The city this spring will break ground on renovations to a long-shuttered World War II memorial Downtown — one year later than initially planned, due to an accounting error that left officials scrambling to come up with enough cash to complete the project.

In March 2017, news broke that the Department of Parks and Recreation collected the $4 million it needed to make the shrine inside Cadman Plaza Park handicap accessible, and that the memorial — which is normally open to the public for special programming and events — would be brought up to code within 18 months.

But that pot of money — a mix of taxpayer dollars allocated by Borough President Adams and Downtown Councilman Stephen Levin, and payments that the United States General Services Administration made to the Parks Department in order to use other city land as a temporary parking lot — turned out to be $1-million short, according to a Parks spokeswoman, who said the agency expected to receive some $2 million in payments from the Feds, but only got half that.

“Our records indicated that there was approximately $2 million available from the United States General Services Administration, but upon looking into it further we discovered there was only about $1 million,” the spokeswoman said.

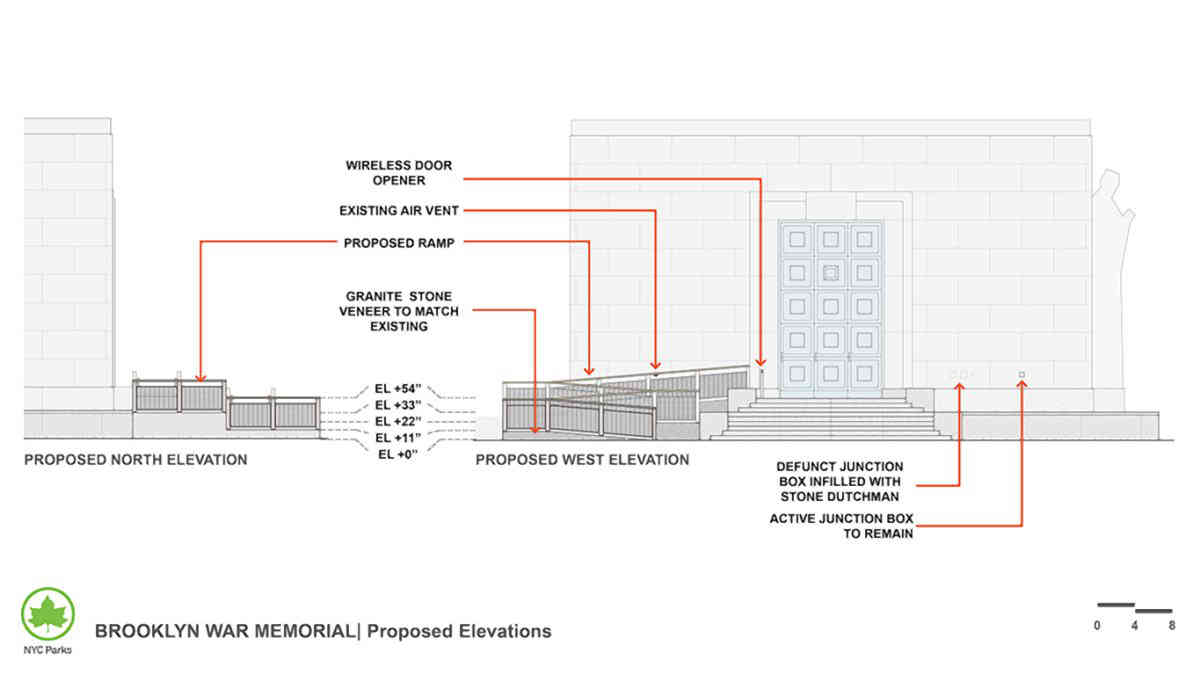

Agency leaders then tapped the beep and Mayor DeBlasio for the extra green they needed to make the memorial accessible to all by installing ramps and an elevator from the ground floor to its basement bathrooms, according to the rep.

And now, Parks Department leaders claim they have all the money they need to make over the shrine, whose interior features the names of more than 11,500 Brooklynites who died in WWII, and will still only be open to the public for special events or by appointment following the renovations.

“The most important thing here is that the project is fully funded, on track, and moving forward,” the agency spokeswoman said.

But some veterans who served in the war and lived to tell about it fear they may never get to see the spruced up memorial, and the names of their fallen friends within it, due to the years of delays.

“Before we kick the bucket, my brother and I want this thing to get done so people can go visit,” said Marine Parker Jack Vanasco, 91, a WWII vet who fought alongside his now 93-year-old brother, Roy Vanasco. “A lot of guys we grew up with, played ball together with, are on that wall — at least a dozen or so.”