The federal government is no longer paying for most COVID-related health care, leaving patients to deal with high bills for tests and vaccines that will likely discourage them from seeking care, and health care workers scrambling to continue providing what for the past two years many had started taking for granted.

Congress recently reached a deal to budget $10 billion for COVID-related care in the coming fiscal year. That’s far short of the $22.5 billion that President Joe Biden and congressional Democrats sought; Republicans, who throughout the pandemic have sought to downplay COVID-19 and engender distrust in science, wanted no further funding.

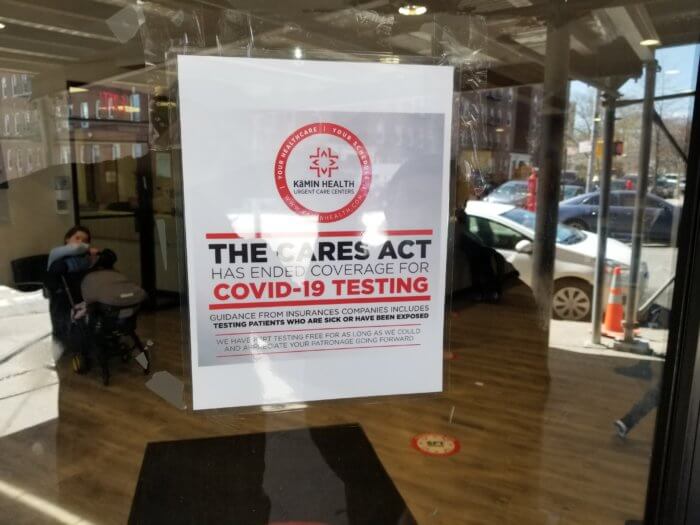

But some of the most significant funding for COVID-related care already dried up weeks ago: a program by the Health Resources Services Administration (HRSA) paying for COVID tests, vaccines, and related care expired on March 22, leaving most anyone wishing to get preventive or acute COVID care to either finagle with insurance or pay out of pocket — essentially, reverting COVID care to the labyrinthine system used in the rest of American health care.

The program, which spent about $20 billion over two years, reimbursed health care providers for the cost of tests, vaccines, and the like.

A spokesperson for New York City Health & Hospitals, the city’s public hospital network, said that tests and vaccines will still not cost any money out of pocket and that the system has no plans to change that, though did not specify where the money is coming from now.

“At NYC Health + Hospitals there continue to be no out-of-pocket costs for Covid tests or vaccines for any New Yorker regardless of their immigration or insurance status,” said H+H spokesperson Chris Miller in an email. “We have no plans to change this as we want everyone to get vaccinated and remain healthy!”

But the rule change is profoundly impacting the ability of small, private neighborhood clinics to provide the level of COVID care that patients have gotten used to over the past two years.

“The co-pays, the deductibles, they’re starting to crack down,” said Yosef Hershkop, the manager at Kamin Health’s Crown Heights Urgent Care at Kingston and Lefferts avenues. “It’s kind of like a nuclear bomb has fallen on America’s doctors.”

Hershkop said that when HRSA shut down the program, his clinic was unable to submit any reimbursement claims even for care provided before the cutoff deadline. Kamin Health continued providing the tests for free for the next two weeks, but this week had to start charging $75 for a rapid antigen test and $125 for a PCR test, with fees covering test sourcing, lab fees, and labor costs for administration.

Urgent care behemoth CityMD has also announced that it will start charging for COVID-19 related visits.

Throughout the pandemic, many insured customers at testing sites had not provided their insurance information at front desks, knowing that the care was covered anyway; insured patients now have to fill out mountains of paperwork so that their insurance will cover their test. Uninsured patients are either out of luck, or must break the bank to keep track of their health.

“The way to reopen is to tell people that if you’re at all sick to be responsible,” Hershkop said. “But right now we know, no one’s paying $75 for a test. Even well-off people just won’t do it.”

The change was abrupt and unexpected for providers, Hershkop said, but even more so for patients, some of whom have been verbally abusive toward staff telling them of the change. Some write emails afterwards confused about being charged, while some leave 1-star reviews on Yelp, Hershkop told Brooklyn Paper it’s probably only a matter of time that someone is physically assaulted.

A discouraging development

Even more worrying, though, is the impact that the change will probably have on people’s likelihood to seek COVID care. The program was initiated in the first place because the government sought to “bend the curve” and prevent the spread of the disease which has now killed over 40,000 New Yorkers, and in doing so resolved to eliminate the cost-barrier that prevents many Americans from seeking necessary health care.

But now that the government has stopped covering the bill — and as officials of both parties portray the pandemic as on the wane — fewer people are affirmatively seeking COVID care, even as cases begin to rise again due to the BA.2 subvariant of omicron.

“Especially now that they find out they’ve gotta pay out of pocket, fewer are coming in the door now,” said Zach, a medical provider at Crown Heights Urgent Care who declined to give his last name. He suspects that more people seeking COVID care from here on out will be those with clear COVID symptoms, and even they would be less likely to show up.

Even people with insurance may be out of luck come next week, if the feds don’t renew a state of emergency that expires on April 16. That’s because the state of emergency requires insurance providers to cover COVID-19 testing; if the state of emergency lapses, it’s anyone’s guess.

Rabbi Levi Telsner, who was visiting urgent care due to a foot injury, said that the government’s policy change would “absolutely” discourage him from regularly getting COVID tests.

“It’s not very happy that you have to pay $75 or $125 for a test,” Telsner said. “I have to fly soon to Chicago, I don’t know if I need one, but if I need one it’s gonna be very expensive.”

Dee Santana, a freelance makeup artist from Crown Heights, said that throughout the pandemic she has been an “obsessive” tester, both for her own personal health and because many on-set jobs require negative tests. Some jobs would test on-site, while others require a PCR in advance.

But now, she is in a state of limbo over whether her professional and personal need to regularly test will break her bank.

“Any person should be able to get tested at any time,” Santana said. “It’s gonna have an insane impact.”

‘The dumbest way to say America’s back’

The feds’ move may also prove counterproductive from a financial standpoint, Hershkop postulates: if there’s another wave, and the government is not paying for testing, many people will stay home rather than seek a test. While the impact will likely be mitigated somewhat by the state and city distribution of millions of at-home tests, those are notably less reliable. As a result, with fewer people affirmatively seeking care, more and more patients may seek care at an emergency room, which is far more expensive.

“Every single patient who came here to get a COVID test, the government got a good deal out of us,” Hershkop said. “Because we were screening that person to make sure they don’t end up in the ER, or only end up in the ER if really needed. We’re saving the government money, I’m confident about that, and we’re saving the insurance companies money. So many people won’t get a test and they’ll just get sicker and wait.”

“One day in the ICU,” he noted, “you could pay for 1,000 COVID tests with that bill.”

During the Omicron wave this winter, positive tests and positivity rates skyrocketed to heights above any seen prior in the pandemic. While Omicron is highly contagious, what’s also undeniable is more people got tested during Omicron than any other point in the pandemic: on Jan. 7, the day that cases peaked in New York State, over 425,000 people got tested. These days, an average weekday will see only 100,000 or so tests performed.

Since New York doesn’t record home test results in its official data, and with money acting once again as a barrier, the next wave may not be reflected fully in the data — and it’s possible that that’s happening right now.

“We’re gonna prepare for another wave, another variant, it’s just never gonna end,” Santana said. “And now even worse, people are already hesitant to be on top of it, people are just not gonna pay out of pocket.”

Hershkop suspects that the funding lapsed as part of government’s campaign to present New York and America as having successfully combatted the pandemic, and to reopen and return to normal. But at the end of the day, it may serve as yet another example of America failing to learn from its mistakes.

“This is the dumbest way to say America’s back,” Hershkop said. “It’s outlandish.”