A ventilation system to protect students at a Gowanus elementary school from contaminated air has passed its first round of testing, according to state officials, but isn’t set to be fully operational until at least after Christmas.

Officials tested the air at P.S. 372 The Children’s School earlier this year as part of a larger Soil Vapor Intrusion study in the neighborhood surrounding the toxic Gowanus Canal Superfund site.

The results showed the air inside the school’s main building on Carroll Street was safe by state standards.

But in the soil below the school’s annex building on First Street, officials found very high levels of oil-related chemicals including ethylbenzene, trimethylbenzene, and xylenes. Exposure to those chemicals over long periods of time, or at high concentrations, can lead to serious health effects.

The indoor air in the annex basement itself, which houses kindergarten classrooms, was largely found to be safe, though the results appear to show higher-than-average levels of a xylene isomer. While the air in the basement doesn’t pose a significant health risk, according to the state’s Department of Environmental Conservation, the results required action.

The highly-concentrated contaminants in the soil are liable to rise up into the basement itself via soil vapor intrusion, and the state offered to install a free sub-slab depressurisation system to vent the vapors outside before they can reach the basement and the students.

But the system wasn’t done before the first day of school on Sept. 4.

‘We are moving as fast as we can’

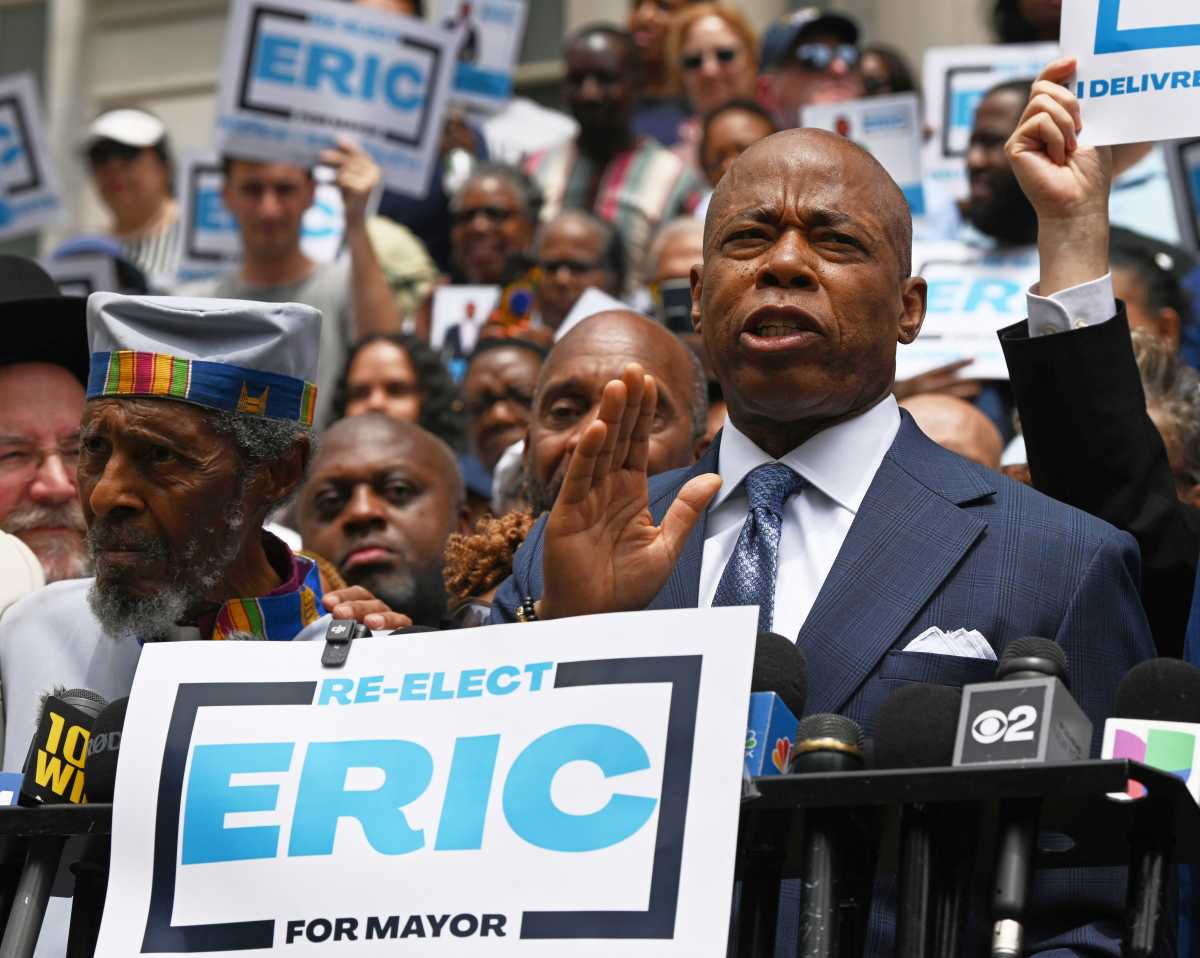

At a Sept. 19 meeting at P.S. 372, DEC project engineer Heidi Dudek said tests for a pilot system are finished and went well.

While testing was underway, officials were also designing the permanent system for the school, Dudek said, and hope to finish the plan by early October. After that they’ll have to meet with the building’s owners — the annex is leased to P.S. 372 by a church next door — and the Department of Education to get the system permitted and installed.

“I am very realistic, I don’t want to give anybody false hopes,” Dudek said. “It does take time. We are moving as fast as we can, I do not anticipate the system will be installed before Christmas, we think it’s going to be early 2025.”

In the meantime, the city’s Department of Education and the state health department have installed new air conditioning units and exhaust fans in the annex to keep the building properly ventilated, according to Gothamist, and added carbon dioxide detectors to the school’s HVAC system. Ventilation is a key short-term fix for soil-vapor intrusion, according to DEC — in a June letter to the pastor of the Carroll Street church that owns the annex, a department health specialist recommended opening windows and adjusting HVAC systems to reduce the levels of contaminants in the indoor air.

State officials also said DEC’s standards for what’s considered unsafe are “conservative.”

“Our levels where we recommend action are not levels where we would expect to see health effects,” said Scarlett Messier-McLaughlin, a public health specialist at the state DOH. “They’re proactive, they’re pretty conservative. So, in this case, in the school, we recommend mitigation, but it’s not something that’s exceeding immediate action levels.”

The source of the contamination in the soil isn’t clear. Officials had initially believed the chemicals were left over from oil tanks that used to be left on the property, but also theorize they are migrating from a Brownfield cleanup site on 4th Avenue. Some of the same chemicals found in the soil at P.S. 372 were found in the soil and groundwater at the Brownfield site, documents show.

Janice Clear, a parent with two children at P.S. 372 — including one who was in kindergarten last school year, when the results came out — isn’t worried.

A structural engineer, Clear said she felt her children were safe after she read the full report.

“I wish they had a little bit more emphasis that no high levels were found in the air; they were all in the soil vapor under the slab,” she said. “That the kids aren’t breathing anything, which is why there’s no reason to take the kids out.”

However, not all parents at P.S. 372 are convinced.

At the start of the school year, members of the school’s PTA met with Joseph Allen, the founder of the Healthy Buildings program at Harvard University to get his opinion, they shared in a Sept. 5 update shared online.

Allen said he wouldn’t pull his children from the school over the results, the update states, but would push for mitigation and monitoring — and was happy with the state’s decision to install a sub-slab system.

But he advocated for installing advanced monitors that would track all volatile organic compounds in the school’s air, and some parents — like Julia Finegan, co-president of the P.S. 372 PTA, urged officials at the Sept. 19 meeting to look into more extensive monitoring at the school.

The PTA is considering purchasing some monitors to keep in classrooms separately, according to a Sept. 23 update.

Limited testing with promising results

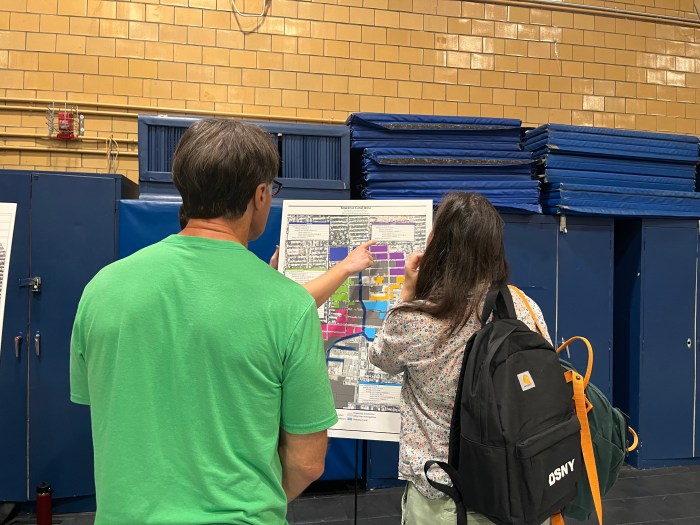

The Sept. 19 meeting wasn’t just about P.S. 372 — it was about soil vapor intrusion test results for hundreds of properties around the Gowanus Canal. Last year, DEC expanded its test range significantly after hazardous volatile organic compounds were found in the air at several Gowanus-area buildings.

The same industrial businesses that defiled the Gowanus Canal in the 19th and 20th centuries left the land around the canal soaked in oil, gas, and other pollutants, and those pollutants can make their way into homes and businesses the same way they did at P.S. 372.

A year ago, the state sent out requests to test 610 properties in a roughly .3-square-mile area around the canal. But only 128 property owners agreed to the testing — most didn’t reply at all, and a few denied the testing outright.

Since then, testing has been finished at 113 properties, according to DEC, 15 of which needed mitigation of some kind. The state doesn’t release the test results publicly by address, but anonymized results show a number of properties required mitigation for tetrachloroethylene (PCE) and trichloroethylene (TCE.)

PCE and TCE are some of the most broadly concerning chemicals in and around the Superfund site. Used in dry-cleaning and chemical solvents, respectively, both compounds are likely carcinogens and can cause a host of other health issues.

While the results were concerning to locals, Dudek said they are so far better than expected.

“The food news is we didn’t see nearly as much contamination as one might expect from a 100-plus-year-old industrial area,” she said. “It’s not everywhere, I guess would be the easiest way to put it. It seems to be small, isolated areas.”

However, testing is still limited. Only 20% of the properties contacted about testing agreed, and while the state will try again this fall — Messier-McLaughlin said DOH plans to reach out to about 1,400 properties — they can only test where owners have allowed them to.

Landlords are required to share test results with their tenants, but they’re not required to agree to the testing. At the Sept. 19 meeting, officials urged Gowanus tenants in the testing area to contact their landlords and talk with them directly if they want their homes tested.

Several Gowanusians were left frustrated by the end of the meeting. Martin Bisi, a local resident and member of the activist group Voice of Gowanus, said officials’ insistence that test results were not much to worry about felt like they were saying “I told you so.”

Bisi said results showing how widespread the contamination in Gowanus is were “jaw-dropping,” and supported VoG’s demands for more testing and additional surveys, especially with thousands more buildings expected to pop up in the neighborhood in coming years thanks to the Gowanus rezoning.

Stephen Sollins, who lives just outside Gowanus but works in a building beside the canal, was also unsatisfied. His workplace was not on the list for testing, despite its proximity to the canal and some of the most polluted sites in Gowanus — including Public Place.

“I think they said that if we could get the landlord to agree, they would come and test the building, but it’s kind of interesting that it seems to not even be of concern to anybody,” he said. “Maybe because the zoning hasn’t changed right there, it’s still industrial. But a lot of people work there.”