Rock and roll stands at the intersection of spontaneity and artifice.

For every guitar-smashing, audience-diving moment of freedom in a classic American rock show, there’s at least a dozen scripted moments cooked up in a record company’s PR office designed to generate buzz for the talent or get a song on the radio.

That’s the essential dilemma behind the Brooklyn Museum’s massive new fall show, “Who Shot Rock & Roll,” a sprawling and captivating look at the last 60 years of American popular music as seen through the lens — or, more accurately, the lenses — of some of the world’s greatest photographers.

A viewer can’t help but have trepidations about a show that purports to take fans “behind the scenes” with “portraits that go beyond the surface and celebrity of the musicians.” After all, an earlier Brooklyn Museum retrospective of Annie Leibovitz’s celebrity photos did just the opposite — strengthening rather than debunking the notion that celebrities can never truly be real people and that nothing is unscripted, even a seemingly spontaneous photograph.

And there are whole sections of “Who Shot Rock & Roll” that fall victim to that curse of our age and recall the co-conspiratorial role that the media has played in creating, packaging and marketing celebrities.

As a result, many of the images on display here — striking, compelling, amazing images of some of the most famous people in modern history — are actually sad, such as album art of Lil Kim by David LaChapelle, Andy Earl’s famous Bow Wow Wow cover or virtually any photo of David Bowie, because of how little spontaneity some musicians are able to muster.

Bob Dylan, it is noted in the accompanying text, refused to allow the public to see any unapproved image of him, lest they create their own counter-image to the one he was crafting.

An entire section devoted to portraits of famous rockers is especially disappointing for this reason. But that’s the nature of portraiture — from the Gilbert Stuart painting of George Washington that hangs just outside the exhibit to the photo of Eminem holding a lighted firecracker where his penis should be.

It’s the same myth-making, only this time on celluloid, not canvas.

Fortunately, the exhibition does not wallow too long in Annie Leibovitz’s celebrity-obsessed stop bath.

In fact, the bulk of the show is devoted to an attempt to explain what makes rock and roll so vital to our culture. It opens with a few great shots of Elvis Presley — and in one photo from 1956, the singer strokes the hair of a fan while another girl looks on, her mouth just beginning to contort into the shape it might take if she had seen Jesus himself.

And this was before Elvis was even the King!

Other shots in this sequence — one of the Rolling Stones looking more like art school geeks than Angry Young Men, for example — remind us all what our greatest living musicians were like before the drugs, the tours, the breakups and all the marketing turned them into products on the shelves or downloads in the iTunes store.

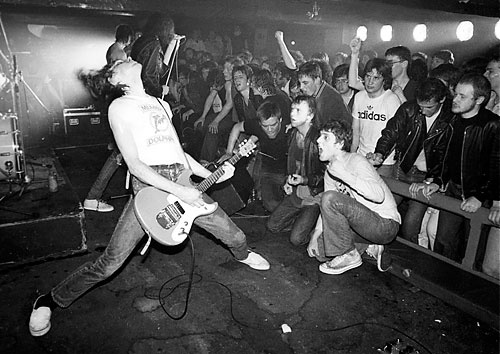

An entire section devoted to “performance” helps capture the essence of a rock and roll show through iconic photos of Jimi Hendrix burning his guitar, Johnny Cash flashing his middle finger, Iggy Pop sweating through his jock strap, the Ramones surrounded by teenage boys on stage at CBGB, Tina Turner contorting, Ike Turner glaring at her, Janis Joplin spilling out of her dress, and Paul Simonon smashing his ax during a Clash show.

And lest we forget, every photo in the exhibition is a classic — a classic of composition, of printing, of technique. Some are real moments in time, like Ian Tilton’s shot of Kurt Cobain crying — really crying, not just fake crying — after a show. Others are artificial moments — like Albert Watson’s perfectly composed, in-camera, double-exposure of the faces of Mick Jagger and a leopard — that nonetheless remind us how good good photography can be.

Of course, it gets even better when given a context. Indeed, that famous photo of John Lennon in that New York City T-shirt has been seen so many times that it — and the man at the center — have become banal. It’s on display here — but curator Gail Buckland doesn’t just give you that photo, but Bob Gruen’s entire contact sheet so you can see Lennon in a larger, illuminating context. If you’ve viewed that photo a thousand times, it’s refreshing to see that just seconds earlier, Lennon was making silly faces, not posing as an icon.

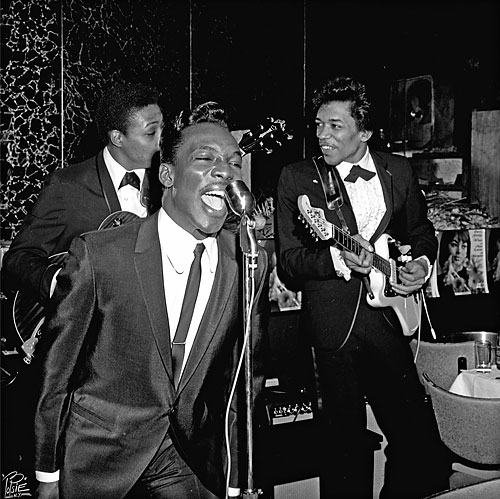

And it’s also great to see that two years before he was a rock god, Jimi Hendrix was just a smiling backup guitarist in Wilson Pickett’s band.

No, “Who Shot Rock & Roll” does not answer the existential question of whether there was ever a truly unscripted moment in the history of America’s seminal pop culture movement, but by the end of its 180-photograph ride, at least you know that movement’s power.

“Who Shot Rock & Roll” at the Brooklyn Museum [200 Eastern Pkwy. at Washington Avenue in Crown Heights, (718) 638-5000], Oct. 30-Jan. 31, 2010.