“Trace/s,” the Brooklyn Public Library’s newest exhibit, was unveiled last week in Downtown Brooklyn, connecting the legacy of slavery in the borough with its living descendants.

“Slavery didn’t just happen in Brooklyn; it changed Brooklyn,” states one of the plaques on the exhibit walls. “Enslaved people in Brooklyn transformed the terrain of Kings County from an ecosystem of Indigenous land stewardship to a network of thriving plantation farms, and later into a budding urban center.”

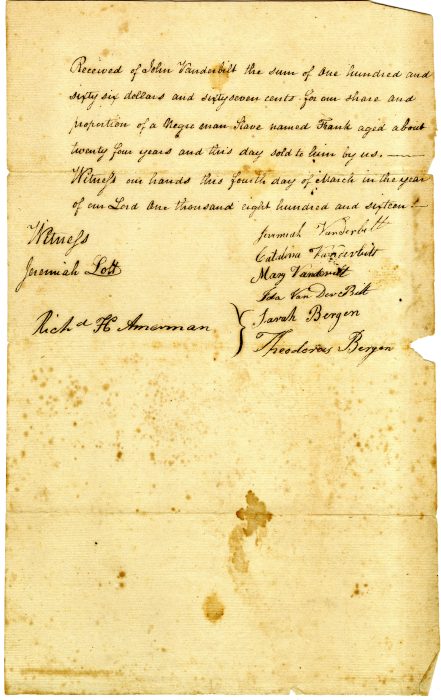

The exhibition displays items such as bills of sale for enslaved people, journal entries, possession inventories, and newspaper clippings detailing the extensive practice of slavery in the borough.

“Trace/s” also prominently features two striking oil portraits hanging side by side. One depicts John A. Lott, a slave owner in Flatbush, while the other shows Mildred Jones, the great-great-granddaughter of an enslaved person owned by the Lott family.

Lott is shown proudly standing in front of law books, presenting himself as a wealthy and educated figure in Brooklyn society.

Jones posed for the portrait in 2024 for the exhibit. Framed by cool tones of blue, the painting captures her vibrancy. The portrait depicts Jones seated with a cowbell in her hands. The bell has been passed down through generations since her family’s enslavement.

Exhibition organizers commissioned the oil painting to cement Jones and her family’s lineage into the record of Brooklyn’s history.

Jones, now in her 80s, graciously posed in front of her portrait on the exhibit’s opening night.

“ I’m sensing the whole importance of us doing our genealogy,” she told Brooklyn Paper. “It’s not so much about who we are as individuals, but it tells a bigger story, and we need that bigger story to be told.”

Such stories, Jones added, are more important than ever before.

“We need to keep telling it because this is the time they are trying to erase us, and we don’t need to be erased,” she said. “We’re not going to let that happen, so we’re going to tell our stories.”

With support from genealogical research conducted by Jones’s family members, the Afro-American History and Genealogical Society (AAHGS), and the Center for Brooklyn History, the Jones family traced their lineage to an individual enslaved at the large Lott plantation in Flatbush.

Samuel Anderson, the great-great-grandfather of Mildred Jones, was born into slavery under the Lott family. After the abolition of slavery in New York in 1827, Anderson became a free man.

Before emancipation, 60% of white households in Kings County were reported as owning enslaved people, according to census data gathered by researchers at the Brooklyn Public Library.

Stacey G. Bell, president of the AAHGS New York Chapter, discovered her own connection to the Lott plantation while assisting the Jones family with their research. Bell found that she resides on land that was once part of the Lott family’s plantation on Cortelyou Road in Flatbush.

“Brooklyn was such a national center of slavery in its heyday here,” said Dominique Jean-Louis, chief historian at the Brooklyn Public Library. “And I don’t think people really realize that Brooklyn is, on the one hand, a place where slavery took place at all. And secondly, how prevalent it was.”

Muriel D. Roberts, also known as Dee Dee, 71, contributed to the exhibition by sharing a document that showed her great-great-grandmother, Rachel Barnett Peterson, who was of Native American and African descent, had a direct connection to Brooklyn’s history of slavery.

“I never knew there was slavery in New York,” she told Brooklyn Paper. “I found out slavery was abolished in 1827, and the paper was from 1825. So it gave her freedom — that she was a free person. You had to prove that.”

Chief Historian Jean-Louis relied on small clues like the “Indian paper” passed down through Robert’s family to help create “Trace/s.”

On opening night, Jean-Louis shared the significance of the exhibit’s title.

“Trace is a word of action, a verb. It refers to following a line, a trail of evidence. It’s the action that family history researchers take,” she said. “Tracing is also, quite literally, the act of sketching out early outlines with pen and with paper or with oil on a canvas.”

“ A trace is also a piece of equipment that connects livestock to the person who is managing their labor — a harness, a symbol of bondage,” she went on. “This exhibition addresses the fact that Brooklyn was the site of human enslavement for more than 150 years.”

“Trace/s” is on display at the Center for Brooklyn History, 128 Pierrepont St. in Brooklyn Heights, now through Aug. 30.