A developer wants to cleanse heavily-polluted soil and groundwater at 34 Berry St. in Williamsburg through the state-subsidized Brownfield Cleanup Program — a decade after building a luxury complex and renting apartments to hundreds of tenants on top of the toxic grounds.

Manhattan landlord company Lcor in 2017 applied with the state’s Department of Environmental Conservation to remove toxic chemicals known as chlorinated solvents and petroleum from beneath its seven-story building at the corner of N. 12th Street, even though the building had already been occupied by tenants since 2009.

On Aug. 11, an engineer with the state agency presented the plan — scheduled for state approval in September — to local civic gurus, who lambasted the owner for allowing residents to live above the contaminated soil for so long.

“It seems insane that the developer has housed people on top of this site for 10 years without them clearly knowing what they’re living on top of and charging ridiculous amounts for rent and that they’re receiving a tax break from the state,” said Willis Elkins, a member of Community Board 1’s environmental protection committee at the virtual meeting.

Under the Brownfield Program, the developer shoulders the cost, but can recoup between 25 to 30 percent of their expenses through tax credits, according to DEC engineer Jane O’Connell, who delivered the presentation about the developer’s application to the board’s committee.

DEC spokesman Rodney Rivera declined to provide an estimate of the project’s cost, adding that the Department of Tax and Finance will report the actual price tag for the works after the cleanup is complete.

Lcor, which manages another building in Manhattan and several luxe properties in nine states along the East Coast, voluntarily applied for the cleanup program in 2017, O’Connell told the civic panel, after discovering the toxins underground, such as the synthetic compound 1,2-Dichloroethane (also known as 1,2-DCA), a chemical used to make plastic and vinyl products that can be carcinogenic, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

However, residents can rest safely, O’Connell assured the committee, due to the fact the building gets its water from the public supply, not the polluted groundwater, and because state inspectors could not detect any harmful chemicals that might have seeped through the building’s base in the form of vapors when they recently took air samples in the underground parking garage.

“We really did not see any indoor air impacts from the contaminants that we’re looking towards that are in the ground,” she said.

A leader of the committee said the fact that the chemicals didn’t come to light for years after residents moved in was troubling.

“It’s very disturbing that this arose over years after the building’s existence and tenants occupied the building,” said the committee’s co-chair Steve Chesler.

The community board routinely receives notices for Brownfield Program applications, according to Chesler, but this one stuck out to him because it came long after the housing was already built.

“In 99 percent of the cases, the sites are not even developed yet,” he said. “I’ve never heard of this happening after the fact and never to this extent.”

The pollution likely stems from the site’s past, when it used to house the pharmaceutical factory New York Quinine and Chemical Works from 1887 to 1951, before converting into an auto and truck repair shop during the second half of the 20th century, according to O’Connell.

Then-owners demolished the buildings in 2006 and the next year Lcor bought it for more than $16 million, property records show, before constructing the L-shaped apartment building between 2008-2009.

The recent toxic find is not the first dirty discovery on the lot. While excavating the site in February 2008, the developer also reported a petroleum spill from old oil tanks on the site to DEC, but inspectors might have overlooked the other poisonous chemicals at the time, according to O’Connell.

“They reported the spill and under the [DEC’s] Spill Program, we’re generally only looking for petroleum, we don’t do a full suite of analyses,” she said at the Community Board meeting. “For better or for worse, the initial [analysis] for volatile organics was limited to the petroleum seeds, and that’s why this may have gotten missed in that earlier investigation.”

That led the owners to install interim fixes in the following years, such as a recovery well to remove the oils and chemicals, as well as a vapor barrier and a pressure system that directs and vents polluted underground air pockets outside of the building. The new brownfield remediation will seek to expand these systems, while monitoring any uptick in toxic air quality levels, according to O’Connell.

At some point, engineering consultants for the developer made a broader analysis and found the chlorinated solvents in the groundwater, pollutants that were not from the oil spill and applied with DEC in 2017 for the cleanup program.

Lcor did not respond to a request for comment.

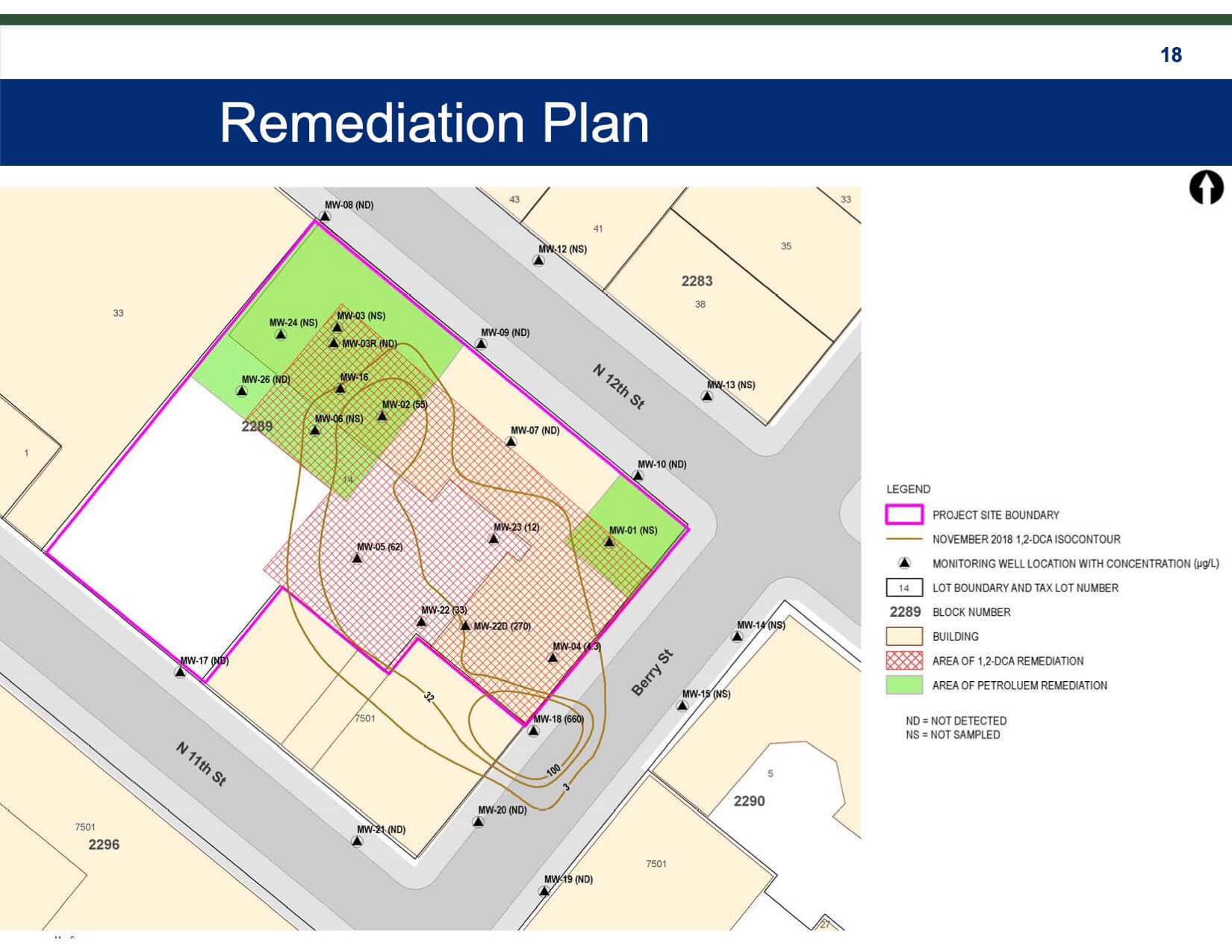

The initiative will remediate petroleum at the northeast and northwest corners of the lot, while cleaning the chlorinated solvents from the property’s center, according to officials.

The area of the petroleum cleanup is marked in green, and the sections for the chlorinated solvent remediation are marked with a red grid.NYS Department of Environmental Conservation

One resident said he’d never heard of the contamination underneath the building and said the owners should be legally required to disclose that kind of information to incoming tenants before they sign a lease.

“We never heard anything about the building’s past,” said Bryan Edwards, a one-year resident of the building. “It would be nice for them to have to mention that by law.”

Tenants did get an internal notification on Aug. 8 about work for brownfield project, but Edwards thought that was just some general maintenance work in the area and not a remediation for more than a century of historic pollution.

“I just thought it was some work being done in the general area, like utilities,” the resident said. “I didn’t really connect that with a problem under the building, I just thought it was area-wide.”

Meanwhile, the subterranean contamination has not dampened rent for any of the units. The development’s website greets prospective tenants with the slogan “Enjoy the life of Luxury,” and rents range from $2,225 for a studio to $4,795 for two-bedroom apartment.

There is also a private courtyard for residents with a vegetable garden and outdoor events, such as yoga and family barbecues, the building’s Facebook site shows.

The state plan for the site is open to public comment until Aug. 22 and officials expect to get it approved by September. A construction start date is still to be determined, according to O’Connell.

For more information on who to contact for comment, see DEC’s factsheet on the project here. Project documents are available online here or at Community Board 1’s offices at 435 Graham Ave., along with Brooklyn Public Library’s Leonard Branch at 81 Devoe St.