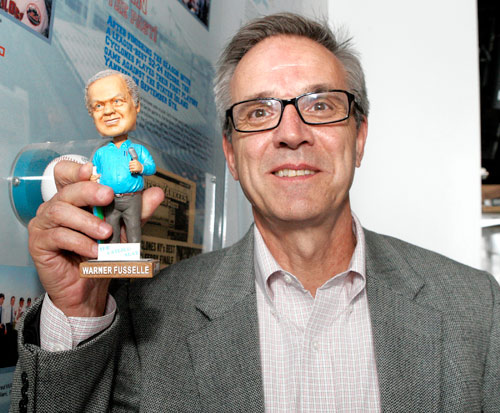

Dozens flocked to MCU Park last Friday to honor announcer Warner Fusselle, the voice of the Brooklyn Cyclones — a voice that was silenced on June 10 when the 68-year-old succumbed to a heart attack. We asked former Cyclones columnist Ed Shakespeare to tell us about working with the keeper of the Catbird Seat.

“Sitting in the Catbird Seat” is a venerable southern expression made famous by Red Barber, the Brooklyn Dodgers’ famed radio announcer. in the exquisite short story, “The Catbird Seat,” author James Thurber explains that Barber’s expression meant that you had the advantage, like a batter with a 3–0 count.

Warner Fusselle, the Brooklyn Cyclones’ radio announcer since the team’s inception in 2001, knew fellow southerner Red Barber and was a great admirer of his work. As a tribute to Barber and Brooklyn baseball history, Fusselle called his radio broadcast spot in the front of the Cyclones’ press box the “Catbird Seat.”

I met Warner on the first game in Cyclones’ history: June 19, 2001 in Jamestown, N.Y. Warner was upset. His tape recorder wasn’t working properly, it was about three hours before game time, and he was worried. Eventually, he fixed the tape recorder, but it was only the first of innumerable times that Warner, a perfectionist, was upset about things that could wind up impacting his broadcast.

I soon learned that he took his work very seriously. He was a warm and generous man, but he showed little tolerance for those who didn’t have a similar dedication. Over the years I saw him become incredulous as public address announcers would mispronounce names of Cyclones players after not taking Warner’s proffered pronunciation help, and I saw him become frustrated when student radio engineers at Kingsborough Community College’s WKRB — the Cyclones’ radio station for much of Warner’s time in the Catbird Seat — would show up late for work and delay his broadcasts.

Over the years we became friends. Warner invariably made his statistics and notes always available to me for my writing. I would often sit next to Warner in the Catbird Seat in Brooklyn, or at the away game Catbird Seat at venues around the New York–Penn League. I could hear his words in person and watch him work, as I sometimes informally helped him by getting some scoring information or spotting substitutions before they were announced over the public address system.

Warner kept meticulous hand-written statistics in a giant loose-leaf notebook that he lugged all over. He would spend hours after each game updating his stats.

And he absolutely hated computers, according toDave Campanaro, the former media relations director of the Cyclones.

“Warner hated what he called ‘machines,’ “ Campanaro said at a memorial service at MCU Park. “The way it worked was that when Warner’s personal stats and the computer’s stats disagreed, 10 times out of 10 Warner was right.”

Warner had a knack for coining nicknames that stuck. I loved it when he called me, “Bard” or sometimes “Brooklyn Baseball Bard.” He called his pal from his days at MLB Productions, John Cirillo, “Tex.”

Tex showed up at the memorial, where he opined on Warner’s talents.

“Warner was just as good as Mel Allen, Ernie Harwell, and Red Barber,” he said.

Long-time friend in sports, John Bacchia, said baseball was the perfect venue for the announcer.

“Warner lived his life by being where he wanted to be, doing what he wanted to do,” he said.

It wasn’t always easy, but Warner was able to live his life just the way he wanted.

For three hours every day from June to September, he was alive as a person could be — perched in the Catbird Seat, broadcasting baseball.

—Ed Shakespeare