“The Nutcracker” is a classic for a reason. The show is a holiday tradition at ballet companies around the world, and has served as inspiration for a great many ballerinas who saw it as children and realized they wanted to dance in it someday.

It’s also quite old. The original “The Nutcracker” debuted in Saint Petersburg, Russia, in 1892, and is actually an adaptation of an 1819 short story by E.T.A. Hoffman. Perhaps the most famous version of the ballet, by George Balanchine, debuted at Lincoln Center in 1954, and has been performed there every year since.

In Brooklyn, though, “The Nutcracker” is ever-evolving. Two different versions are opening Dec. 12: the Brooklyn Ballet’s “The Brooklyn Nutcracker” and the Mark Morris Dance Group’s “The Hard Nut.”

A week before opening, Brooklyn Ballet’s founder and artistic director Lynn Parkerson watched closely as dancers practiced to Pyotr Tchaikovsky’s classic, lilting orchestrations.

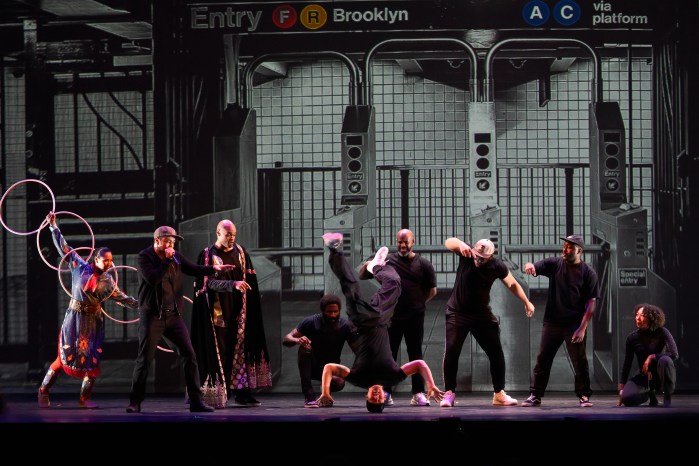

“The Brooklyn Nutcracker” retains many of the hallmarks of Balanchine’s ballet — the music, much of the dancing, the iconic snowy close to Act I. But it’s set in modern Brooklyn and is woven through with local culture and traditions.

The show debuted in 2016, but started to come together in 2010, when Brooklyn Ballet choreographed the mechanical doll dance with a ballerina and a hip-hop dancer and performed it on the street. That dance is still part of the ballet today.

Seeing Brooklyn at the ballet

“The community just went nuts for this kind of interaction between this community and the classical form,” Parkerson said. “We added more and more dances, more and more scenes, more costumes. It just kept growing and growing.”

At the Brooklyn Ballet, the story is centered not around the Nutcracker and Clara, but around Herr Drosselmeyer, who brings the Nutcracker to the Christmas party at the start of the ballet.

“It’s really about [Drosselmeyer] and his family and him being in the center of things,” Parkerson said. “It’s less about the brother breaking the nutcracker, and more about his dream, of old Brooklyn and then this new space that he’s wandering around in that is now.”

Drosselmeyer isn’t a ballet dancer, but a pop-and-lock hip-hop dancer. In the classic battle scene, young dancers marching with prop rifles have been replaced by a fight between ballet and hip-hop dancers.

For a long time, “The Brooklyn Nutcracker” didn’t feature the ferocious Rat King, the main antagonist of the Balanchine ballet. Then, a few years ago, the company welcomed a dancer who seemed destined to bring the character to life.

“We got to know a certain kind of dancer, a street dancer with this krumping style, and he had done the Rat King in a past life or something,” Parkerson said. “I immediately thought, we have to add that.”

Artist Avram Finkelstein, a Brooklyn native who used to create art for the AIDS activist group ACT UP, created the sets alongside the Brooklyn Ballet team, Parkerson said. His projections bring the show to the Brooklyn Botanic Garden, the subway, and provide magical backdrops to famous dance sequences like “The Waltz of the Flowers.”

“He’s just a phenomenal artist, and he’s from Brooklyn, he grew up in Brooklyn, and he knows the landmarks,” Parkerson said. “He’s the art director and did all the projections … kind of enhancing each scene, so you sort of travel from space to space.”

Crossing through cultures

One of the most significant changes to “The Brooklyn Nutcracker” comes in Act II, as the Sugar Plum Fairy introduces sweets from around the world. In other productions, the procession includes “Arabian Coffee” and “Chinese Tea,” often with racially and culturally insensitive costumes and imitative dances. In recent years, many companies have re-imagined the sequence.

In “The Brooklyn Nutcracker,” that scene has always been different.

“We have Chinese dancers doing a classical Chinese dance, and we have a Middle Eastern belly dancer instead of a ballet dancer imitating the form,” Parkerson said. “The classical Chinese dance is so beautiful that it made complete sense to bring that to the production, particularly when you live in a community when you have all these dancers and all these folks from all over the world.”

Each dance is accompanied, as of last year, by a live musician — a Palestinian violinist, a Chinese flute player, African drummers. Elsewhere in the show, a beat-boxer accompanies the hip-hop dancers, and an accordion plays alongside a traditional Ukrainian folk dance.

“We’re crossing different time periods and through the cultures of different people,” Parkerson said. “Each of the [sequences] has a traditional instrument that’s connected to that dance.”

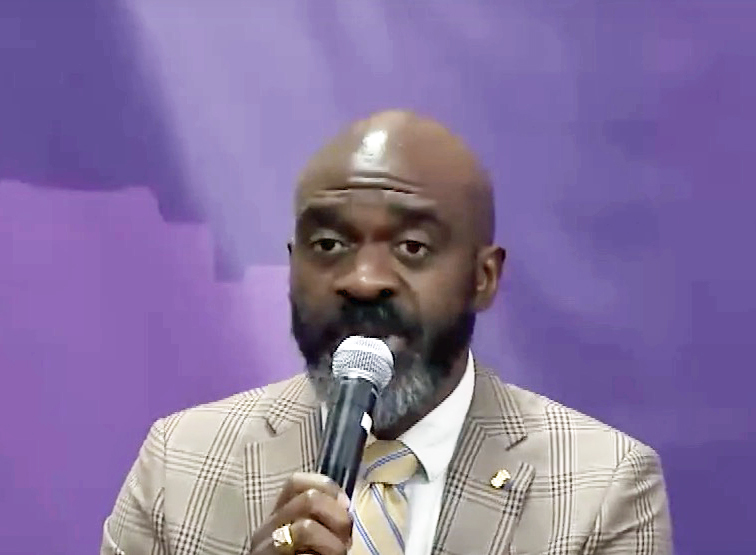

Tristan Grannum, the Brooklyn Ballet’s director of community engagement, is also a rehearsal director and a dancer in “The Brooklyn Nutcracker,” where he performs one of the ballet’s most iconic sequences – the Snow Pas de Deux, a tender dance between the Snow King and Snow Queen.

It’s his favorite part of the show, as a dancer. The Snow Pas typically has the King and Queen dressed in big, elaborate, frosty costumes. In “The Brooklyn Nutcracker,” the King wears a button up and dress pants, Grannum said, and the Queen a long, flowing dress. Now in his third year in the role, Grannum said he’s gotten more comfortable with the dance and better at expressing the love between the two characters.

“For me, it really, really shows this love story,” he said. “I think through the viewer, you can create multiple stories from this. I get emotional even dancing it.”

Diversity in the theater

Grannum grew up in Flatbush, and has performed in ballet companies around the country. He said “The Brooklyn Nutcracker” is “the most diverse, the most innovative Nutcracker I’ve ever been in.”

It’s an ode to Brooklyn, he said, something any longtime resident will recognize and appreciate, and the show has given a platform to street dancers not usually recognized on stage.

“Typically, you see them dancing in very underground work, or in the train station, outside, doing it more for fun,” he said. “But to see them in a professional setting … you’re seeing moreso the value of their dance style, it’s just as important as ballet.”

There’s also value in the different body types, aesthetics, and styles of the dancers at the Brooklyn Ballet, he said, and the fact that Brooklynites might spot their own neighbors among the company.

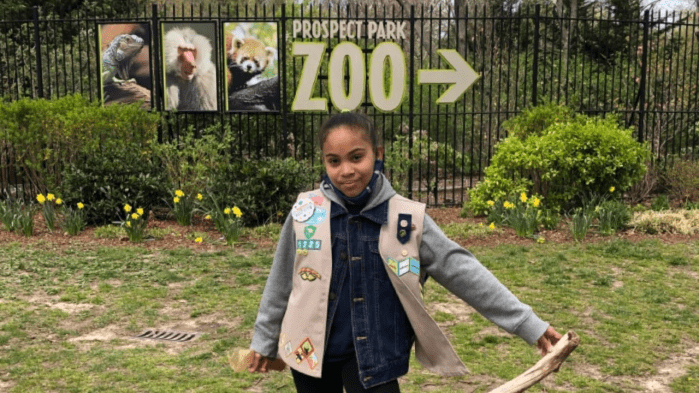

Grunnam also loves introducing young Brooklynites to “The Nutcracker” and to the world of ballet, and his job there is twofold — he dances, of course, and organizes $10 community matinee performances of “The Brooklyn Nutcracker.”

Often, the students who attend those performances have never seen a professional ballet before, he said, and when they meet Grunnam and his colleagues at the Brooklyn Ballet, they realize for the first time that they could be dancers, too.

“Most of the time, people’s connection to ballet and to dance is through ‘Nutcracker,’” Grannum said. “You hear across the board from ballet dancers, ‘I became a ballet dancer because I went to see ‘The Nutcracker,’ so to know we’re able to give four to 5,000 students access to see this performance, that’s 4-5,000 potential pathways to becoming a ballet dancer … which is then also going to be diversifying the entire art form.”

While his time dancing at the Brooklyn Ballet is coming to an end relatively soon, Grannum intends to stay around in his other roles. While other companies started to prioritize diversity and cultural inclusivity after the pandemic — especially after the Black Lives Matter movement of 2020 — those values have always been central at the Brooklyn Ballet.

“I think more people need just need to understand that Brooklyn Ballet has been doing the work before everyone else,” he said. “Brooklyn Ballet was doing that … since its inception 23 years ago. I want people to understand that our message has been throughout our history.”

“The Brooklyn Nutcracker” opens on Dec. 12, with performances through Dec. 15, at The Theater at City Tech, 275 Jay St. between Tillary Street and Tech Place. Tickets start at $35.