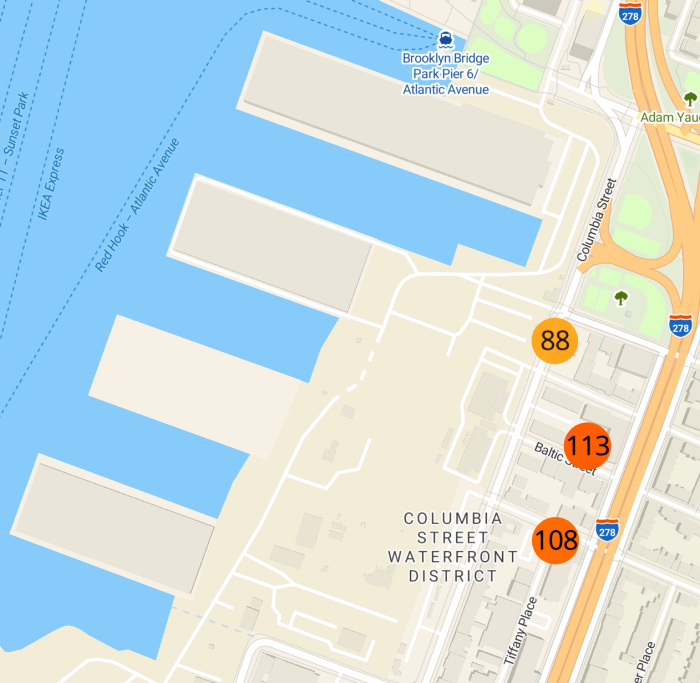

Columbia Street Waterfront District residents and politicians are demanding the immediate shutdown of a city-owned concrete recycling facility they say is filling the air with hazardous dust.

Dozens of locals picketed outside the Columbia Street plant on Wednesday, waving signs that read “Shut it down” and “Protect our health!! Protect our community!!”

For nearly a year, the Department of Transportation-run facility has plagued the nabe with noise and concrete dust, picketers said, and the city hasn’t done enough to help, despite repeated requests from locals and elected officials.

“This is something that right off the bat was toxic and right off the bat wasn’t working,” said Assembly Member Jo Anne Simon. “Everything that they have tried to alleviate the problem isn’t working … So when nothing is working to fix it, you have to shut it down.”

The facility reprocesses old concrete to be used in new projects, an environmentally-friendly endeavor that reduces construction waste. It was temporarily moved from the South Brooklyn Marine Terminal to the Columbia Waterfront District last year to make way for the construction of offshore wind infrastructure at the terminal, according to the DOT.

While concrete recycling is eco-friendly, it’s also loud and dusty, and the facility sits directly across the street from a residential neighborhood. Since it opened last February, residents said they have watched concrete dust blow across the street and into their homes, especially on windy days.

“I’ve had grey dust in my home daily since February 2024,” said resident Geraldine Pope, in a statement. “I needed to install air purifiers in every room. I wake up in the morning with a dusty cough. I cannot open my windows anymore because the air is now toxic to me. How could our city betray the safety of our homes?”

Over the last 30 days, average air quality in the area has been “moderate” by Environmental Protection Agency standards, according to PurpleAir, presenting some risk to those sensitive to air pollution.

However, sensors pick up regular spikes. On the afternoon of Jan. 17, two sensors were registering air that was “unhealthy to sensitive groups,” including children, seniors, and those with health conditions.

Local elected officials have been in conversation with DOT and the mayor’s office about the plant since last year, said Council Member Shahana Hanif, and the department had responded to their concerns and implemented some extra measures to keep dust contained.

But the situation didn’t improve, and in November, pols for the first time urged the city to close the facility entirely.

In a Dec. 12 letter shared with Brooklyn Paper, DOT commissioner Ydanis Rodrigurez called the facility “critical,” and said while DOT is actively searching for a new location for it, they had yet to find one.

The department uses sprinklers and water trucks to keep piles of concrete aggregate wet to keep dust down, he said was working to do more.

“Operations at this facility will cease for the season once the temperature is consistently in the 30-degree range,” he wrote. “When operations resume in March, the agency will have secured a new system to enhance wetting of the piles, which reduces dust.”

The facility was still active in early January, Hanif said, when a constituent sent an “egregious” video of dust in the air on a windy day.

“You can’t say, ‘No, this is not dust,’” Hanif said. “This is happening, and whatever mechanism you have in place is not efficient.”

Short-term exposure to concrete dust can result in eye and respiratory irritation, according to OSHA. Longer-term, it can cause lung injuries and disease, and local residents — and parents of children at P.S. 29 on Henry Street, a few blocks from the facility — are worried about their health, Hanif said.

Despite repeated letters from pols and complaints from residents, DOT and the mayor’s office have shown a “lack of interest” in the issue, Hanif said, and a lack of transparency about why the facility has to stay on Columbia Street and how it might be impacting the neighborhood.

“No one — not anyone affiliated with the DOT, not any of our local elected officials, nor anyone in the neighborhood — can make a valid argument for why this concrete plant should be located where it is,” said local Molly Pearson, in a statement. “No one has dared to vouch for its safety, and no one disputes that it endangers our collective health and quality of life. The city, our officials, and the DOT need to shut this plant down immediately. It is inexcusable to have it in the middle of a residential neighborhood.”

In conversations with DOT officials, Hanif added, they have said that if the facility is shut down, it might be relocated to another residential neighborhood.

“We don’t want you to move it to somebody else’s neighborhood,” Simon said at the Jan. 15 rally. “Shut it down until you can find the right place to do this that will not have a negative health impact on other people.”

In an email, DOT representative Mona Bruno said the facility is an important part of DOT’s sustainability efforts.

“We are taking all the necessary steps to keep the public safe — though in response to community feedback, NYC DOT has taken new measures to decrease the size of the recycled material piles in this plant and further reduce dust and noise,” she added.

Correction 1/21/25, 3:26 p.m.: This story previously misstated the name of the plant’s original location — it was moved from the South Brooklyn Marine Terminal. We regret the error.