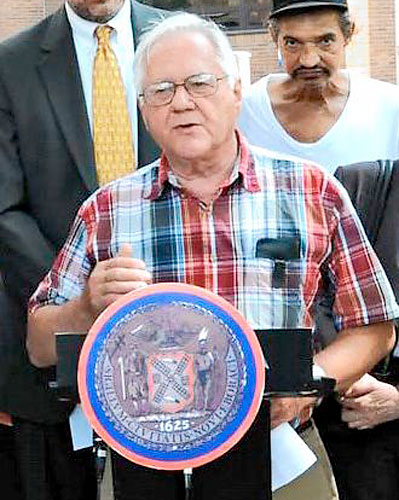

Murray Adams, the indefatigable lion of Cobble Hill who spent nearly half a century advocating for neighborhood causes, died Tuesday at Long Island College Hospital from complications from a stroke. He was 79 years old.

The son of a college president, Adams was a lawyer by trade who in the 1950s, helped co-found the Cobble Hill Association, a civic group. Later in life, he battled to keep the fiscally challenged Long Island College Hospital firmly rooted in the neighborhood, helping to organize and conceive its eventual merger with SUNY Downstate.

“Today is a sad day for Cobble Hill,” said Roy Sloane, president of the Cobble Hill Association.

“He played an integral part in shaping the neighborhood from one threatened by urban renewal and Atlantic Avenue becoming a state highway to one of Brooklyn’s premier family neighborhoods. He did this through his intelligence, his charm and his tireless dedication to improving our institutions and our local political representation.”

Charles Murray Adams was born in Ithaca, and moved to Long Island when his father, John C. Adams, was named president of Hofstra College. He returned to the town of his birth to attend Cornell University, then served a stint in the Army, and later attended Harvard Law School, according to his son, Kenneth Adams, himself a Brooklyn legend who is now the head of the Empire State Development Corporation.

Adams moved to Brooklyn in 1961 — spent two years in Brooklyn Heights before moving to Cobble Hill — and worked the majority of his career practicing real estate and corporate law for the New York-firm Reavis & McGrath.

But friends said he was a lawyer who never behaved like one.

“He was very down to earth,” said Jerry Armer, a civic activist. With Adams at the helm, the Cobble Hill Association’s executive board would convene inside his Amity Street house.

“He always made you feel at home,” Armer recalled.

He also served as a board member and general counsel to Long Island College Hospital, where interim president Dominick Stanzione, described him as a “dedicated friend and supporter.”

He was also stridently opposed to housing inside Brooklyn Bridge Park, serving as an advisor on a failed lawsuit aimed to prevent its arrival, which would set a disastrous precedent.

For Adams, community affairs helped feed a desire to fix things — both real and esoteric.

“He liked solving problems,” his son said. He was very mechanically inclined and was a very skilled carpenter.”

In his spare time, Adams would build TV sets and furniture for the family, his son recalled. A few months ago, he installed an oven in the home.

“He always believed he could fix things,” Ken Adams said.

Adams is survived by his wife, Lucy; sons, Jonathan, Kenneth, and Neil; and five grandchildren.

At press time, funeral arrangements were not finalized.