New York’s congressional, state senate, and assembly districts are set to be redrawn this year, and for the first time in history, everyday New Yorkers have had the chance to weigh in on how they think the districts should be drawn up.

The New York Independent Redistricting Commission, the entity tasked with redrawing the state’s political boundaries, has held a series of hearings so far, including one for residents of Brooklyn and Staten Island on July 29.

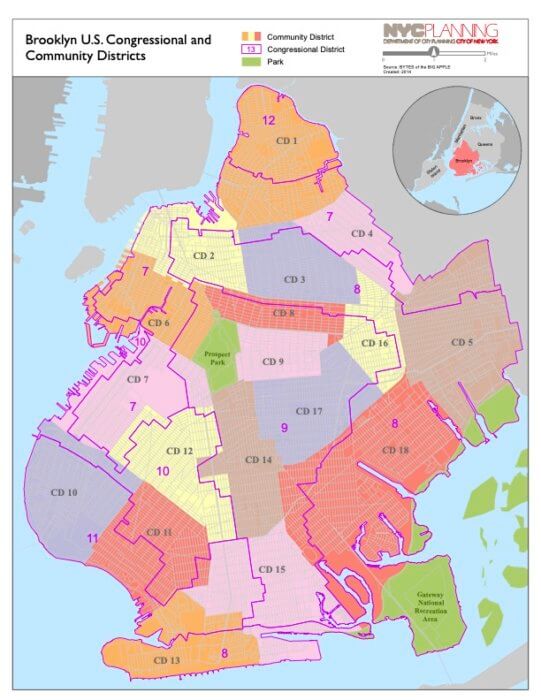

The process, which takes place every ten years following the census count, has long been set up to benefit incumbent candidates and political parties, with districts carved up into oblong shapes, often splitting up neighborhoods into multiple districts, known colloquially as gerrymandering. Following the 2020 census, New York state will also lose one congressional seat.

The redistricting commission was formed after a 2014 referendum with the intention of including more New Yorkers in the redistricting process. Made up of 10 appointed members — five Republicans and five Democrats — the commission has the stated purpose of being non-partisan, but has received criticism from good-government groups for the partisan nature of its appointees.

Gerrymandered districts abound in Brooklyn, with odd-shaped territories stretching across multiple communities and moving snake-like down narrow corridors, leaving residents in those neighborhoods without one clear representative to take their issues to.

Gerrymandered districts also present challenges from a governing perspective, according to one south Brooklyn elected official who said that, when districts span large, sliced up swaths of different neighborhoods, it weighs on elected officials’ abilities to serve all their constituents.

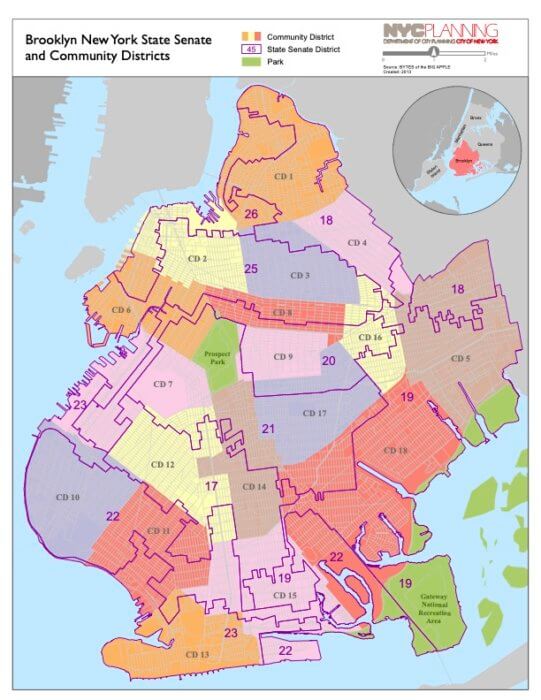

“It’s tough to have such a widely dispersed district because you only have so much staff, so many hours in a day, it’s hard to really be a good advocate for and representative of a district that spans such a wide geographic area,” said state Sen. Andrew Gounardes, whose oblong district stretches from the shores of the Verrazano Narrows to Marine Park. “It’s very hard for me to be in Bay Ridge, Gravesend, and Gerritsen Beach all within the span of an hour, it’s impossible to drive that. It’s very hard to adequately be present in each one of those neighborhoods the way that a representative should be.”

Gounardes maintains that his district was clearly carved out with the benefit of his predecessor, former Republican state Sen. Marty Golden, in mind, resulting in a puzzle-piece shaped district that contains small slivers of some neighborhoods, and wide swaths of others that leaned right.

“With the population density of Brooklyn being what it is, there’s no reason why, in an objective-speaking world, that my district would extend from the Narrows waterfront all the way to Flatbush Avenue, but cut out about half the population that lives in between that span,” Gounardes said.

‘That’s what makes a democracy a democracy’

When neighborhoods are subdivided into several different districts, it can also make it harder for locals in those communities to get the services they need from their elected officials, or to harness political power.

This is currently playing out in Sunset Park, which is divided into a whopping five state senate districts between the waterfront and Eighth Avenue.

The neighborhood’s Asian-American community has grown at a rapid pace over the past decade, with the majority of those constituents living in two state senate districts — the 17th District, which is made up primarily of Borough Park, and the 20th District, which stretches in the shape of a backhoe through Brownsville and Crown Heights, and includes narrow strips of Park Slope and Sunset Park.

This puts that community at a disadvantage, advocates say.

“The Asian-American community does not have a strong community of interest between these two neighborhoods, largely because of language barriers, and with language barriers comes lack of culturally sensitive social service programs,” said Elizabeth OuYang, coordinator of the APA Voice Redistricting Task Force.

OuYang says in order to ensure adequate representation for Brooklyn’s Asian-American community, it makes the most sense to carve out a district that links Sunset Park with Bensonhurst, Bath Beach, and Gravesend, all of which have substantial Asian-American populations, with the potential to create the first majority Asian-American senate district in Brooklyn.

“The core principles of redistricting, one of them is communities of interest and the other is continuity,” Ouyang told Brooklyn Paper. “The N and D lines link these communities together, so we think there is the possibility to create the first-ever Asian-American senate majority district in Brooklyn, and additionally more assembly districts.”

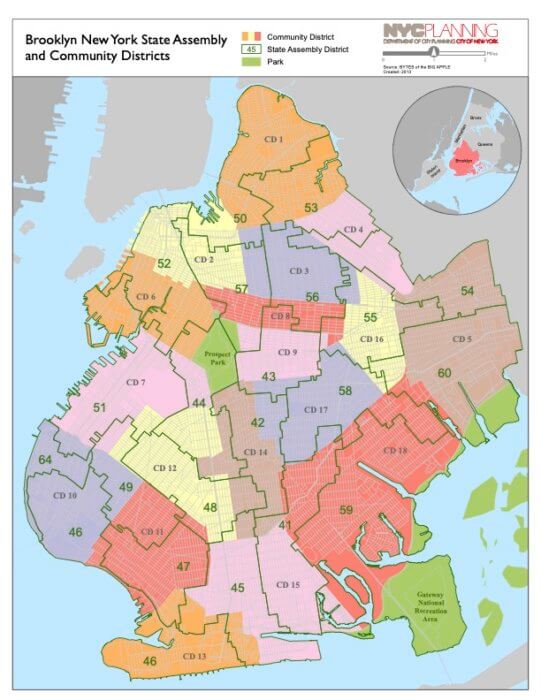

A similar problem persists in Bay Ridge, where the large and growing Arab-American community finds itself concentrated where three assembly districts — the 46th, 49th and 64th — all converge.

“This results in our community being unable to elect candidates who share their experience and who will prioritize their needs,” testified Arab American Association of New York organizer Yafa Dias during the commission’s public hearing on July 29.

With the boundaries set to stay in place for the next 10 years, it’s essential that the new lines reflect the ever-changing communities in Brooklyn, according to advocates.

“In this whole process we want all marginalized groups to be able to have access and equal representation,” OuYang said. “That’s what makes democracy a democracy, full participation — and you can’t have full participation if your communities are divided.”

Here’s how the districts currently break down:

For more on your district, and others, check out Redistricting and You, an interactive map created by the Center for Urban Research at CUNY’s Graduate Center.