August marked the 100th birthday of James Baldwin, one of the most important authors in American history. The Brooklyn Public Library, like many cultural institutions, wanted to mark his centennial somehow.

They weren’t quite sure how until Jakab Orsós, BPL’s vice president of arts and culture, got an email from someone who claimed to be a Turkish curator with a collection of never-before-seen images of Baldwin from the decade he lived in Istanbul.

“I thought it was a scam,” Orsós said. “But I said, send me some images. Within a day, in my mailbox, there were 10 jaw-dropping photos of Baldwin in Istanbul.”

Those photos, it turned out, were taken by Sedat Pakay, a Turkish photographer who befriended Baldwin in Istanbul and spent ten years snapping photographs of him. Orsós traveled to Hudson, New York, met Pakay’s wife, Kathy, and dove into the archives.

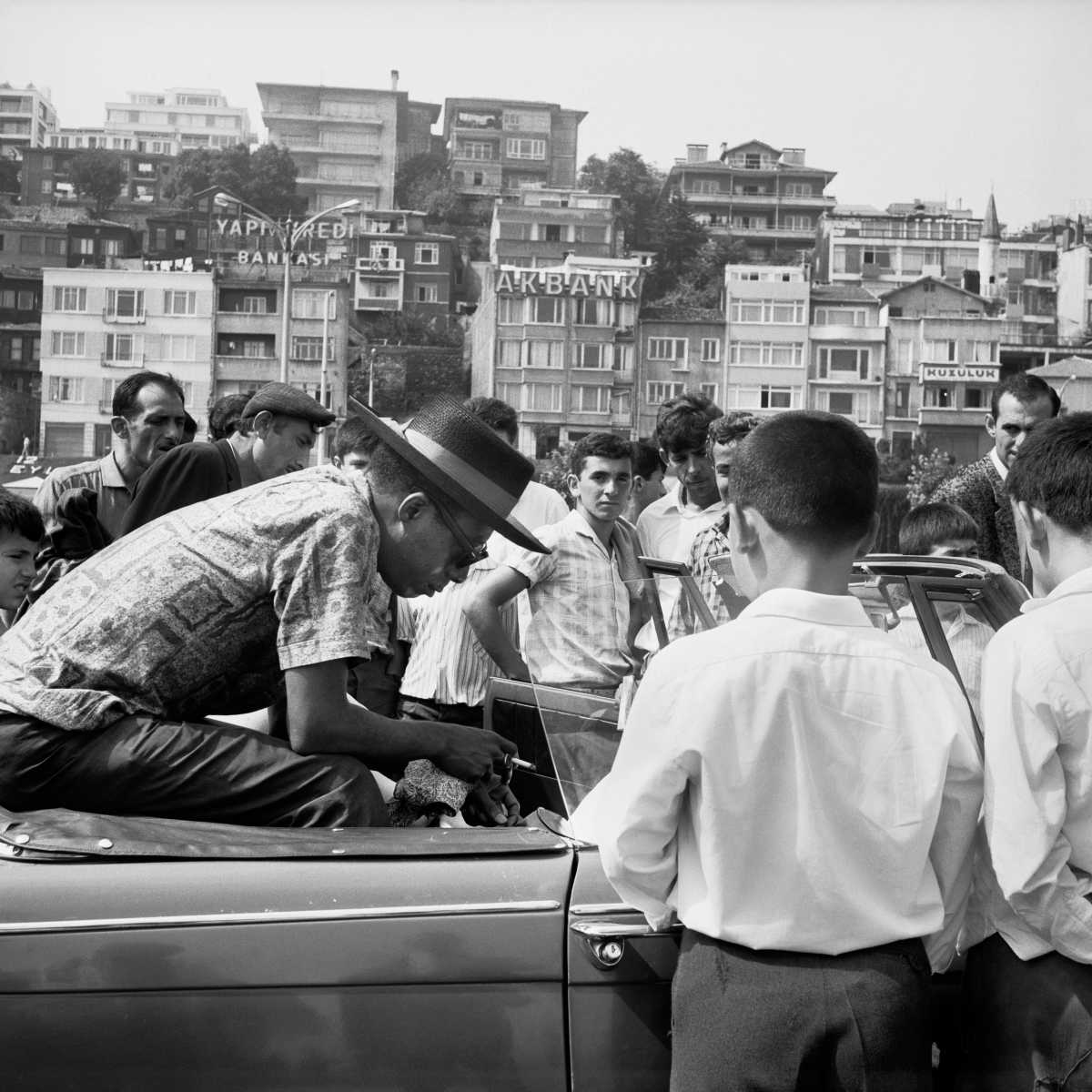

The work is now on display at BPL’s new exhibit, “Turkey Saved My Life, Baldwin in Istanbul 1961-71,” which opened on Dec. 12. Housed in the lobby of the main branch on Eastern Parkway, the exhibit contains dozens of Pakay’s photos, including several that have never been seen by the public before.

Not much is known about Baldwin’s time in Turkey, Orsós said, and many people don’t even know he spent time there — the decade is overshadowed by the many years he spent in Paris.

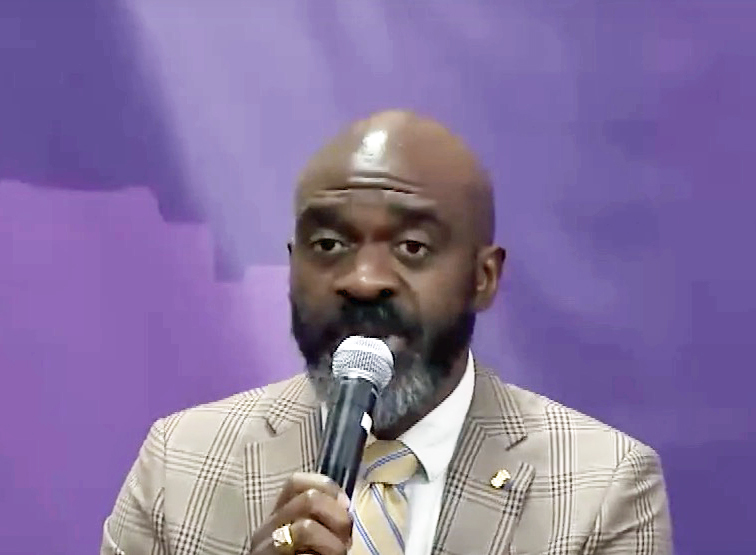

“He lived almost for 10 years in Istanbul, seeking something,” Orsós said. “That was my biggest question throughout the curation, ‘What exactly is this amazingly important writer and introspective Black, gay intellectual seeking?’”

What he was seeking, Orsós feels, was a sense of acceptance outside more traditional Western society — Baldwin had dealt with a lot of hardship and prejudice in his native New York City and in Paris, where he lived for many years, and Istanbul was something new.

He found community and friendships in the city, Orsós said, and was “amazingly productive.” He published two novels while he lived there, “Another Country” and “Tell Me How Long the Train’s Been Gone,” wrote dozens of essays, and directed a production of the play “Fortune and Men’s Eyes.”

“Baldwin metabolized food, music, culture, theater into work that was new but was also American, and let America see itself from a different place,” said Magdalena J. Zaborowska, an American History professor and Baldwin scholar, at the opening night of the exhibit. “It was also the place where queerness became real to him in very new, sometimes very surprising ways.”

David Leeming, Baldwin’s longtime friend and assistant, said the author was a “born adventurer.”

“When he came to Turkey, it was not just to find a quiet place to work, although that was it too,” Leeming said. “It was to insist that he learned something about the culture, something about the people there, and to be excited by them, which he was.”

The photos on display at BPL capture Baldwin’s day-to-day life in Istanbul — walking through the city, pulling off his shoes before entering the Blue Mosque, sitting at his desk. Many show him laughing with friends at parties, in kitchens and on balconies.

“These are really emblematic images of this very well-known figure, a Black male, being thrown into this exotic surrounding, being there, feeling safe, but not belonging,” Orsós said. “This interesting dichotomy is so Baldwin, and so much engraved in his legacy.”

The photographs aren’t the only part of the exhibit, which will be on display until February. While curating the exhibit, Orsós learned that scholars had recently unearthed outtakes from a 17-minute video Pakay shot of Baldwin discussing racism in 1969.

A team at Yale is actively restoring the film, and it will be shown — alongside some Baldwin documentaries — in a “mini film festival” at BPL next month. Orsós is also planning a discussion of the author’s essays in February.

Something new is coming to the library’s permanent collection, too, an audio recording of “Fortune in Men’s Eyes.” The piece, set in a prison, explores homosexuality and loneliness, and Baldwin’s production featured mostly drag actors, with music by jazz musician Don Cherry.

It was a success — one that was shortly thereafter banned, then unbanned, by the Turkish government. Cherry’s score was presumed lost forever.

Until two years ago, when a cassette tape of rehearsals from “Fortune in Men’s Eyes” was found in Sweden. The tape was carefully restored and pressed on vinyl, and BPL was set to receive a copy for its collection days after “Turkey Saved My Life” opened on Dec. 12.

The Brooklyn Public Library, Orsós said, is a great place for the exhibit. It’s free, open to all, and easy to access — there are no tickets or barriers like there might be if it were hosted in a gallery. Many people will stop by just for the exhibit, he said, but some will discover it by accident, and that’s what he loves about the library.

“The library users, the researchers, people who are coming to do their passport photos, they’re going to walk into the show and lo and behold, learn something about a writer who they hopefully know, or maybe they don’t,” Orsós said. “They see a very expressive face, and maybe that’s going to bring them into this essential and charismatic life of James Baldwin.

“Turkey Saved My Life – Baldwin in Istanbul, 1961-71,” runs at the Brooklyn Public Library’s Central Library at 10 Grand Army Plaza through Feb. 28, 2025. Admission is free.