The corpse of the proposed Coney Island casino was still warm when its funeral began.

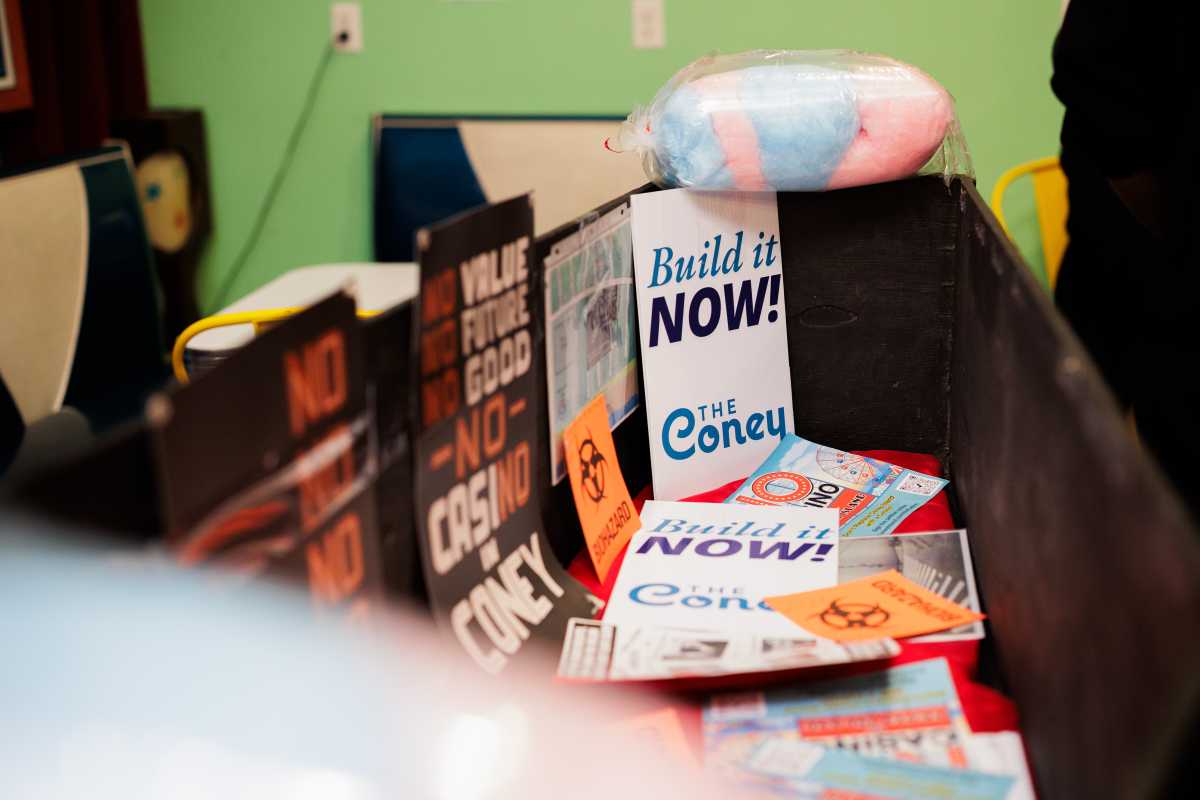

As locals filled the front room at Coney Island USA on the night of Sept. 29, Assembly Member Alec Brook-Krasny fake wept over a makeshift casket filled with “The Coney” flyers and cotton candy. People snapped photos of their middle fingers outstretched toward the coffin and scribbled not-so-fond notes in the guestbook.

Just hours earlier, the Community Advisory Committee had voted The Coney down 4-2, officially ending its bid for a state casino license. Council Member Justin Brannan, the chair of the committee and the first member to announce that he would vote against the casino, received a hero’s welcome when he arrived at the party.

When it came time for eulogies, lavishly-dressed pallbearers carried the casket into a packed auditorium and set it down in front of Adam Rinn, Coney Island USA’s artistic director and the master of ceremonies.

“We are here to mock [The Coney] as they have mocked us for three years,” Rinn told the crowd. “It took a group of dedicated grassroots activists to take down a multimillion dollar effort, which consisted of paid lobbyists, paid advocates. Lobbyists who pocketed thousands upon thousands of dollars to sell a pack of lies.”

The raucous funeral was a celebration for the Coney Islanders who had most vehemently opposed the casino, and marked the end of a long and divisive period in Coney Island history.

But The Coney left its mark on the People’s Playground and its residents — those celebrated the casino’s death and those who mourned it.

The life and death of The Coney

In late 2022, Thor Equities, a local development company owned by longtime southern Brooklynite Joe Sitt, said it would throw its hat in the ring for one of three new casino licenses set to be distributed by the state.

Together with the Chickasaw Nation, Saratoga Casino Development and Legends Hospitality, Thor proposed a $3.4 billion, 1.4 million-square-foot facility between Surf Avenue and the boardwalk, spread across several underdeveloped lots already owned by Sitt.

Developers said the casino — which would have included a hotel, convention center, restaurants and stores — would bring thousands of permanent jobs and year-round economic activity to the seaside community, which struggles in colder months.

When the bid was announced in 2022, Sitt said he was “committed to creating lasting prosperity for a community and its residents and turn Coney Island into a vibrant year-round destination for all to enjoy.”

The proposal proved immediately divisive.

Residents lambasted the project at a series of public meetings in spring 2023. Many worried a casino would overwhelm Coney Island’s infrastructure, drive up rent, and damage local businesses and the iconic amusement district.

Those meetings also marked the start of an often combative relationship between locals and the casino team.

Still, some felt good about the proposal. Its earliest supporters said Coney Island desperately needed the jobs the casino promised. Others said if the project should include funding for the boardwalk, jobs training, and transportation.

The Coney sweetened the deal, pledging to create a community trust fund, provide additional funding for local emergency services and help fund the theoretical Coney Island ferry if the casino were approved.

But things grew more contentious over time. Locals attacked each other and The Coney online. Drama at Community Board 13 reached new heights earlier this year as the board weighed a rezoning that would allow Thor to build larger, taller buildings if its license were approved.

Brannan voted to approve the rezoning when the application reached the City Council. At the time, he said it was his “responsibility to ensure that all stakeholders have the opportunity to make their voices heard on this matter through the Community Advisory Committee process mandated by New York State.”

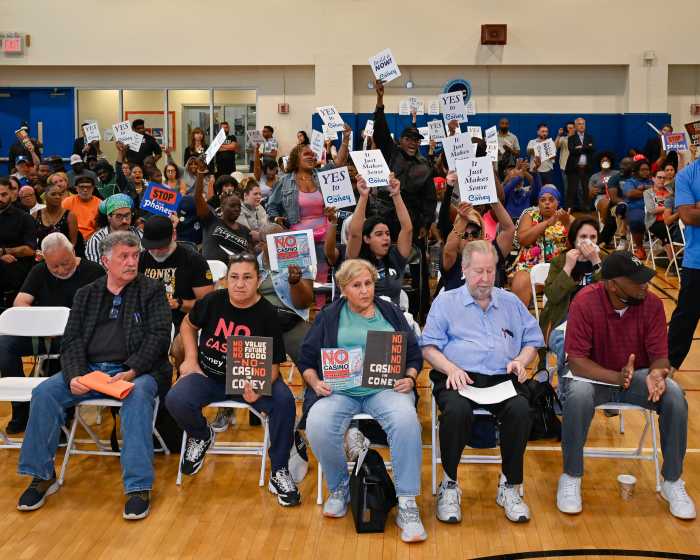

The two CAC meetings, hosted in late August and early September at the Coney Island YMCA, were hours long and packed to the gills.

Speakers from both sides were repeatedly shouted down, and one attendee told Brooklyn Paper she had been threatened with violence by a pro-casino advocate. At the second hearing on the night of Sept. 10, police stepped in to break up two separate physical fights, and rumors flew afterward that The Coney had bribed people to testify in favor of the project.

Just over 200 people spoke across the two CAC hearings. Roughly 140 were opposed to the casino, and just 60 were in favor.

A week before the CAC was set to vote, Brannan announced in an Op-Ed that he would vote against it. Three other members — Reynoso, state Sen. Jessica Scarcella-Spanton, and Marissa Solomon, who was appointed by Brook-Krasny — followed suit. On Sept. 29, they officially cast their votes, and The Coney was no more.

Locals grapple with fallout of a long fight

Some Coney Islanders said the battle over the casino, no matter how contentious, had been unifying.

“It united our community more than years and dozens of nonprofits and events could,” local activist Angela Kravtchenko said at the funeral. “We literally got united from Sea Gate to Brighton Beach, and I’m so excited to see our elected officials, from different backgrounds, they all voted no to this.”

Council Member Inna Vernikov, a Republican whose district includes parts of Coney Island, Sea Gate, and Brighton Beach, was vehemently opposed to the project and voted against the rezoning in the City Council. Brook-Krasny, also a Republican, was publicly against the project from the start, and appointed Solomon — an outspoken casino critic — to the CAC.

“This moment in history calls on all of us to step up, to reach across, to put aside our differences,” said Maxim Ibadov, a drag performer who appears at Coney Island regularly as Maxxim Fab. “I never thought I would be applauding a Republican Assembly Member as a queer person, but we were able to put aside our differences.”

Ibadov, who moved to New York from Russia in 2012, said fighting the development was critical not just for Coney Island’s artists, but for the large immigrant community who reside there and in nearby Brighton Beach.

“People who come from different walks of life, different generations, we speak different languages,” they told the crowd. “Yet the universal truths of justice, community, fairness, love, they outshined all of that. I hope this is a blueprint for how we move forward.”

Kim Cowell, who has lived in Coney Island for nearly 60 years, said she was “so happy” the casino had been voted down, and that she “met so many wonderful people” while fighting against it.

“Now we can promote Coney Island more, build more vibes, do more things, and we’ll still be able to do the Mermaid Parade and fireworks every Friday night during the summer,” she said. “And everybody just being together. It’s like one little community, it’s wonderful. I would never trade it for anything.”

Others felt differently.

Dick Zigun, the longtime “unelected mayor of Coney Island,” said he has been in favor of a Coney Island casino since the 1970s, the first time one was proposed for the nabe. When Thor announced their plan, he threw his weight behind it, and was eventually being paid by The Coney for “public outreach,” according to its gaming license application.

The backlash Zigun faced from neighbors was “horrible and intimidating,” he said.

“I personally feel like on social media, at one point, people were advocating violence against me,” he said. “It was awful.”

Zigun founded Coney Island USA and the Mermaid Parade, but parted from the organization in 2021.

“I’ve got a long history of speaking up, everybody knows where I’m coming from,” he said. “I think a lot of other people were intimidated, for sure.”

Erica Turner, who helped lead the charge against The Coney, grew close with her fellow organizers during the three-year campaign, she said. Simultaneously, she was growing frustrated with the casino’s supporters and developers.

“I made a lot of enemies during this time. A lot,” she said. “It impacted us in a negative way, because we’ve seen how they were coming out, trying to buy the people.”

Marie Mirville-Shahzada, the executive director of Alfadila Community Services, saw the casino as “an opportunity to bring much-needed investment into a community that has been neglected for far too long,” she told Brooklyn Paper. She vocally supported the project for years.

At the Sept. 10 CAC hearing, she said her position had come “at a personal cost.”

“My children, my businesses, my nonprofit organization and even my faith have been verbally attacked,” she said at the time. “I have been slandered on social media, boycotted, and blacklisted by those who oppose.”

With the casino off the table, Mirville-Shahzada feels Coney Island needs “a period of healing.”

“The community needs peace and understanding to mend relationships that were strained during this process,” she said. “My hope is that future initiatives will continue to bring positive investment into our neighborhood — in ways that unite rather than divide us.”

For some, that mending came quickly. Minutes after the final CAC vote at the Coney Island Public Library on Sept. 29, Joe Packer — who had organized in favor of the casino — greeted his longtime friend and casino opponent Lucy Mujica Diaz.

Mujica Diaz said some of her relationships were soured by the fight, but that she worked to keep things civil as often as possible

“I’m going to use Joe Packer as an example. Thirty years we know each other, 30 or 40 years,” she said. “We were on both ends, but we made sure that our friendship and relationship continued, because he had his passion for the community and I had mine, and that’s what friendship is about.”

Coney’s post-casino future

As thoroughly as Coney Islanders clashed over the casino, most could agree on one thing: The People’s Playground needs a boost.

The median household income in CB13 is $47,177 per year, according to city data, the citywide average, and the poverty rate is 26.3%. Employment among Coney Islanders ages 16-64 is lower than it is citywide, and when the beach and theme parks close in the colder months, the boardwalk is often deserted and local businesses shuttered.

Zigun said Coney Island’s specially-zoned entertainment district has been cut down in size significantly since the 1960s, and feels the priority should be on rides and entertainment.

“Coney Island needs a big project, it needs to be built on Thor Equities property, which is the only large property available, like it or not,” he said. “My fear is that the people who are delighted they killed the casino were going to want to kill other things and advocate for housing or senior center things that would be excellent for the community, but not on that property. There’s so little acreage left for the amusement and tourist area.”

In the immediate future, he said, the community might be best off looking for “common ground” in small projects that would benefit residents and tourists, like a movie theater or bowling alley.

Thor Equities did not return a request for comment.

When Brannan took the stage at the funeral, he said Coney Island shouldn’t be a neighborhood “that says no to everything.”

“But we want to be a place where we say yes to things that complement our neighborhood and make our neighborhood better and stronger, not cannibalize our neighborhood,” he said.

On Oct. 6, Brannan hosted a “community conversation” about the nabe’s next steps. The Coney Island Neighborhood Revitalization corporation hosted a similar event in partnership with the Pratt Institute a few weeks later.

Working with Thor Equities is inevitable, Brannan said at the funeral, since the company owns so much land. But he felt locals had the upper hand after shooting the casino down.

“Let’s harness that power, let’s not let it end tonight,” he said. “Think about what we really want, a water park, an artist district … there’s a million things we can do, and these guys can still make a boatload of money off it, but do it in a way that they’re not going to bleed us dry and suck all of the goddamn oxygen out of the last egalitarian playground in the city.”