The plan for a Southern Brooklyn storm break is broke.

Federal officials from the Army Corps of Engineers revealed the ugly truth for its multi-billion-dollar coastal storm barrier project, which includes a massive flood gate, to make Southern Brooklyn more resilient in the five-year aftermath of Hurricane Sandy — there is no money.

But the news was just the latest let down in the years that have passed since the devastating storm, and it dried up the last bit of hope that the coastal neighborhoods will ever get protection from the ocean, said a Southern Brooklyn environmental activist during a resiliency town hall at the Coney Island YMCA on June 1.

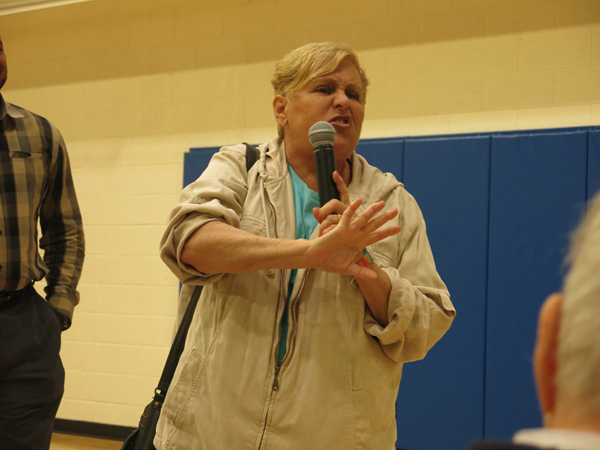

“I call that flood gate the ‘when-pigs-will-fly flood gate’ because pigs will grow wings and fly before that flood gate is built,” said Ida Sanoff, who lives in Brighton Beach. “Hurricane Sandy flooded all of us. It’s been five years since, what do we have? Nothing. How many meetings have you been to, five meetings, 10 meetings, 20 meetings? Here is the bottom line, we need something done now.”

Of the $5 billion Congress signed off on in 2013 for all Hurricane Sandy-related resiliency projects from Virginia up to Maine, only about $1 billion is left, Army Corps project manager Daniel Falt told attendees of the multi-agency meeting.

And on the heels of President Trump’s decision to pull out of the Paris Climate Agreement — a 195-country pledge to curb greenhouse emissions and slow the effects of climate change — the imperative to fight for the nearly $4-billion project, which would minimize the risk of rising sea levels, is even more critical, said Councilman Mark Treyger (D–Coney Island).

“Earlier today, the president of this country detached our nation from an agreement that really matters a lot to us, should matter a lot to us — an agreement that commits this country to reduce our carbon footprint in the world, to reduce or to try to slow down the rate of climate change,” said Treyger, who chairs the Council’s committee on recovery and resiliency. “The Army Corps I think is very much aware that there’s a shortage of funding for that project. We need to make our case and we need to make it very clear that we deserve the same level of protection as anyone else in New York City.”

Picking up the pieces and rebuilding right after the 2012 storm was crucial, but now it’s time to prepare for the future — and it takes believing in the science of climate change to do so, said Rep. Hakeem Jeffries (D–Coney Island).

“The transition we need to make is where we can eventually get to a point where we can strengthen the resiliency of all of the neighborhoods along the Coney Island peninsula,” said Jeffries. “Particularly in recognition of the fact that the climate, despite what the 45th President of the United States may think, the climate is changing, global warming is real, sea level rise is occurring. And we know that because we experienced it on Oct. 29 when superstorm Sandy hit.”

The Army Corps study initially only included Queens, but Jeffries and Sen. Chuck Schumer (D–Park Slope) fought hard to get Brooklyn in the plans, and now the proposed $3.8-billion project includes the massive hurricane barrier extending from Queens to Floyd Bennett Field in Marine Park, concrete floodwalls, reconstructed seawalls, sand dunes, and jetties. Just the hurricane barrier for Floyd Bennett Field alone would cost a whopping $1.5 billion, said Falt.

Back in October, there was still about $3.5 billion left, but now that number has shrunk by more than half, and there are still a number of other projects ahead of this one in the pipeline that may dry it all up before the Corps plans to break ground in Coney Island in 2019, said Falt.

Congress will have to go back to square one and allocate more cash, said Falt.

“What we have for this system is about $4-billion of proposals, so you can see that’s a significant problem we face,” he said. “But if we could get this authorized we would just simply need to get additional appropriations from Congress.”

But to hopefully see some action soon, the Corps is looking at what smaller parts of the project — such as sand dunes and planting more grass — can be done quickly from the money that’s left before it’s gone, he said.

“We are going to use that money we have to build some of the elements of the project, we’re not going build half a gate — interim protection, some sort of dune, grass planting, that’s an easy solution,” said Falt. “And shame on us for not doing it already, we are trying to get something done as soon as we can.”

Jeffries attributed the snail’s pace of the project to the change of hands in the White House, but promised to fight to move it along.

“We can try to push for this to be done as quickly as possible, and I understand your frustration and everyone’s frustration with the long-term process,” he said. “But we are talking multiple administrations. We did have President Barack Obama, now we have President Donald Trump, it’s a change in administration, that’s challenging — multiple billions of dollars at stake and multiple jurisdictions, but we are trying to work through it as quickly as possible.”

One glimmer of hope might be President Trump’s promised $1 trillion infrastructure plan, some of which could be steered toward to Southern Brooklyn’s resiliency, according to the congressman.

“To the extent that Congress comes together to pass a major transportation infrastructure initiative for our nation, there will be opportunity to get these projects funded,” he said in an e-mailed statement. “However, absent any major infrastructure initiative the likelihood of securing additional funding is challenging.”