It was 11:30 p.m. on May 30, 2000, when a nurse came into his room at Columbia Presbyterian Medical Center and told him a heart had just become available.

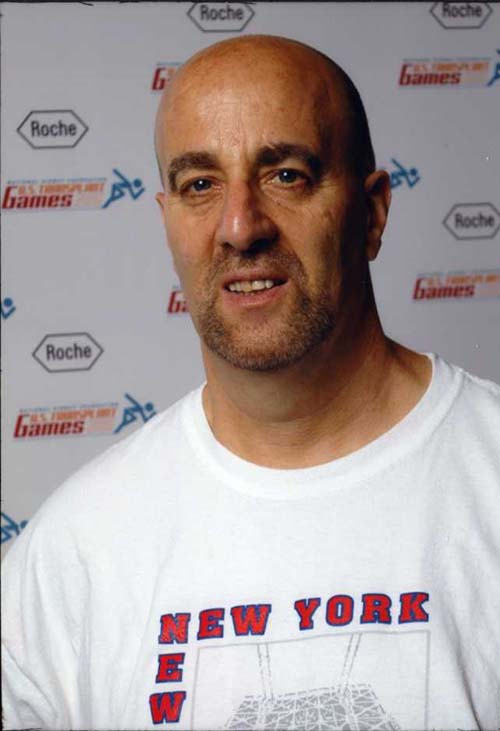

At that point, Stephen Feldheim – a father of four from Windsor Terrace who was suffering from congestive heart failure and cardiomyopathy, the deterioration of the heart muscle – had been waiting for a transplant for more than six months.

A few weeks before, he was told he would die in two to three days, but a temporary experimental treatment bought him some time.

When he heard the news about his new heart and lease on life, “I barely squeaked out, ‘Call my wife,’” he recalled.

“And then I sat there and cried for a half-hour straight.”

It was the beginning of a long journey back from the brink for Feldheim, who will soon compete in the 2008 Transplant Games starting July 11 in Pittsburgh.

He has won two gold medals in bowling, but will compete this year in basketball, discuss, shot-put, and the softball-throw.

It will be Feldheim’s fourth time competing in either the U.S. or World games, both of which are biennial and rotate so that there are games every year.

Anybody who has received a heart, kidney, liver, bone marrow, or pancreas transplant is eligible. Most of the competitions are broken down by gender and 10-year age groups.

“It’s just great to be able to go out there and do these things again,” said Feldheim, a computer database administrator who works for New York City. “Just to be in this position, at this age, from a stretch when I couldn’t even get out of bed – it’s thrilling.”

Sports have always been a big part of Feldmeim’s life, but before the Transplant Games, most of his involvement was more recreational than competitive.

Because his father had heart trouble, he always made a conscious effort to stay active, whether it was playing sports or walking from Windsor Terrace to his office at MetroTech Center.

But over a period of three to four months around a decade ago, he started to feel progressively fatigued on those walks.

“That’s how I first noticed something was wrong. And within a year and a half, I went from totally healthy to almost unable to walk,” he remembered.

In the period after he was diagnosed, he tried many prescription drugs. Most worked initially but lost their effectiveness as time wore on, as Feldheim went from 220 to 140 pounds.

The nadir came in April of 2000, when Feldheim was on death’s doorstep with no sign of a new heart in sight. But the installation of a Left Ventricular Assist Device, an experimental treatment, kept him going for a while.

Six weeks later, on Memorial Day, a 16-year-old girl suffered a brain aneurysm and died. As is always the case with organ donations, one family’s tragedy became another’s miracle.

“She sounded like such a wonderful person – she did a lot of charity work,” Feldheim said of the girl, who he only knows by her first name, Jamie Lee.

Interestingly, organ donations often come on the holidays because of the higher incidence of auto accidents.

“I remember all of us [in the hospital waiting for organs] had this morbid sense of anticipation on the big holidays,” Feldheim said, recalling the conflicted emotions inherent in receiving an organ.

After an eight hour operation, “I woke up and felt more alert than I had in 10 years,” he said.

He was out of the hospital in eight days, and by the end of the summer, he was back to playing softball in Prospect Park.

These days, Feldheim feels good, for the most part. But he has to contend with muscle atrophy, bone loss, and the effects of the immunosuppressant drugs he takes to prevent his body from rejecting his new heart, which weakens his immune system and causes some fatigue.

“It’s definitely a fair trade off,” he points out with his trademark humor.

In terms of his long-term prognosis, current statistics say 75 percent of heart transplant recipients survive five years or more. But as Feldheim is quick to point out, these statistics are always at least two years old and do not account for the rapid pace of medical progress in the interim that would paint a more optimistic picture.

“The way I’m treating this is, ‘Hopefully, I’ll live a long time.’ I’ve run into people at the hospital who are out 15 to 18 years,” he said.

Since his transplant, Feldheim and his family have become very active in organ donation programs. He volunteers at New York Organ Donor Network, and frequently visits patients awaiting transplants at Columbia Presbyterian.

“When I was in the hospital I found these visits from other healthy post-transplant patients very inspiring,” he said.

And of course he has the games. In addition to the thrill of the competition, Feldheim says the event provides “a good support group. That’s definitely the best thing about them.”