On a rainy March afternoon, the tenants of 135 Kent Ave. in Williamsburg set up a tarp and a table outside their small apartment building. With baked goods and fresh chai, they were thanking their neighbors for their support and celebrating a victory.

The state’s Department of Environmental Conservation had just barred their landlord from attempting to renovate and remediate the ground floor of their building — which sits on a contaminated Brownfield site – while the tenants are still living there.

“That was a big relief for us, that the DEC is putting a block on this, and we feel protected by that,” said Christian Anwander, who has lived in the building with his wife, Mitra Farahmand, since 2012.

Though the plan would have cleaned the contamination off the site, Answander and his neighbors didn’t trust their landlords — Michael and Jay Weitzman of DoubleU Development — to keep them safe during construction.

They worried that digging below the protective sub-slab barrier under the building could have stirred up the carcinogenic chemicals in the soil below. Closely supervised by DEC, the developers said they would carefully contain any vapor, dust and debris to the ground floor.

But tenants said in the two years they have lived under DoubleU management, they have dealt with myriad of health and safety issues, mostly related to construction. If they struggled with even run-of-the-mill construction, they asked DEC, could they handle the Brownfield remediation?

The recent history of 135 Kent Ave.

Many tenants at 135 Kent Ave. have lived there for years. Sacha Dunn moved in in 2003. When she first toured the building, a converted factory, the apartments weren’t even done being built, she said.

Jake Kaplan moved in in 2008, followed by Chris Niemczyk in 2011 and Anwander and Farahmand in 2012.

In 2013, a decade after the first tenants moved in, they got an unwelcome surprise when the DEC discovered hazardous chemicals in the ground at the construction site next door — then that some of those chemicals were leaching out of the soil below 135 Kent Ave., according to DEC documents.

That led to the realization that their building, which for decades had been used to store dry cleaning chemicals, had been converted illegally, and the land beneath their homes was heavily contaminated.

Tests revealed dangerously high levels of chemicals including tetrachloroethylene (PCE,) trichloroethylene (TCE,) and vinyl chloride in the soil and groundwater on the lot, according to DEC documents.

Further testing showed that PCE — which is known to cause short-term health issues and long-term diseases like kidney and liver cancer — had leached upward into the air inside the building in a process called soil vapor intrusion.

Even on the second floor, where the apartments are located, levels of PCE in the air were far above what the DEC considers safe.

The site entered the Brownfield Cleanup Program, and the state installed a protective sub-slab barrier to prevent more toxins from entering the building. Now protected by the city’s Loft Law, the tenants — though unsettled — felt more comfortable.

“We were lucky that they found out about it because we were being poisoned unknowingly,” Kaplan said. “And they got it fixed and everything was great.”

A decade later, DoubleU called a meeting with tenants, representatives from the DEC and Department of Health, and local politicians to share their plans for the ground floor. According to the presentation they showed that night, which was shared with Brooklyn Paper, DoubleU expected the DEC to approve their plans by July, after a public comment period, and wanted to start construction by August.

Immediately, tenants fought back.

Tenants fight construction plan

Before DoubleU bought the building in 2021, tenants said they were regularly in touch with the former managers, and had issues attended to quickly. But after the sale, they had less and less direct contact with the new owners. Issues like leaking ceilings and deteriorating wood from the water damage went unsolved.

The retail stores that had occupied the ground floor slowly moved out. In 2021, Dunn said, the landlords disturbed the protective sub-slab, potentially exposing tenants to the chemicals contained beneath it.

In an email sent to tenants last month, DEC officials confirmed that the slab was disturbed for an emergency wastewater line repair — without approval or oversight from DEC or DOH — and that the department issued a violation to the owners later that year. The email noted that the slab was repaired as soon as the work was done, and that air filtration units were installed near the disturbed slab.

One evening in late 2022, Nienczyk walked into his apartment and discovered it was filled with a noxious chemical odor. Worried there was a gas leak, he called 911 — who, he said, confirmed there was no gas.

Dunn realized the ground floor had just been coated with paint intended for outdoor use only, and that the fumes were rising through the floor into their apartments. Several tenants had to stay elsewhere until they dissipated, Dunn and Nienczyk said.

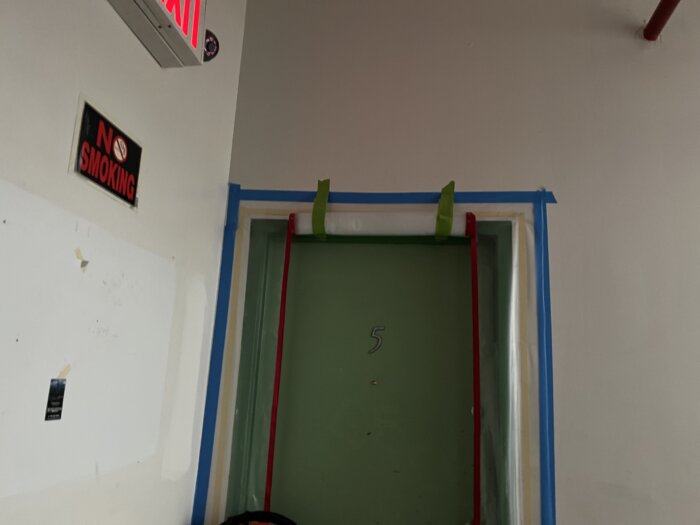

Then, last fall, the landlords started doing construction on the ground floor. As they knocked down walls, they sent up clouds of debris — which tenants later discovered included lead dust.

“There was lead dust all over the building,” Anwander said. “We have three young children living in here, two older kids. We were walking through clouds of dust in the hallways.”

Blood tests later found that Kaplan’s two-year-old daughter and Anwander and Farahmand’s three-year-old daughter had elevated levels of lead in their blood.

“Luckily it’s not any amount that would brain damage the kids,” Anwander said. “How should we trust these people with any other construction going forward?”

Dunn said the summer 2023 meeting where DoubleU shared their plans left she and her neighbors feeling frustrated and unheard. They got in touch with local elected officials, including Council Member Lincoln Restler, who attended the meeting.

Restler advised them to work out what would need to happen to make them feel comfortable with the proposed construction, which was reassuring, she said. They got in touch with lawyers and began negotiating with the landlords.

A few months after the meeting, the landlords offered to help tenants relocate for the duration of the work.

“They wanted to give us $2,600 a month to relocate our families and suggested we might want to sleep on a friend’s sofa,” Dunn said.

The offer wasn’t enough to cover temporary housing for Dunn and her sons, she said. She and her neighbors also worried that even if they came to an agreement to temporarily leave the building, something might happen that would prevent them from coming home.

“Your right of return is only as good as your pockets are deep enough to fight them legally,” she said. “I can’t just leave. It just made no sense, I would rather stay here, but I can’t stay here and poison my kids anymore.”

In February, worried that DEC’s approval of the landlord’s plans was imminent, the tenants launched an online petition titled “Support the residents of 135 KENT AVE in their fight to protect their health and homes.”

They asked their neighbors to support them in urging DEC and the city’s Department of Buildings and New York City Loft Board to reject DoubleU’s plans, and shared plans for a public protest outside their building on March 2.

But then, on Feb. 23, the DEC made their final decision.

DEC issues their decision

The agency technically approved the plan — with the stipulation work can only go forward if there are no tenants living in the building.

“This condition would help prevent any exposure to contamination from ground-intrusive work to implement the cleanup,” a DEC rep told Brooklyn Paper. “If conditions are met, the work would take place under strict DEC oversight in accordance with the approved plan that includes a community air monitoring to prevent any off-site migration.”

That meant that — at least in the short term — no construction could happen at 135 Kent Ave.

Relieved, the tenants called off the protest — but still opted to set up their table outside the building on March 2 to thank their supporters.

“It just sort of resets the conversation to be a little fairer,” Dunn said of the decision.

The tenants don’t know how DoubleU — which did not respond to requests for comment — will respond to the decision, but hope they will accept that things will have to stay as they are for now. If the landlords do try again, they feet confident knowing they had built relationships with each other and had already secured one good outcome.

“It was very empowering actually to witness that people were listening to us and taking us seriously,” Farahmand said. “We didn’t know if maybe no one cares.”

Restler, who represents some of the most contaminated neighborhoods in New York City, said he appreciated that DEC had worked patiently and closely with the community to make their final decision.

“It is appropriate that the landlord be able to advance either an interim remedial solution or, potentially, a comprehensive remediation of the site, only after reaching terms with the tenants,” he said.

Brooklyn alone is home to roughly 134 Brownfield and state Superfund sites, including the former NuHart Plastics factory in Greenpoint and dozens of sites around the Gowanus Canal, where state and city agencies are hard at work remediating parcels of land to be developed as part of the Gowanus rezoning.

It’s fairly unusual, in Restler’s experience, for a remedy to be performed on a site that houses a finished and occupied building, he said. Usually, that work is done on a vacant lot.

He hoped that DEC’s decision at 135 Kent Ave. would “ensure the safety of the tenants while the cleanup is happening and will hopefully lead to a long-term cleanup that is as comprehensive as possible.”