The city’s Racial Justice Commission met Wednesday for the second time, and for the first time in Brooklyn, allowing borough residents the chance to testify about the ways city government can change its laws to foster greater racial equity.

The meeting was the second of five public input meetings the commission is holding, one in each borough. The first meeting took place on Staten Island last week. The commissioners will head to Queens Thursday night for the third meeting.

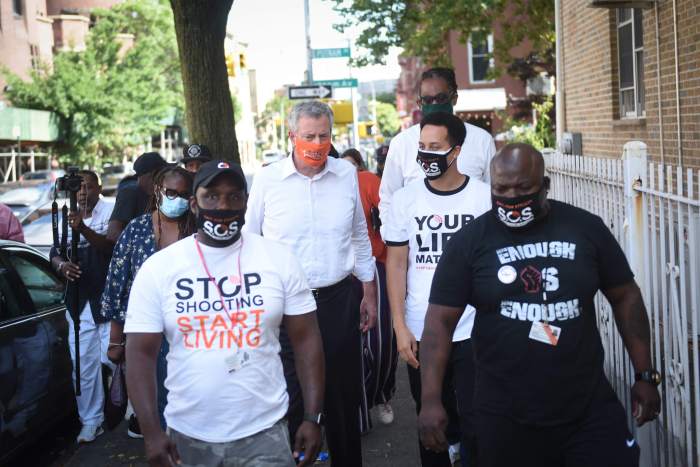

The commission, created by Mayor Bill de Blasio in March, is tasked with identifying areas where structural racism is baked into the city’s laws and institutions, and revising those foundations to uproot racism from city governance. The commission is empowered to make recommendations to revise the City Charter, which would go before voters in the November 2022 election.

“The Racial Justice Commission is charged with laying the groundwork for a racially equitable city where race is not a determinant of economic, political, social, or psychological outcomes,” said Jennifer Jones Austin, CEO of the Federation of Protestant Welfare Agencies and the Commission’s chair, in her opening remarks.

Commission members distinguished the Racial Justice Commission from past charter revision commissions, however, by noting that this one is focusing much more heavily on public input, with commissioners explicitly tasked with listening to community members air their grievances.

“We’re just leaning in, we’re trying to listen,” Jones Austin said in an interview prior to the hearing. “We’re a commission that doesn’t have any foregone conclusions, we are here to simply listen.”

Wednesday’s hearing took place at the Bethany Baptist Church in Bedford-Stuyvesant, a location which Jones Austin noted had special significance in the history of the movement for racial justice as the gathering space in the 1960s for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference’s “Operation Breadbasket,” which organized to improve the economic conditions of Black people across the country, and especially in unequal northern cities like New York while much of the public’s focus was on de jure segregation in the south. Operation Breadbasket’s leaders met every week in the church’s basement, which is where the Racial Justice Commission met Wednesday evening.

At the hearing, 10 Brooklynites testified, including two elected officials, Assemblymember Stefani Zinerman and City Councilmember and Democratic Comptroller nominee Brad Lander, and one (most likely) incoming elected official, Mercedes Narcisse, who won the Democratic primary for City Council District 46. Others included representatives of issue campaigns, along with everyday Brooklynites.

Testimony centered on issues such as education, public safety, policing, administrative staffing, housing, gentrification, and others, but the most prominently discussed issue, one brought up by multiple people, was that of mental health inequity. New Yorkers of color, and particularly Black New Yorkers, are far less likely to receive mental health services and treatment, owing to forces such as stigma, lack of culturally competent care, and a lack of resources in communities of color. The problem has become more pronounced during the pandemic, testifiers said, as New Yorkers of color were highly disproportionately impacted by the virus, which along with preventative measures led to an increase in anxiety, isolation, and burnout.

Pastor Cheryl Anthony, the reverend at Judah International Christian Center in Crown Heights and a Bedford-Stuyvasent resident for 70 years, said that in the absence of professional mental health care, much of the burden is placed on faith leaders such as herself.

“We know in our community, that is the bedrock,” Anthony said. “And in providing services to members in congregations…we have not been adequately trained.”

“My colleagues are despondent right now,” she continued. “They do not have the resources nor the information in order to provide support for their constituents or the community. Having to have a place that they feel safe and secure in order to be able to express the feelings they are experiencing, whether it’s anxiety, burnout, a number of things.”

Narcisse also focused her testimony on mental health, specifically noting that existing mental health infrastructure, public and private, is not culturally competent and is often in a different language from the one spoken at home.

“What we need in our community is to understand the culture. And having whatever literature that we have, to have it in a language that the family can understand. And take it to where people are functioning.”

Jones Austin said in an interview after the event that she was surprised mental health inequity was so heavily discussed, but not shocked given the well-known disparities that exist.

“Hearing so many people talk about mental health was surprising, but appropriate. While surprising, very much on point. Some of the underlying challenges that persist, and the lack of recognition of the mental health and the trauma challenges that keep people of color, and people who are lower-income from getting ahead, and the importance of paying attention to that.”

Another issue brought up at the hearing was that of replacing the existing Civilian Complaint Review Board, the city entity which conducts oversight of the NYPD and recommends discipline for police misconduct, with an elected board with the ability to mete out discipline rather than make recommendations. Attorney John Teufel argued that the CCRB should be replaced with an Elected Civilian Review Board (ECRB), which would allow the Board to be more independent and to better hold police misconduct to account, as opposed to the current structure where the NYPD commissioner has final say, and often overturns CCRB decisions.

Teufel pointed specifically to City Council legislation, the Community Power Act, which would implement the reforms, but that some portions of the bill would require changes to the Charter, most notably Section 18a, which lays out the stipulations and powers of the CCRB.

“Daniel Pantaleo remained a cop for five years after murdering Eric Garner,” Teufel said. “This is largely because of chapter 18a.”

CCRB reform was on the ballot after the 2019 Charter Revision Commission, but many advocates argued it did not go nearly far enough.

Other aspects of city governance included augmenting the city’s land use process, as argued by Lander, who said the system as currently constituted was systemically racist.

“We know for a fact that the policies we’ve had for generations have been systemically racist,” Lander said. They’ve segregated the city for generations.”

He noted that “racial impact studies” should be in the charter as part of the land use process; the City Council recently passed a bill to include these studies in the process, but Lander said putting it in the charter would make them more secure as part of it. He also said that the Comptroller’s office, which he is almost certainly about to take control of, should be required to perform “racial equity audits” of city agencies and programs.

After borough hearings are complete, the commissioners will begin researching the noted issues more closely in preparation of proposing charter amendments, Jones Austin said.

“We are hearing the issues that are being raised, and then doing the research into them,” Jones Austin said after the hearing. “Find out what are the root causes of these issues.”