’t go directly to the community that’s impacted by drawn out construction.

“How does that improve things for the community, if we’re the folks affected?” Laufer asked. “How about we put that money back into the community rather than MTA taking [it]?”

The district manager also said that letting the authority pocket the penalty makes it seem like a slower project would actually benefit the authority.

“It seems to me that that incentivizes the MTA to have a slower project.”

But Inglesby said that assumption was false, and that the authority did not want the community to suffer for longer than it had to.

“I can honestly say, that is not the case,” he said.