Brooklyn-based photographer Jon Henry has spent the last nine years in the making of his project “Stranger Fruit,” a book with photos of Black mothers from every state in the country, who worry about the safety of their sons in the hands of the police.

After his work traveled to galleries and shows in over ten states and three countries, The Kraszna-Krausz Foundation, the U.K.’s leading prize for original photography, shortlisted Henry’s publication among the Best Photography Book of the Year. The foundation says it recognizes creativity and rigor within the publishing industry, selecting books for their content’s historical and cultural quality and presentation. If he wins, Henry will be awarded £5,000 and major exposure internationally.

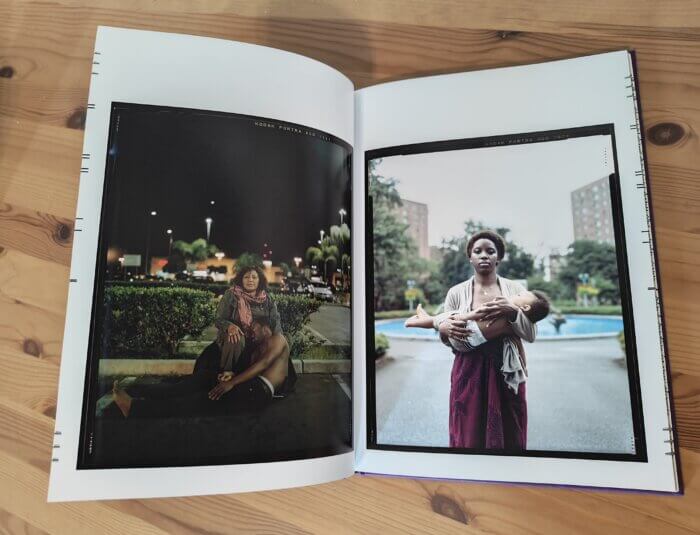

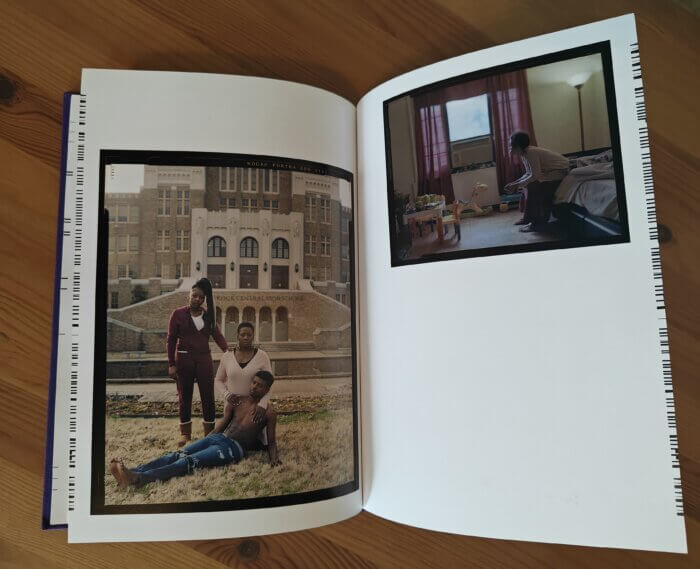

To create “Stranger Fruit,” Henry reached out to families in each state, and in specific Black neighborhoods, to pose them as if mourning their sons, calling out police violence that has historically resulted in the killing of thousands of young Black men and has left terrified mothers and incomplete families.

Henry took inspiration from Michelangelo’s famous sculpture, Pietà, in St. Peter’s Basilica in Vatican City, which features Mary holding her dead son, Jesus in her lap. He photographed Black mothers standing alone or accompanied by their youngest children, holding their sons’ bodies in front of landmarks or landscapes, sometimes sitting alone at home seemingly mourning, and used texts written by them that expressed their worry.

“The mothers in the photographs have not lost their sons, but understand the reality, that this could happen to their family,” Henry wrote in the book’s introduction. “The mother is also photographed in isolation, reflecting on the absence. When the trials are over, the protesters have gone home and the news cameras gone, it is the mother left. Left to mourn, to survive.”

Over 1,046 people have been shot and killed by US police in the past 12 months, according to data collected by the Washington Post, the second-most since the newspaper began tracking fatal shootings by officers in 2015. On average, police kill more than 1,000 people every year. Black Americans are shot at a disproportionate rate. They account for roughly 14% of the country’s population and are killed by police at more than twice the rate of any other ethnic group, which are also commonly faced with lethal violence from authorities.

Henry was one of TIME Magazine’s NEXT 100 for 2021. He has been recognized by the Silver Eye Center for Photography and Kodak, and his work was exhibited in South Korea, the Netherlands and Italy. Now, The Kraszna-Krausz Foundation selected ‘Stranger Fruit’ as one of the three finalists for Best Photography Book of the Year which has granted him a spot at Photo London, an international photography fair.

Henry is a native of Flushing, Queens. His interest in photography was sparked by his parents, who would carry a camera through all family vacations, he said. His dad used to take portraits of friends and relatives, and when he was in high school, Henry would bring disposable cameras to school to photograph his friend’s sneakers collections.

He grew into sports and athletics photography. He became a photography student at the New York Film Academy, where he now teaches several classes from Intro to Photography to Long Format and Long Time series.

“[The book] is an incredible accomplishment,” Henry said. “I’m a guy from Queens, New York, living in Brooklyn, making my work for the last nine years. And all of a sudden, people can experience it. There is a lot of pride in having people familiarize themselves with it. You never know how people can react to seeing those photos, but I’ve gotten so much out of what they’ve expressed to me. Teachers tell me how they share my photos with their students and so on.”

The picture that started it all portrays a friend of Henry’s and his mother in a church, surrounded by lit candles. That is the only photo in the book Henry didn’t shoot with natural light.

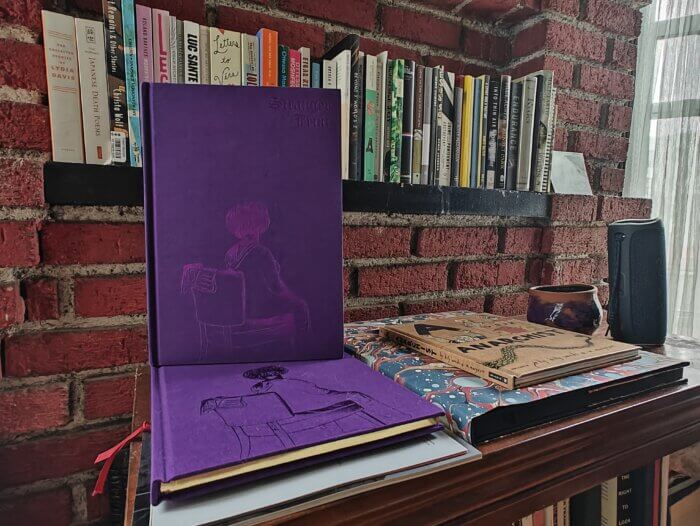

Three years after starting “Stranger Fruit,” it became evident to Henry that the project had to become a book. He decided on a purple velvet cover with an illustration of one of his photos, where a mother looks out the window, to make the body of work of 24 pictures, unique, even from the outside. The photography project evolved once he started bringing in texts from his photo subjects.

“I think that I’m powerful,” wrote one of the mothers. “And the look displayed in the moment of carrying my Black son, whom I prayed for and patiently waited to manifest in human form, was intense. It is the look of determination and a look that says, ‘Don’t f–k with this one!’ My eyes tell the story of a soul that would become warrior-like and completely changed if I ever had to see my seed’s eyes closed infinitely.”

In Brooklyn, some organizations are fighting against police violence from different fronts. The Brownsville Safety Alliance, a group of neighbors, city groups, police officers and members of the Kings County District Attorney’s office is focused on ensuring that fewer people are arrested and entangled in the criminal justice system. Save Our Streets in Crown Heights and Bedford-Stuyvesant works on changing local norms around violence and creating educational and employment opportunities to end gun violence, but as Henry points out, the crisis continues.

“It’s painful,” Henry said. “You are done with the work, but you still live with the work after all. People die, it can’t get more serious than that, but it gets overlooked.”