Brooklynites of color face myriad forms of racism wrought by structural forces in city law, according to a new report by the city’s Racial Justice Commission.

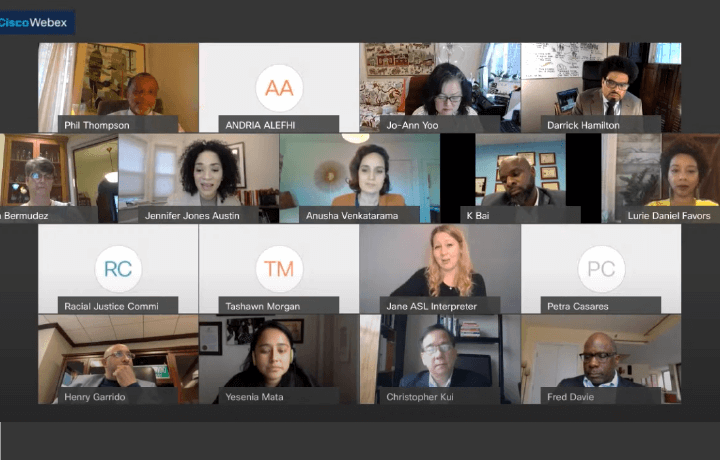

The report is the first by the Commission, which was empaneled by Mayor Bill de Blasio earlier this year to identify areas of city law perpetuating racism and recommend charter revisions to correct them.

The commission’s goal is not to recommend specific, granular policies and initiatives, but to create broad, “bold” charter revisions that root out structural racism in the city’s foundational document in a wide range of areas, and to ensure accountability for city government to uphold those principles.

The report, based on testimony from over 100 New Yorkers at nine in-person public input sessions plus over 1,000 online comments, identifies six broad areas of inequity, where racism is baked into city law and society subjugates New Yorkers of color. Those areas include: access to quality public services, distribution of resources across neighborhoods, professional advancement and wealth-building, marginalization and over-criminalization, representation in decision-making, and enforcement and accountability for government and other entities.

At the August hearing in Brooklyn, for instance, several speakers noted that communities of color suffer from a paucity of mental health resources (and when they’re available, they’re often inaccessible, possibly in a language they don’t speak), and that New Yorkers of color, particularly Black New Yorkers, are less likely to receive adequate mental health treatment as a result, a fact that has wide-reaching implications.

Public input highlighted in the report included the notion that wealthier neighborhoods should bear a more equitable burden of infrastructure that can negatively impact health and wellbeing, such as those that emit substantial amounts of pollution, while many speakers highlighted the well-documented disparities in how police treat people of color versus whites.

“Speakers pointed out that the safest communities do not have the most police,” the report reads. “They have the most resources.”

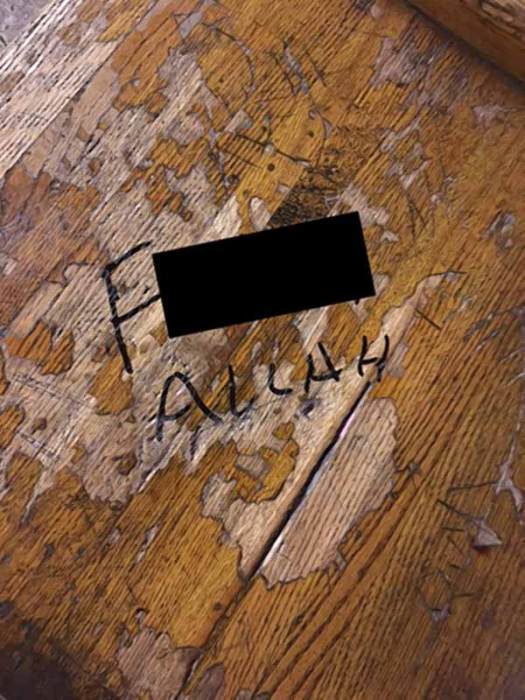

Over-criminalization, the commission says, has pervaded many aspects of everyday life for New Yorkers of color; the report notes that students testified that having police in schools did not make them feel safer, and that students of color faced disproportionately harsh discipline.

The existing economic and social order is designed to prevent social mobility and perpetuate generational hardship: an example the report gives is low-income workers having to pay for their own job trainings and certifications, while minority-and-women-owned businesses and community organizations are at a disadvantage in the procurement process against well-connected firms with lots of money, and the most vulnerable workers in society lack many protections afforded to others by labor law.

“We must acknowledge how our systems of work and wealth continue to prevent many New Yorkers from offering their strengths and talents or from being fully recognized,” the report reads.

The dispatch precedes a final report expected in December where it will make its final charter revision recommendations, which will be voted on by New Yorkers at the ballot box in November 2022.