Cleanup is moving along at the former NuHart Plastic Manufacturing plant in Greenpoint as a developer prepares to build two mixed-use buildings on the heavily contaminated lot.

The western half of the 1-acre site, located between Dupont, Franklin, and Clay streets, was named to the state Superfund list in 2010 after potentially-hazardous chemicals were discovered in the soil, left over from nearly 50 years of plastic and vinyl production at the NuHart factory, which closed in 2004. Last year, Madison Realty Capital started taking ownership of the plot after its old owner filed for bankruptcy protection. Taking over NuHart West also means taking responsibility for the Superfund activities deemed necessary by the state, and Madison also applied for and began a Brownfield cleanup of NuHart East.

When all is said and done, and NuHart East and West are deemed clean and safe, Madison is planning to construct two new buildings with about 470 apartments, below-grade parking, and ground-floor retail space, said Zach Kadden, the company’s director of development, at a meeting held by North Brooklyn Neighbors on March 7. A number of units will be set aside as “affordable” under the tax law 421-a and the Affordable New York program.

What’s in the dirt?

Greenpoint’s soil is a smorgasbord of old industrial solvents and chemicals from decades of manufacturing. According to the DEC, the chemicals of most concern at the NuHart site are phthalates, which are used to make vinyl and plastic products more flexible, and a volatile organic compound called trichloroethylene or TCE, a man-made solvent. TCE is a known carcinogen, and while the health effects of phthalates are not definitively known, the federal Environmental Protection Agency is primarily concerned about the possibility that some are “endocrine disruptors,” which negatively affect hormone systems. Endocrine disruptors are of particular concern to pregnant people and young children.

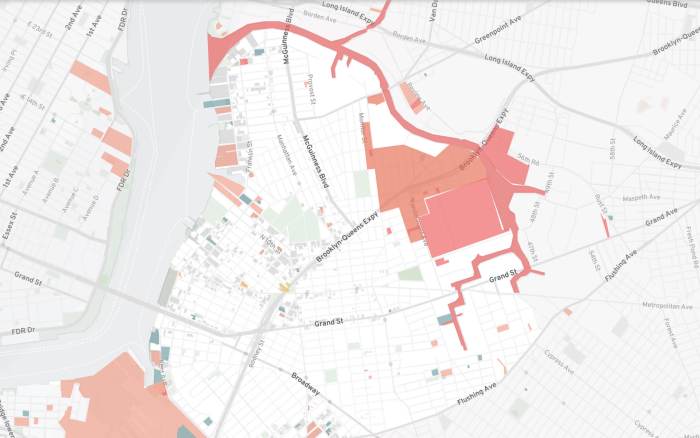

Dangerous concentrations of the chemicals have been found in the soil beneath and immediately surrounding NuHart, and floating on the surface of the groundwater there. While the DEC notes that people are unlikely to come in direct contact with the contaminated soil, gaseous VOCs can rise up into buildings in a process called “soil vapor intrusion” and be inhaled by occupants.

Hazardous chemicals can travel through soil and groundwater and end up below neighboring buildings.

“We did some sampling across Clay Street, to the north, we did find some vapor across the street to the north,” said Jane O’Connell, a DEC remediation engineer. “We did try to access some of the private properties across the street to do soil vapor intrusion testing, we were not successful at getting access to those properties.”

In 2019, DEC issued a “Record of Decision” for the state Superfund at NuHart West. That document lays out the steps necessary to clean the site, and requires any future owners of the lot to take responsibility for funding the roughly $30 million process. While NuHart East is not part of the Superfund, DEC did place a stipulation on the lot that future owners would need to remove leaking underground storage tanks and clean up the fuel and chemicals that had already soaked into the ground.

Brownfield cleanup

Demolition may begin as soon as March 15 at NuHart East, the Brownfield portion of the site. Asbestos abatement is done, Kadden said, and DEC has signed off on a “closure scope” necessitated by the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act, essentially approving the cleanup and giving Madison the green light to start taking down buildings. All that’s needed now is a demolition permit from the city, which Kadden anticipates receiving some time next week.

The below-grade remediation plan for NuHart East is currently being reviewed by the state and the city’s Office of Environmental Remediation. Once approved, excavation, further remediation, and construction can begin on the Brownfield site.

The company’s goal is to lay “foundational elements” at NuHart East and West by June 15 so the development will be eligible for the 421-a tax abatements.

The state Superfund

Cleanup at NuHart West, the state Superfund site, is going to take a little more time. Asbestos work is done, but crews are still working to decontaminate the manufacturing equipment that’s been sitting unused for nearly 20 years. According to the RCRA closure plan laid out late last year, the former factory was in need of extensive scrubbing before a single brick can be removed — storage tanks need to be emptied, cleaned, and removed, interim chemical-collection infrastructure temporarily decommissioned, and even the water used to hose down the building must be responsibly disposed of.

Still, Kadden said, that work should be done by and approved by the end of May, opening the door for demolition. After the structures have been torn down, Madison will submit their full remediation plan to DEC for approval under the ROD.

“The remedy includes full excavation to remove phthalate contamination on the Superfund portion of the site, as well as the TCE contaminated soil on the north central portion of the site” O’Connell explained. “Where it gets complicated is that the phthalate contamination does continue off-site under a public roadway, and that roadway has lots and lots of utilities in it, and it’s not amenable to a full excavation.”

Instead, a containment wall will be installed to keep chemicals from continuing to travel off-site, and as much of the phthalate-contaminated soil as can reasonably be reached beneath the road will be removed. How, exactly, that will happen has yet to be determined — it’s part of the ongoing design work.

Health concerns and monitoring

Neighbors are, of course, worried about the potential health effects of tearing down the buildings and digging into the contaminated soil — both during and after construction.

One longtime Greenpoint resident, Laura Hoffman, said she’s worried about the location of a school slated to be built across the street from NuHart when remediation is finished.

“I think it would be reckless to even consider it, even after the cleanup,” she said. “This neighborhood has a long history of being snookered by the environmental and health agencies. I just don’t believe that 100 percent safety has been achieved. My family has suffered enough over the years from this site, and I have no intention of letting any other family suffer without their knowledge.”

Councilmember Lincoln Restler echoed her concerns, and said his office has been working diligently with the School Construction Authority to find an alternative site.

“Northern Greenpoint needs a public school, and I’m fully and totally committed to helping to make that happen, but we need to do it at a site that is safe,” he said. “My commitment to this community is that we’re going to find a new school one way or another.”

Air quality monitoring has been ongoing throughout the remediation so far, and DEC will also implement the use of both stationary and roving air monitoring equipment once the Superfund cleanup begins in earnest. Consultants have also been testing the groundwater on a regular basis, O’Connell said, and she reassured residents that no groundwater in Brooklyn is used for drinking.

More mitigation measures will be developed and implemented before further cleanup and construction begins, O’Connell said. That could mean negative-pressure systems to keep odors contained, specially-lined truck beds to keep contaminated soil contained while it’s being removed from the site, and close monitoring of contractors and consultants working at NuHart to make sure they’re following procedures.

“We are going to have to make some kind of difficult decisions as a community,” said Lisa Bloodgood, interim executive director of North Brooklyn Neighbors. “But for now, we’re looking forward to — looking forward to is maybe not the right phrase — the demolition of the buildings. We do want to see a full remediation of this whole site, so the building’s got to come down for us to get there.”