The springtime sun is bringing Kings County back to life, drawing Brooklynites out by the thousands to enjoy the borough’s lush parks and sandy beaches.

They’re accompanied — though they don’t always know it — by thousands of species of wildlife doing just the same thing. Spring is migration season, when roving species return home or pass through the city on their way to greener pastures, and for those who call New York City home, it’s also time to start raising little baby animals.

Spotting wildlife in the city — aside from rats and pigeons – can feel unlikely. But if you know where to look, and what to look for, unusual animals are all around.

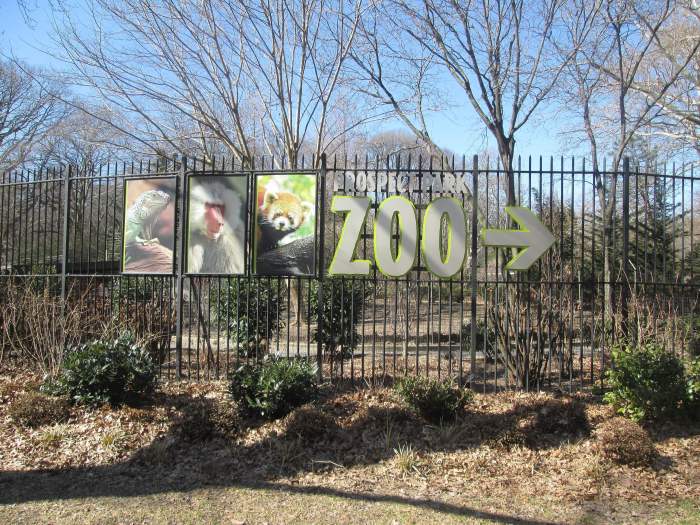

For Chris Altieri, the founder of the NYC Plover Project, appreciating the city’s wildlife started during his daily trips to Prospect Park in the first months of the pandemic.

Altieri, who now helps to educate about and protect some of the city’s most fragile birds, hadn’t given much thought to Brooklyn’s avian visitors.

“It wasn’t until I went out there and I found this community of people who were just so excited about these little birds in particular called warblers,” he said. “These warblers are just like little rays of sunshine, and little candy-colored bursts that just appear in the trees.”

Those sweet-singing, brightly colored warblers stop over in Prospect Park every year on their journey from Central and South America to the northern U.S. They’re joined by tanagers, orioles, and many more birds who need a place to rest and recoup on their thousand-mile trips.

Bird watching surged in popularity during the worst of the pandemic as New Yorkers took solace in the outdoors, watching as migratory birds — not bound by the lockdowns — flitted to and fro.

“As a New Yorker, I became very distant from the fact that we are in a series of ecosystems, and I really thank the pandemic for getting me out there, to open up my eyes and look up,” Altieri said. “Sometimes, birds, though, you have to look down. And that’s shorebirds.”

Piping Plovers ‘day trip’ to Plumb Beach

New York City has 14 miles of beaches — and as they fill up with humans during the summer months, they also fill up with birds.

Of particular import to Altiere is the Piping Plover, a seven-inch long, two-ounce shorebird. The tiny beach-dwellers are endangered in New York and threatened across the U.S. — there are only between 6,000 and 8,000 left in the world.

And about 50 breeding pairs of them (100 birds total) spend their summers in New York City, raising their cotton-ball sized chicks in fairly tough conditions. They nest mostly in Queens, everywhere from Breezy Point to Fort Tilden.

But the plovers spend a fair amount of time Brooklyn — making “day trips” to Plumb Beach especially, Altieri said — and he expected to see some nests in Kings County as soon as this year.

That’s encouraging news for nature-lovers, but it’s worrying, too. The plovers nest right on the beach, and their nests and miniscule babies are particularly vulnerable. Plumb Beach has become sort of an unofficial dog beach, he said, and off-leash dogs pose a huge risk to Piping Plovers, as do large crowds of humans.

To protect the plovers, officials have to temporarily close the portions of the beach where they choose to nest, often to the dismay of beachgoers.

Alteri said he hoped elected officials and everyday New Yorkers alike could learn to love their feathered neighbors, and understand why the beaches must be closed — rather than treating it as a nuisance.

“We just need to look at this through a different lens that’s more positive,” he said. “When people get out there and see these birds, and when they see the chicks, forget about it. It’s melted the most icy hearts, I’ve seen this happen. And they’re just so excited to see these little birds.”

Piping plovers always have four eggs, he said. If one of four survives even a few days, it’s “a miracle,” he said. If they can survive a month, to the point where they can fly, then they’ll probably be able to begin their long migration back to Central America.

“You cannot have a packed open beach and Piping Plovers surviving at the same spot,” he said. “So we have to close down part of the beach, or sometimes an entire beach. It is temporary. It’s like a nanosecond in a human lifetime, but it’s a temporary closure that can actually be the difference of a chick surviving.”

Some birds expand the definition of ‘shore’

Piping plovers are one of dozens of shorebirds who spend their summers in Brooklyn — but some favor a more unlikely setting than the picturesque beaches — the Newtown Creek.

The creek, a federal Superfund sight infamous for its deeply-polluted waters, is nonetheless the go-to spot for Great Blue Herons, Great Egrets, and even rarer species like Yellow-Crowned Night Herons, said Willis Elkins, executive director of the Newtown Creek Alliance.

Balancing atop their long skinny legs, egrets and herons wade through the shallow waters of the creek, searching for crabs, fish, and other prey along the shore. They’re joined by diving birds — double-crested cormorants and kingfishers — who slice through the water on their hunts.

There’s not much wading space, either, Elkins said, and the fish and crabs who live in the Creek are perhaps not ideal foods for any creature. The state Department of Health recommends that humans eat fish caught in the East River only about once a month, and discourages children and pregnant people from eating any at all.

Of course, the egrets and herons can’t read those warnings.

“But regardless of those challenges, they’re here and they come back every summer,” Elkins said. “So it’s really cool to witness that and see them coming back.”

The much-needed Superfund cleanup of the Newtown Creek still hasn’t started, and isn’t expected to begin until 2032. A full federal scrub is what’s really necessary to restore the Creek and its habitats, Elkins said, but there are some shorter-term projects in the works — like the Newtown Creek Natural Resource Damage Assessment Plan, which is open for public comment until May 30.

It focuses on repairing the damage done to natural resources in the Creek, Elkins said, and is likely to include “large investments” to restoring habitats for fish, birds, mollusks, and more.

“We’re hopeful, again, that this will bring some resources to restore some of those essential ecological pieces that are missing from the creek,” he said.

But in the meantime, there’s plenty to see – even though conditions are tough. In the tide pools along the Newtown Creek Nature Walk, where Brooklynites can get really close to the water, there are more small organisms — fish, eels, jellyfish. A group of school kids on a field trip recently spotted what they thought was a dog fish, a species of small shark.

One fish species was particularly exciting to Elkins – menhaden. The roughly foot-long silver fish aren’t particularly appealing to humans, but they are known as one of the most important fish in the sea. Menhaden are a crucial food source for larger fish, shorebirds and some birds of prey — and even whales and seals.

A little fish brought whales and seals back to Brooklyn

The menhaden population is also booming in the New York Bight – a triangle-shaped slice of the Atlantic Ocean between southern New Jersey and the eastern tip of Long Island, including the waters around New York City.

Off the coast of southern Brooklyn, the menhaden have brought back whales, seals, and dolphins.

Gray seal pup sez what up? New York harbor is the cleanest it’s been in over 100 years. This knucklehead is living his best life. @TheWCS @NOAAFisheries pic.twitter.com/uNfSOIFBcB

— Justin Brannan (@JustinBrannan) April 22, 2024

Seals are usually wintertime visitors to New York – as the weather warms up, the seals who spent the colder months snoozing in the city and on Long Island are starting to head north — but some other large marine visitors are getting ready to spend summer break off the southern shores of Brooklyn and Queens.

“Dolphins should be in the bay starting now, when the menhaden come in, and the whales will start coming in now,” said Don Riepe, the former director of the local chapter of the American Littoral Society. “Thirty years ago, we didn’t see seals, we didn’t see dolphins, we didn’t see whales here. They passed through, but now they summer here, because the food resource is here.”

Whale-watching may sound like a vacation activity, but the American Princess whale watching expeditions leave from right here in Sheepshead Bay. Though it’s rare, dolphins have even ventured as far north as Greenpoint.

But, like Altieri, Riepe is particularly excited about the birds. Migration for shorebirds tends to peak in late May, he said, depending on the weather — clouds and rain aren’t great flying conditions, so they often arrive in waves after a few slow and cloudy days.

“Early on, we’re looking forward to seeing the return of the oystercatchers — one of the first shorebirds to return,” he said. “The glossy ibis, a very iconic species. I’m looking forward to the return of the Great Egrets, because one of them, we’ve named it Edgar, comes and visits me everyday. He lands on my dock and he walks into my house.”

Jamaica Bay, sitting sandwiched between Brooklyn and Queens, is a hugely important estuary for marine life, Riepe said — fish, birds, and even creatures like horseshoe crabs find a safe home there.

Life can be hard for wildlife in New York City, but Riepe is encouraged by all of the city, state, and federal agencies working to protect the animals — and the environmental groups doing the same.

The first step to wildlife protection is “to see them,” said Altieri.

“Realize that they are New Yorkers too,” he said. “The next step is to learn a little bit about them … the third step, is maybe [to] become empowered to speak up for them.”

Curious New Yorkers can use the NYC Parks Urban Wildlife Calendar to see which creatures will be popping up in New York City and when; and can learn more about each animal — and report sightings – on the Wildlife NYC website.

“Wildlife sightings tend to get more common as the weather warms and wildlife become more active,” said Richard Simon, director of the parks department’s Wildlife Unit. “Since many species give birth to their young in the spring, this season is a great time for catching a glimpse of baby birds and other young animals. Remember – if you cross paths with wildlife, respect them the same way you would any other New Yorkers, and give them plenty of space.”