Call it organized grime.

Mayor DeBlasio wants to take the city’s commercial waste hauling system back to the days when the mob ruled, by once again creating small territories and only allowing a single company to operate in each one — a move it hopes will curb the trucks and fumes choking the streets of industrial neighborhoods like Greenpoint and Williamsburg, but which critics say is throwing small, local businesses on the trash heap, as they will never be able to compete with Big Garbage for the gigs.

“If the city goes through with commercial franchising, this business is out of business,” says Cobble Hill resident and third generation Brooklyn trash hauler Stephen Leone, who employs 24 people and operates five trucks at his Clinton Hill company Industrial Carting. “I fear that we will not be qualified to bid, based on size and scope.”

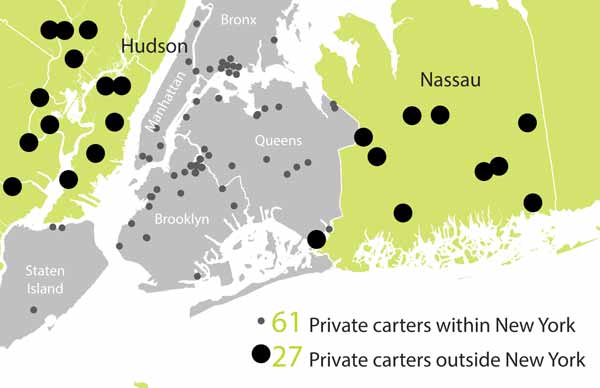

Right now, any hauler can work in any neighborhood, so multiple trucks are rolling down the same streets to collect refuse from neighboring businesses.

By carving out fiefdoms of filth around the five boroughs — this time with the city calling the shots, rather than “legitimate businessmen” — the city claims it can cut truck fumes in half, dropping carbon monoxide emissions alone from 88 tons to between 18 and 36 tons, and reduce traffic in every neighborhood, especially in blue-collar areas where most private waste transfer stations are clustered.

Residents and pols in Brooklyn’s northern nabes have long complained that they are saddled with far too many of the detritus depots, and say they’re thrilled the city is finally cleaning up its act.

“It’s great news,” said Luis Velasquez, who has lived near Porter Avenue and Grattan Street since he was 5 years old and is a member of activist group Clean up North Brooklyn. “For less traffic, less pollution — not only for our community, but for the entire city.”

There are several transfer stations near Velasquez’s home and he says it’s common to see dozens of trash trucks idling in the nearby streets for 20 minutes waiting to unload, and that many drivers pay no attention to stop signs, cyclists, and kids walking around.

He and other proponents argue the city will also be able to crack down on safety and working conditions better if it is vetting the vendors itself.

But Leone thinks the city is putting the trash cart before the horse. The current regulations governing the industry are almost entirely focused on keeping the mafia out, and if the city suddenly wants to reduce truck traffic, it should start by modifying its rules instead of junking the entire system, he says.

“The industry is being judged on a criteria that no one ever told us was important!” he said. “The outcomes you see in the marketplace are a direct product of the rules — adjust the rules and you’ll see different outcomes.”

The city says it will ensure smaller operations like Leone’s have a place in the new order by creating zones just for them. But he argues that will still leave all the mom and pop vendors fighting for literal scraps, and some will inevitably lose out.

A Department of Sanitation rep claimed the agency can’t speculate on whether jobs will disappear because it hasn’t figured out exactly how its new scheme will work, but nevertheless said a study it funded found the free-market system can never be as eco-friendly as its big-government solution.

“Even factoring in the many customer service preferences that make routes less efficient … the reduction in truck miles travelled and overlap are reduced in a zone system far beyond what could be done in the current system,” said spokeswoman Belinda Mager.

The city will now spend two years working out the particulars and convincing Council members to vote for it, though it doesn’t plan on implementing the changes for another six years, according to Mager.