The New York Times, which is working with Bruce Ratner to build a new Times headquarters in Manhattan, continues to trumpet its enthusiastic view of its partner’s Atlantic Yards mega-development. In a City section editorial that capped a string of upbeat “news” articles and unreported stories, Times writers seemed to be working off a Ratner press release. As a service to our readers, some of whom may also occasionally read the Times, we present a more nuanced view.

The Atlantic Yards Project

If there was ever a place in New York City to put a development that combines housing, businesses and a sports arena, it ought to be the Atlantic Yards site in Brooklyn, an underdeveloped [1] area near the borough’s downtown that has ready access to nine subway lines and the Long Island Rail Road. Yet the proposal by the developer, Bruce Ratner, has been controversial from the start, mainly because of opposition from area residents who fear it would change the character of their neighborhoods. [2]

After watching the project evolve [3] for the past few years, we feel — with a few caveats — that it deserves to go forward. The opportunities it presents, and the nearly 7,000 [4] apartment units it will provide a housing-starved city, outweigh the problems it would entail. These advantages have been repeated endlessly by Mr. Ratner, who is also The Times’s partner in building its new Manhattan headquarters. More than 2,200 of the apartment units would have rents targeted to low-, moderate- and middle-income [5] families. The Nets basketball team would bring major league sports back to Brooklyn. The buildings designed by Frank Gehry would add a sense of excitement to the entire area. And, when finished in 2016, the project will add substantially [6] to city and state tax revenues.

The developers have addressed [7] some of the community’s early objections, particularly worries about traffic. The most important promise involves improvements to the subway stations that would make it easier for riders to move from one line to another, or to the L.I.R.R. That should be a boon to local residents, who deserve to be rewarded for enduring what will be almost a decade of construction.

The plan also calls for changes in traffic light timing [8] and a reconfiguration of traffic flow around the arena; satellite parking for basketball fans; and a program that would combine game tickets with Metrocards [9] to keep as many fans as possible on the subways. Traffic will still be an issue [10] when the project is finished, but the developers are not obliged to hold the neighborhood harmless. Their job is to demonstrate that their buildings will not make a bad situation intolerable, and the promises made by Mr. Ratner and his associates seem like reasonable [11] responses to that challenge.

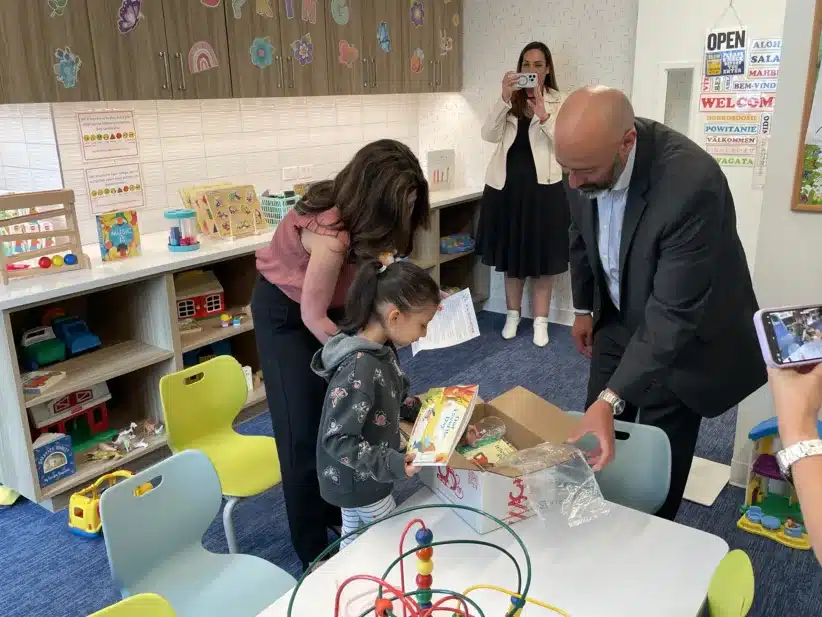

Community outreach [12] has been far better in the Atlantic Yards project than it was, say, in the now-defunct plans to build a Jets stadium in Midtown Manhattan. Mr. Ratner has worked hard to deal fairly with the property owners who would be displaced by the project, but he must also take care [13] to accommodate the rent-stabilized tenants who will have to leave.

A project of this size should have a meaningful public hearing process, so it is troubling that this one has not. It would help [14] if the 60-day public review period on the draft environmental impact statement released last month — at the height of summer — were extended another month, to late October.

And while the Ratner company will finance much of the project, taxpayers are still being asked to underwrite $200 million in direct city and state subsidies. Some $40 million, for example, is for land acquisition for the arena, which should be a developer expense. The project may require [15] the city to build more classrooms, expand sewer and water services and provide more police on game days. It is up to Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s administration to demand [16] from the developer every reasonable contribution to defray these extra expenses.

Finally, there is the matter of density [17] — the biggest, and most reasonable concern. At 8.7 million square feet, the project remains enormous, even after coming down 5 percent. [18] The non-profit Municipal Arts Society, a respected voice on urban design, came up with a still smaller version by applying city zoning standards, and parts of it are appealing, particularly in how it envisions more publicly accessible park space.

A more important issue is scale. The project would benefit if the square footage came down at least another 15 percent, which in turn would lighten the load on infrastructure, including the streets. Opponents of the plan have pressed for a more dramatic downscaling, pointing to the contrast with the surrounding, low-rise neighborhoods. But the planners are correct in seeing an opportunity to build something grander and doing it at the one place in the borough that can handle it. [19]

1) If it is underdeveloped, it is by design. The MTA, which owned the development rights, refused to consider other developers and ended up selling the rights to Ratner for $100 million — $114 million less than its value as appraised by the MTA itself, and likely hundreds of millions less than the site would fetch on the open market.

2) That’s a gross simplification. Some of the project’s neighbors do worry that their charming, low-rise communities will be overwhelmed by Ratner’s 16 skyscrapers, but concerns about the development extend beyond NIMBY-ism. A few points: Ratner’s track record is poor (just look at the barren Metrotech and the uninviting Atlantic Center mall); he received a sweetheart deal from the MTA for the Atlantic Yards site, as he did at Metrotech (where promised “trickle-down” prosperity, including jobs and fresh infrastructure throughout Downtown, never materialized; Atlantic Yards is skirting local public review; the state’s own analysis of it says that some of its impacts cannot be fixed.

3) This watch has not been apparent. Times coverage has been sporadic and generally Ratner-friendly.

4) It is actually 6,860, although Ratner has an option to drop it to 5,790. In any event, Ratner would be expected to repeat “endlessly” the “advantages” of his project; perhaps the Times could give equal attention to skeptics who repeat “endlessly” the project’s pitfalls.

5) The 2,250 “affordable” rental units would be distributed this way: 900 units to families of four earning less than $35,450; 450 units to families earning between $42,540 and $70,900; 900 units to families earning between $70,901 and $113,440. Ratner is receiving city, state and federal subsidies to create this affordable housing — so to the extent that affordable housing is desirable, keep in mind that Ratner’s not “giving” us any; the taxpayers will foot the bill.

6) Using Ratner’s own numbers, the city and state would each receive $35 million in tax revenue annually, a tiny — not a “substantial” — amount in a $37-billion city budget and a $112-billion state budget.

7) Traffic remains a significant community concern. How has it been “addressed”?

8) Light timing? Traffic experts say that this is not sufficient.

9) While Ratner has said he will create satellite parking lots and work with the MTA to give Nets fans subway discounts, it is not clear if people will use them in sufficient numbers to make any difference.

10) This contradicts an earlier claim that Ratner has “addressed” traffic concerns. After the project is complete, the intersection of Fourth and Flatbush avenues will only clear up after 10 pm and traffic will be congested all day long rather than only at rush hour at a number of intersections, according to state documents.

11) Reasonable? To whom? Residents of Manhattan? The very fact that Brooklynites are fighting the project indicates at the very least that many people do not believe Ratner’s responses have been reasonable.

12) Ratner’s community outreach has consisted mostly of signing a Community Benefits Agreement that pays signatories and forbids them from criticizing the project. Several signatory groups did not even exist prior to signing, an indication of their shallow roots in “the community.”

13) It is unclear whether he will. Some of Ratner’s rent-stabilized tenants are preparing to sue the state to block their eviction on grounds that their rights have been violated.

14) That’s too mild a word. City Council Speaker Christine Quinn, Attorney General Eliot Spitzer and all three of the affected Community Boards have demanded a longer review of the state’s 2,000-page draft environmental impact statement than the perfunctory 60 days.

15) “May require”? The state DEIS treats this as inevitable — and does not put a price tag on such government-paid-for amenities.

16) When? After the project is approved? The time to get the money is up front. The very fact that the city will have to clean up Ratner’s mess disproves an earlier Times assertion that the benefits outweigh the costs.

17) This superblock project would be the most-dense Census tract in the country!

18) Coming up, you mean. The five-percent reduction in scale announced earlier this year brought the project down to 8.659 million square feet — but that’s still a lot more than the 8 million square feet that the project originally contained when it was presented in 2003.

19) It’s nice that the Manhattan media knows what’s best for Brooklyn.