Some of the greatest works of modern art have been derided by the simplistic put-down, “My kid could do that.”

So it’s refreshing to finally attend an art opening where no one’s kid could have done anything of the kind.

I’m talking, of course, about the hottest art exhibit in town, the Museum of Drunken Art, which is now gracing the walls of Freddy’s Bar in Prospect Heights.

There’s Peter Teraberry’s “Bottle Head,” a paean to the drunken life of a young, stressed out urbanite.

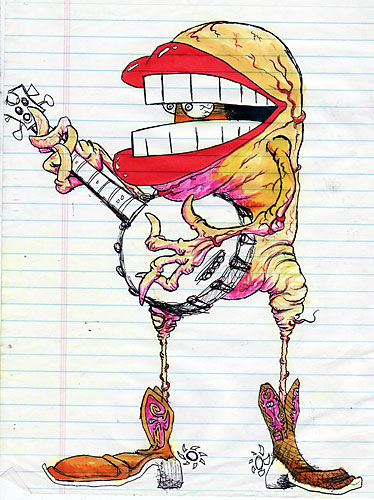

And there’s Sam Crees’s “Psycho-billy” (at right), which appears to be a cowboy-booted, banjo-playing testicle with stage fright.

And let us not forget Tim Harrod’s “Filbert the Furry Friend,” who smiles and brays, “Hiya, kids! I wanna f— your mom!” (pen on napkin).

No, my friends, you kids could not have done any of this (unless, of course, your kids are into your liquor cabinet, in which case someone should call ACS, not MOMA).

And that’s because great drunken art often has an element of crassness, said Teraberry, who is not just a legend in the drunken art world, but also the “museum’s” “curator.”

“The best drunken artists often return repeatedly to the uncouth and the unrefined,” he said. “There’s often depictions of alienation” — though, he admitted, the inspiration is usually three parts Johnny Walker to one part Dear John letter.

It’s undeniable that the history of modern art and the history of drunken art are forever linked. Jackson Pollock, Francis Bacon, Picasso and, um, that other guy I can’t remember right now were drunk a lot of the time — and they did pretty good for themselves.

Oh, yeah, and that Van Gogh guy. He was messed up a lot!

To better appreciate the fine works hanging on Freddy’s walls, I got pretty damn drunk the other night and pulled out a pen and my reporter’s notebook. Through the foggy haze of a pint of Blue Point Toasted Lager (I wasn’t so drunk that I forgot that they don’t sell Brooklyn Lager at this anti-Atlantic Yards bar), I remembered Teraberry’s words — “Drunken art often goes to the dark place of one’s soul” — and went to the darkest place I know: home plate when I was a kid in Little League (pictured).

Staring back at the abject horror of the memory of that fatal strikeout, I switched to Jameson in hopes of broadening my artistic palate.

But I was still in my own heart of darkness, churning out a reasonable Dick Cheney, rifle in one hand and an upraised finger in the other, cursing out a smiling Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad (front page). You don’t need to drink a fifth of tequila to see that I got Cheney’s crooked snarl almost perfectly!

But still, I was unsatisfied. Finishing off the bottle, I crafted what I consider my darkest, deepest masterpiece (right): an angry scrawl depicting the rubber-band-dropping mailman who has made my block a living hell of stretchy litter (you don’t need an art historian to make sense of that; just read my four-part, soon-to-be-award-wining series on this devil mailman by clicking here: www.brooklynpaper.com/search/?q=rubber-bands”>http://www.brooklynpaper.com/search/?q=rubber-bands).

Clearly, my work is ready to hang on the walls of Teraberry’s sacred gallery. But had I learned anything? Teraberry suggested that I was asking the wrong question (damn his sophistry!).

“The question is: did you have fun?” he asked. “A lot of people have forgotten that art can be fun. It’s like when you’re in school and you doodle when the teacher is talking. That’s the most fun you have with your art. But then when you grow up and study art, you’re told that such mockery, such juvenile spirit, is somehow invalid. They turn art into something pretentious and pseudo-religious.”

The great drunken artist had achieved that moment of clarity, that perfect balance between self-consciousness and unconsciousness that is so elusive. Yet he said he was sober. Too bad.

So we draw on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.

I didn’t write that; F. Scott Fitzgerald did. He was a drunk, you know.

Museum of Drunken Art at Freddy’s Bar (485 Dean St., at Sixth Avenue, in Prospect Heights), through Nov. 30, free. Call (718) 622-7035 for info.