Summer has ended, but not without having taught Brooklynites a lesson.

This was the hottest summer globally since 1880, NASA announced earlier this month. Temperatures reached and surpassed 92 degrees Fahrenheit in Brooklyn more than once — on July 5, due to a heat wave and effects from Canadian wildfires that reached the borough, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration weather radar, and way later, on September 7 and 11. July was the warmest month ever on record globally, according to Copernicus Climate Data.

“We will frequently see more climate records and more extreme weather events impacting society and ecosystems until we stop emitting greenhouse gases,” said Adria Schneck, deputy director of the National Centers for Environmental Prediction. “And even once we do, we will have to take actions to capture a lot of our emissions from the atmosphere. Temperatures won’t get back to what they were in 1991, before we saw a fast increase in carbon emissions that has set more CO2 in the atmosphere than in the rest of history, unless we implement many solutions that have been viable for years.”

Each summer, on average, an estimated 350 people die prematurely in New York City because of hot weather in between May and September, according to the 2023 Heat-Related Mortality Report. Seven heat waves — defined as two days or more of abnormally hot weather, caused by warm air trapped between the atmosphere and the ground without flowing — hit New York State per decade on average.

On those hottest of summer days, asphalt turns into goo, planes stay grounded, subway rails expand and buckle and the electric grid overheats — often forcing utility companies to ask customers to cut down on their usage to avoid blackouts. Without electricity, the city’s residents can’t run their air conditioners. During heat waves, the city opens up public cooling centers where New Yorkers can go cool off. But the cooling centers only open under particular conditions, and some city officials say there aren’t enough centers — especially in neighborhoods particularly vulnerable to high heat.

Sudden rains and summer storms have resulted in tens of thousands of deaths on every continent this year. Brooklyn is particularly vulnerable to flooding, which is expected to get worse in the near future — also thanks to climate change. In July, after a “microburst” thunderstorm downed trees and power lines in Bensonhurst, the commissioner of the city’s Office of Emergency Management said the sudden and destructive storm was a “prelude of climate change.”

Air quality this summer was also hazardous, forcing organizations to cancel outdoor events as authorities urged New Yorkers to stay indoors and wear masks to protect themselves from dangerous air. It wasn’t only because of the heat and the fires, but the 4th of July fireworks greatly added to the burden according to the Environmental Protection Agency’s AirNow map.

Advocates have proposed growing the area of the city covered by trees from 22 to 30% by 2035 to deal with urban heat. But to do so efficiently, trees have to be planted strategically, and it’s not clear where the money to plant and maintain those trees would come from.

The state is still committed to reaching net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. Yet, climate experts from George Mason University estimate that, under a medium-carbon-emissions scenario, temperatures will reach 106 degrees Fahrenheit more than once a decade in North America. Under a high-emissions scenario, it’ll be every two years. Without effective action, in a carbon-dioxide-rich future, we will get a 112-degree day once every seven years.

A new report by Con Edison predicted that the city will experience up to 17 days a year with temperatures of 95 degrees Fahrenheit or higher, and up to 27 such days by 2040.

Mayor Eric Adams signed a plan to “Get Sustainability Done” last April, seeking to protect New Yorkers from flooding and make the city greener with buyouts for flood-prone properties, free solar arrays installed on 3,000 homes, 1,000 electric car chargers throughout the city by 2025, and increased freight deliveries by bike and boat instead of on-road trucks. In alignment with the state climate law, the new plan aims to run the city on gas-free electricity by 2040.

“We’ve seen what climate chaos can do to our city,” Adams said at a press conference on the solar-paneled roof of Frank J. Macchiarola Educational Complex in Sheepshead Bay, when the plan was signed.

The last two administrations signed plans that included slashing greenhouse gases, accommodating New York’s growing population, switching from fossil fuels renewable energy and pushing for fewer cars on the road.

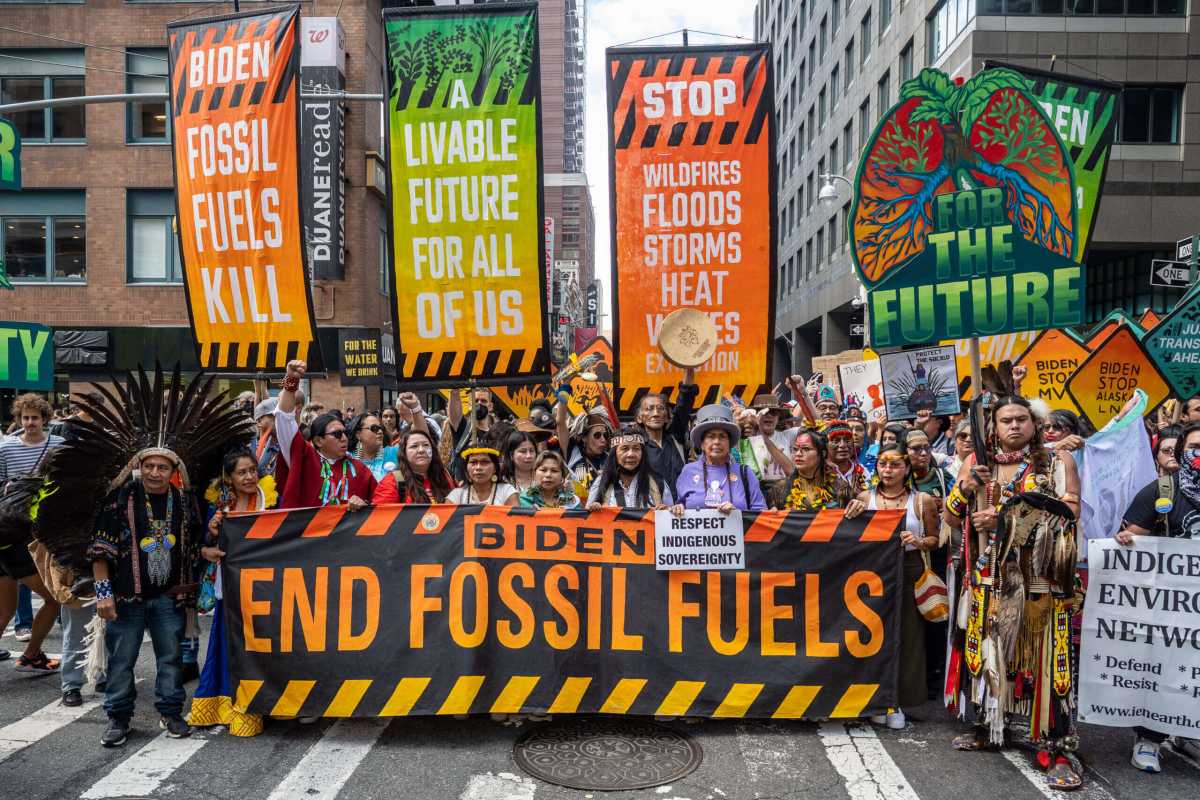

“We just can’t leave it to them anymore,” said Rebecca Nungo, Environmental Action NY board member. “Politicians and academics are vital to fight this climate crisis. We need the knowledge, the innovation, the authority and the resources they provide, but we are the strength. There are so many people living in this city and in the world. Corporations have caused a lot of damage, but we certainly play a part and we can’t wait until they decide to make an effort. We need to find ways to contribute now.”