Who’s going to bail out the bail bondsmen?!

The Brooklyn bail industry is reeling from recently enacted state-wide bail reforms, with the owner of one decades-old Downtown firm preparing to shutter multiple storefronts in response to a rapidly shrinking market.

“We’re not going to able to sustain rents and payroll if there’s no bail,” said Wendy Fordin-Saler, one of the owners of Empire Bail Bonds on Livingston Street. “It’s emotionally and mentally traumatizing to say the least.”

The family-owned business, which has operated its office in America’s Downtown for a quarter of a century, closed shops in Queens, Long Island, and Westchester at the beginning of the year as a direct response to defendants of low-level criminal charges — who make up 95 percent of their clientele — no longer having to make bail, according to Fordin-Saler.

“We’ve had to lay off dozens of employees, we’ve already closed three of our six locations and if this continues on, we’re going to lay off a lot more staff and close all our brick-and-mortar locations,” she said.

State legislators and Governor Andrew Cuomo passed laws in April which took effect on Jan. 1, limiting judges’ ability to impose bail on most misdemeanors and non-violent felonies, while not allowing them to keep defendants in custody pre-trial for any misdemeanors and most non-violent felonies.

Fordin-Saler and her competitors in the bail industry strongly oppose the reforms, including one prominent Brooklyn bondsman, who complained that some patrons — whose bail was retroactively eliminated as a result of the new laws — have already cut ties.

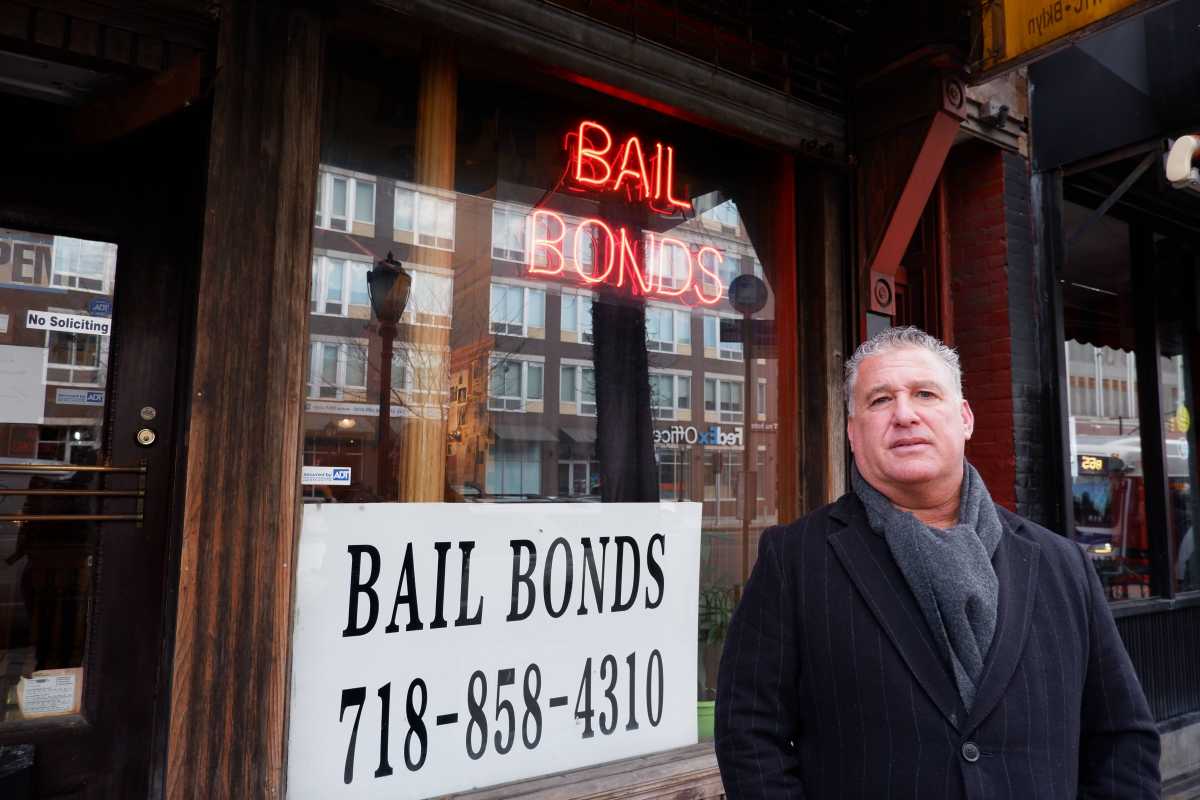

“I have clients coming into my office saying ‘I don’t have to check in with you anymore,’ and laughing,” said Ira Judelson, who has arranged large bonds for disgraced movie mogul Harvey Weinstein, mixed martial arts fighter Conor McGregor, and the former director of the International Monetary Fund Dominique Strauss-Kahn. “It’s going to cost taxpayers when you realize all the money going into bring people back.”

Judelson — whose Atlantic Avenue office lies directly across from the recently-shuttered House of Detention — often deals with clients who have to post large amounts of bail for felony charges, and roughly half of his customers fall outside of the new laws.

Advocates pushing for reforms argued that the state’s former bail system resulted in the mass incarceration of poor New Yorkers who had not been convicted of any crimes, while their well-heeled counterparts could afford to buy their way out of jail.

To illustrate the disparity, Public Advocate and former Canarsie Councilman Jumaane Williams compared the case of Weinstein — a millionaire film executive accused of sexually assaulting two New York women — to the tragic circumstances surrounding the 2015 suicide of Kalief Browder, who spent three years on Rikers Island awaiting trial, because he couldn’t affording $3,000 bail on charges related to the theft of a backpack.

“I can think of no clearer example of why these reforms were so critical than the fact that just a block behind us Harvey Weinstein arrived for his trial today under his own power, while … Kalief [Browder] couldn’t afford to go home,” Williams said in Manhattan Tuesday.

The Brooklyn bail industry in particular has suffered under policy’s enacted by District Attorney Eric Gonzalez prior to the state-wide bail reform. The Kings County prosecutor — who effectively decriminalized possession of small amounts of marijuana in the borough — requested bail in only seven percent of misdemeanor cases in 2019, and several of Judelson’s competitors in and around Downtown Brooklyn had already closed shop in the years leading up the new laws taking effect.

On the other hand, the closure of the Brooklyn House of Detention as part of Mayor Bill de Blasio’s borough-based jails plan has not deeply impacted either bail bonds company, according to Judelson, who said that most of their business comes from the nearby criminal and supreme courts in Downtown Brooklyn.

But the state’s trend toward enacting progressive criminal justice reforms may reduce the state’s bail bonds industry of slightly more than 200 licensed agents by half, according to the head of the trade organization the New York State Bondsman Association Michelle Esquenazi, who said most bail-bonds businesses are not large enough to weather a longterm recession.

“They’re family-owned business, they’re not multimillion dollar enterprises,” said Esquenazi, who also owns Empire Bail Bonds. “It will affect everyone at a 50-percent ratio.”