The proposed Coney Island casino would likely clog local roads with heavy traffic and overwhelm public parking, according to documents submitted to the state.

An Environmental Impact Statement included with The Coney’s casino license application shows that the casino, if approved, is expected to bring thousands of cars to the neighborhood every day — more than can be sustained comfortably by existing roads, highways and parking spots.

The Coney — backed by a team of companies including local developer Thor Equities — is one of eight prospects vying for three new Downstate casino licenses. Applicants submitted their materials to the Gaming Facility Location Board in June, and the licenses are expected to be granted by the end of the year.

First, though, each proposal is being reviewed by a six-member Community Advisory Committee.

The Coney — which would include a hotel, retail stores, a convention center, and more across 1.6 million square feet — would draw about 8 million visitors per year, per the application, or 20,000 per day, and employ about 4,500 people.

As of 2017, the whole of Coney Island saw about 5 million tourists annually — meaning the casino bring the nabe’s number of annual visitors up to 13 million, on top of the roughly 120,000 people who reside there permanently.

More people, more traffic

On weekdays, the 24/7 facility would generate more than 5,000 vehicle, truck, and taxi trips, according to the EIS. But while the document provides trip data for weekday mornings, afternoons, evenings, and nights; it only offers data for Saturday afternoons and nights.

About 3,203 vehicle trips would be generated during those hours on Saturdays; compared to 3,199 generated during the same hours on weekdays.

Roughly 20% of all casino-related trips would involve the subway, per the EIS, or roughly 4,000 trips based on the estimated 20,000 daily visitors.

The extra trips would cause significant congestion on parts of the Belt Parkway and its exits, the report states.

The westbound off-ramp between Coney Island Avenue and East 7th Street, for example, currently sees about 3,934 vehicles per hour on weekdays between 5:15 and 6:15 p.m. and operates at what the Highway Capacity Manual classifies as “Level of Service C,” meaning traffic flows relatively freely.

If the casino were built, the exit would see 4,589 vehicles per hour on weekdays, per the EIS, and would be moving at Level of Service F — stop-and-go traffic. Between East 6th and 7th streets, the westbound Belt Parkway would be similarly snarled on weekday evenings; while Saturdays would bring significant delays to the belt east of Coney Island avenue and between East 6th and West streets.

Dozens of local intersections would be similarly clogged at various points in the day, particularly on weekday evenings and Saturdays. The intersection of Surf and Stillwell avenues, near the casino’s entrance, would operate at LOS F on weekday evenings, and drivers could be held up at the traffic light for upwards of six minutes. A portion of Stillwell Avenue south of Surf Avenue, near the boardwalk, would be closed to vehicles and made pedestrian-only.

The EIS predicts similar delays at the intersection of West 12th Street and Surf Avenue and several blocks away, where Cropsey Avenue and West 17th Street meet Neptune Avenue.

In an effort to relieve congestion, the casino plans to re-stripe the road to create new lane patterns at the intersections of West 12th Street and Surf Avenue and West 15th Street and Surf Avenue; add an all-way stop at West 15th and Bowery streets, and install a new three-phase traffic signal at West 12th and Bowery streets.

At a July 30 CAC meeting, committee member Marissa Solomon said she doubted the measures would be enough.

“Two new traffic lights and some new stripes, is that really going to be able to handle what your own report says is going to be a complete breakdown in traffic?” she said.

Kovid Saxena, a practice manager at advisory firm TYLin, which is working with The Coney on traffic mitigation, pushed back on the “total breakdown.”

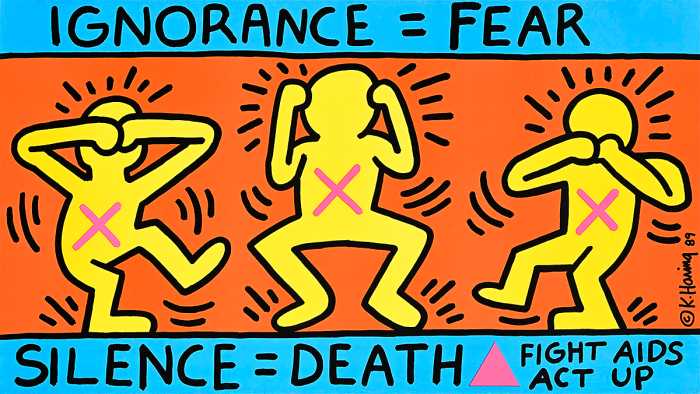

Saxena emphasized The Coney’s plan to incentivize employees and guests to take public transportation to lower the number of people driving to the casino. That plan includes offering discounted or free round-trip subway fare to visitors and employees and encouraging the MTA to run more express trains to Coney Island.

When asked if The Coney has spoken with the MTA and New York City Transit about those plans, Peter McEneaney, executive vice president at Thor Equities, said they had, and claimed the MTA was “tremendously excited” about the extra visitors the project would bring, and “would be supportive” of running more express trains.

“They haven’t finalized anything because this project is still in its infancy, but they would be supportive of an express subway service, which we’ve talked about,” he said.

He said The Coney will also advocate for the long-discussed but ill-fated ferry to Coney Island.

“I feel like there’s a lot of confusion in the community,” Scarcella-Spanton said. “It feels like some residents might think, If they come, we can have a ferry. How could you partner to be supportive of an oceanside ferry?”

Former Mayor Bill de Blasio said he would bring the New York City ferry to Coney Island in 2019. In the year since, the city’s Economic Development Corporation has said building a ferry landing on the ocean could cost up to $150 million. In 2022, the city axed its plan to build a ferry stop in the Coney Island Creek, citing issues with dredging as well as community opposition.

Last fall, Council Member Justin Brannan — who is also on the CAC — introduced a bill that would require the city to study the feasibility of a Coney Island ferry.

McEneaney said EDC should complete a new feasibility study for the oceanside ferry, then said The Coney would “figure out how to advocate for it.”

Parking problems

The Coney would include 1,500 parking spots on-site, per its application materials, but predicts that casino-related parking demand would top out at 2,346 vehicles on weekdays and 2,412 vehicles on Saturdays, requiring between 846 and 912 off-site spots.

A few thousand parking spots exist on the street and in parking lots within a .5-mile radius of the proposed casino site, per the EIS, and they would be sufficient during weekday mornings and afternoons.

But 90% of available offsite parking would be taken on weekday nights, and 88% overnight. On Saturday afternoon, an anticipated 94% of spots would be occupied, and demand for parking overnight on Saturdays would rise to 106% capacity of available spots.

Solomon pointed out that several of the off-site parking lots identified in the EIS are slated for development, and won’t be accessible in the future. Another lot belongs to the local DMV, she said, and isn’t open to the public.

Saxena said the EIS functions “like a stress test,” and shows the worst-case scenario, not necessarily the most likely one. While there likely will be a shortfall in available parking, he said, it will not be as severe as what’s described in the study.

The team believe more express trains and discounted subway fares would decrease vehicle trips to and from the casino by 27%, though neither of those measures are set in stone. The Coney also plans to run shuttle buses to the casino from Manhattan and the major airports, said Thor Equities COO Melissa Gliatta, hopefully reducing vehicle traffic further.

“Depending on a ferry that I’ve been hearing about as long as I’ve been working in government … and the increased subway ridership is hard,” Scarcella-Spanton said. “And it’s going to be hard for the residents to accept that as a reality for their traffic.”

What comes next?

The July 30 CAC meeting was an organizational meeting without opportunity for public feedback. The committee is expected to hold at least two additional public meetings before Sept. 30, the details of which will be posted online.

The CAC must vote to approve or disapprove the application by Sept. 30. Only projects with a two-thirds vote in support will be considered by the Gaming Facility Location Board for a license